Clinical Description

Cranioectodermal dysplasia (CED) is a ciliopathy with significant involvement of the skeleton, ectoderm (teeth, hair, and nails), retina, kidneys, liver, lungs, and occasionally the brain. The current understanding of the CED phenotype is limited by the small number of well-described affected individuals reported and the even smaller number with a molecularly confirmed diagnosis.

To date, 44 individuals with biallelic pathogenic variants in one of the genes listed in Table 1 have been described clinically [Zaffanello et al 2006; Fry et al 2009; Gilissen et al 2010; Walczak-Sztulpa et al 2010; Arts et al 2011; Bredrup et al 2011; Bacino et al 2012; Hoffer et al 2013; Lin et al 2013; Alazami et al 2014; Tsurusaki et al 2014; Li et al 2015; Daoud et al 2016; Girisha et al 2016; Moosa et al 2016; Smith et al 2016; Antony et al 2017; Bayat et al 2017; Silveira et al 2017; Walczak-Sztulpa et al 2017; Xu et al 2017; Yoshikawa et al 2017; Ackah et al 2018; Córdova-Fletes et al 2018; Walczak-Sztulpa et al 2018; Walczak-Sztulpa et al 2020; Author, personal communication]. The following description of the phenotypic features associated with this condition is based on these reports.

Table 2.

Select Features of Cranioectodermal Dysplasia

View in own window

| Frequency | Features |

|---|

|

Frequent (>75%)

| Characteristic facial features (frontal bossing, low-set/simple ears, high forehead, telecanthus, epicanthal folds, full cheeks, everted lower lip) |

| Brachydactyly |

| Dolichocephaly & sagittal craniosynostosis |

| Shortening/bowing of proximal bones (most often humeri) |

| Short stature |

|

Common (50%-75%)

| Narrow thorax w/dysplastic ribs & pectus excavatum |

| Dental abnormalities (malformed, widely spaced, &/or hypodontia) |

| Sparse &/or thin hair |

| Nephronophthisis |

| Developmental delay (most often motor development) |

|

Less common (25%-50%)

| Joint laxity |

| Liver disease (hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, &/or hepatomegaly) |

| Syndactyly |

| Polydactyly |

| Abnormal nails |

| Skin laxity |

| Recurrent lung infections |

| Bilateral inguinal hernias |

|

Occasional to infrequent (<25%)

| Retinal dystrophy |

| Hip dysplasia |

| Cystic hygroma |

| Congenital heart defect |

| Intellectual disability |

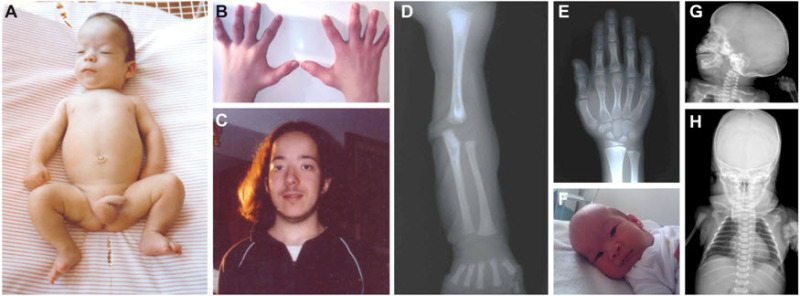

Characteristic facial features can be observed from birth and are evident in nearly all individuals with CED (see ), including frontal bossing, bitemporal narrowing, and a tall forehead; low-set, simple, and/or posteriorly rotated ears; telecanthus, epicanthal folds, and/or down-/upslanting palpebral fissures; full cheeks; micrognathia; everted lower lip; and anteverted nares.

Dolichocephaly (apparently increased anteroposterior length of the head compared to width) and frontal bossing are usually secondary to sagittal craniosynostosis, which is usually present at birth. Sib pairs may show discordance for sagittal craniosynostosis [Arts et al 2011, Bredrup et al 2011].

Skeletal findings

Hands and feet. Prenatal ultrasound may detect polydactyly during mid-gestation [

Konstantinidou et al 2009]. Neonates often have brachydactyly (with short middle and distal phalanges that may be abnormally shaped), postaxial polydactyly, and cutaneous syndactyly of fingers and toes (most frequently mild cutaneous syndactyly of second and third toes). Epiphyses of phalanges can have a normal appearance on radiograph or can be flattened or cone shaped [

Fry et al 2009]. Other findings of the hands and feet variably seen include fifth-finger clinodactyly, abnormal palmar creases, restricted finger flexion, osteoporosis, sandal gap, and/or triphalangeal hallux [

Gilissen et al 2010,

Bacino et al 2012,

Hoffer et al 2013,

Lin et al 2013].

Thorax. A narrow thorax with short dysplastic ribs is common, though not ubiquitous, and may be noted as early as mid-gestation; however, this finding was most commonly first noted at birth [

Lin et al 2013]. Pectus excavatum is often observed [

Hoffer et al 2013]. Rib deformities (e.g., short ribs, coat-hanger-shaped ribs) may normalize during childhood [

Bacino et al 2012].

Shortening (and bowing) of proximal long bones has been noted as early as 23 weeks' gestation. Upper limbs are often shorter compared to lower limbs; humeri are particularly affected. Long bones may display bowing, and epiphyses may be flattened and/or display metaphyseal flaring [

Bacino et al 2012,

Hoffer et al 2013,

Lin et al 2013].

Growth deficiency. At birth the length as related to gestational age may be within the normal range but can also be below the third centile. Infants may have growth deficiency with length below the third centile, but length may also be between the fifth and tenth centile [

Bacino et al 2012].

Ectodermal defects

Skin. Prenatal ultrasound may reveal mid-gestational nuchal webbing and skin thickening. Generalized skin laxity and redundant skin folds have been reported in infancy and thereafter. Skin folds have been found particularly at the neck, ankles, and wrists. Skin may be dry; hyperkeratosis has been reported [

Arts et al 2011,

Bredrup et al 2011,

Bacino et al 2012].

Hair. Most infants and young children with CED have sparse, fine hair. Hair may be hypopigmented with reduced diameter. Hair growth may also be affected [

Arts et al 2011,

Lin et al 2013]. In some instances, hair growth may normalize during childhood [

Konstantinidou et al 2009].

Kidney disease is due to nephronophthisis (tubulointerstitial nephritis). At least 60%-70% of persons with CED were reported to have renal insufficiency. Although end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) can be evident prenatally as poly/oligohydramnios and small cystic kidneys in the second trimester of pregnancy, the first signs of kidney disease are often evident in early childhood (age ~2 years) [Bacino et al 2012]. Initially reduced urinary concentrating ability leads to polyuria and polydipsia. Nocturnal enuresis may be evident. Hypertension, proteinuria, hematuria, and electrolyte imbalances usually develop later in the disease course as a result of renal insufficiency and filtration defects. In ten of 21 children kidney disease progressed to ESKD. Of note, this number may have increased over time as follow-up studies are limited. Most children developed ESKD between ages two and six years [Hoffer et al 2013, Lin et al 2013].

Renal ultrasound examination in infancy and early childhood usually shows normal-sized or small kidneys with increased echogenicity and poor corticomedullary differentiation [Lin et al 2013]. Renal biopsy shows interstitial fibrosis with focal inflammatory cell infiltrates, tubular atrophy, glomerulosclerosis, and occasional cysts [Obikane et al 2006, Konstantinidou et al 2009, Bredrup et al 2011, Lin et al 2013]. The latter features occur in advanced disease.

Liver findings range from hepatosplenomegaly without signs of progressive liver disease to extensive liver abnormalities including (recurrent) hyperbilirubinemia and cholestatic disease requiring hospitalization in the newborn period [Walczak-Sztulpa et al 2010, Bacino et al 2012]. Liver cirrhosis, severe cholestasis with bile duct proliferation, and acute cholangitis have been described in infants [Zaffanello et al 2006, Arts et al 2011, Bacino et al 2012, Lin et al 2013]. Liver cysts have been detected in children age three and four years [Hoffer et al 2013], but also as early as age ten months [Lin et al 2013]. Longitudinal data on liver disease are not available; however, the long-term prognosis with respect to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis is probably poor.

Eye findings include retinal dystrophy and nystagmus [Bredrup et al 2011, Lin et al 2013]. Nyctalopia (night blindness) is often evident in the first years of life [Bredrup et al 2011]. Abnormal scotopic and photopic electroretinograms have been reported as early as ages four to 11 years, while fundoscopy has revealed attenuated arteries and bone-spicule-shaped deposits as early as ages five to 11 years in some [Bredrup et al 2011]. The natural history of the retinal dystrophy remains to be reported; however, in overlapping ciliopathies such as Bardet-Biedl syndrome, night blindness usually progresses to legal blindness in young adults (see Bardet-Biedl Syndrome). A similar prognosis is to be expected in CED.

Other ophthalmologic findings include hyperopia, myopia, esotropia, myopic/hypermetropic astigmatism, and euryblepharon (excess horizontal eyelid length) [Konstantinidou et al 2009, Bredrup et al 2011, Hoffer et al 2013, Lin et al 2013].

Pulmonary. In infancy or early childhood, children with CED may experience life-threatening respiratory distress due to pulmonary hypoplasia and recurrent respiratory infections. Asthma and pneumothorax have also been reported [Bredrup et al 2011, Bacino et al 2012, Hoffer et al 2013]. Many children die of respiratory distress after birth or of pneumonia during early childhood [Tamai et al 2002]. Recurrent respiratory infections have been reported to diminish in frequency over time [Konstantinidou et al 2009].

Cardiac malformations have included patent ductus arteriosus and atrial and ventricular septal defects. Thickening of the mitral and tricuspid valves, ventricular hypertrophy/dilatation, and peripheral pulmonary stenosis have also been reported [Arts et al 2011, Bacino et al 2012]. Bacino et al [2012] reported one affected child in whom cardiac arrhythmia and atrial septal defect resolved at age three years.

Central nervous system. Although the majority of children develop normally, mild developmental delay is reported in some individuals [Hoffer et al 2013, Lin et al 2013]. Sitting unsupported may be delayed to nine to 15 months and walking to three years [Fry et al 2009, Bacino et al 2012, Hoffer et al 2013]. Delays in speech may vary from a few words at age 19 months to no words at age five years [Hoffer et al 2013]. No information is available on how affected individuals respond to speech and physical therapy. Cognitive and social abilities are usually normal but intellectual disability is diagnosed in some individuals [Fry et al 2009, Alazami et al 2014, Li et al 2015].

Brain imaging has revealed cortical atrophy, ventriculomegaly, large cisterna magna, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, focal microdysgenesis, enlarged extracerebral fluid spaces, large posterior fossa cyst, and Dandy-Walker malformation [Zannolli et al 2001, Fry et al 2009, Konstantinidou et al 2009, Bacino et al 2012, Hoffer et al 2013, Lin et al 2013, Girisha et al 2016, Walczak-Sztulpa et al 2020].

Other

Joint laxity can be observed from the neonatal period [

Fry et al 2009].

Life expectancy. Morbidity is high in individuals with CED and hospitalization may be frequent and/or extended [Bacino et al 2012]. Mortality rates are unclear, although 10/65 children with CED died before age seven years of respiratory failure [Levin et al 1977, Savill et al 1997, Tamai et al 2002], heart failure [Eke et al 1996, Savill et al 1997, Bacino et al 2012, Silveira et al 2017, Walczak-Sztulpa et al 2017], hypovolemic shock (as a result of coagulopathy) [Bacino et al 2012], or unknown causes [Lin et al 2013, Antony et al 2017]. This number could be higher as longitudinal data on the majority of individuals with CED are unavailable. At least three persons with CED survived into young adulthood (see Bredrup et al [2011] and ).