This chapter outlines the rigorous approach taken in the development of this guideline. An overview of the key contributing working groups and subsequent methodology of reaching a set of recommendations are outlined in detail.

Guideline Development Working Groups:

Three working groups were established and performed specific functions in the development of the guideline. These included the WHO Guideline Steering Group, the Guideline Development Group and the External Review Group. They were joined by the United Nations and external observers at the Guideline Development Group meeting in January 2019.

Topic Areas for New Recommendations and Good Practice Statements:

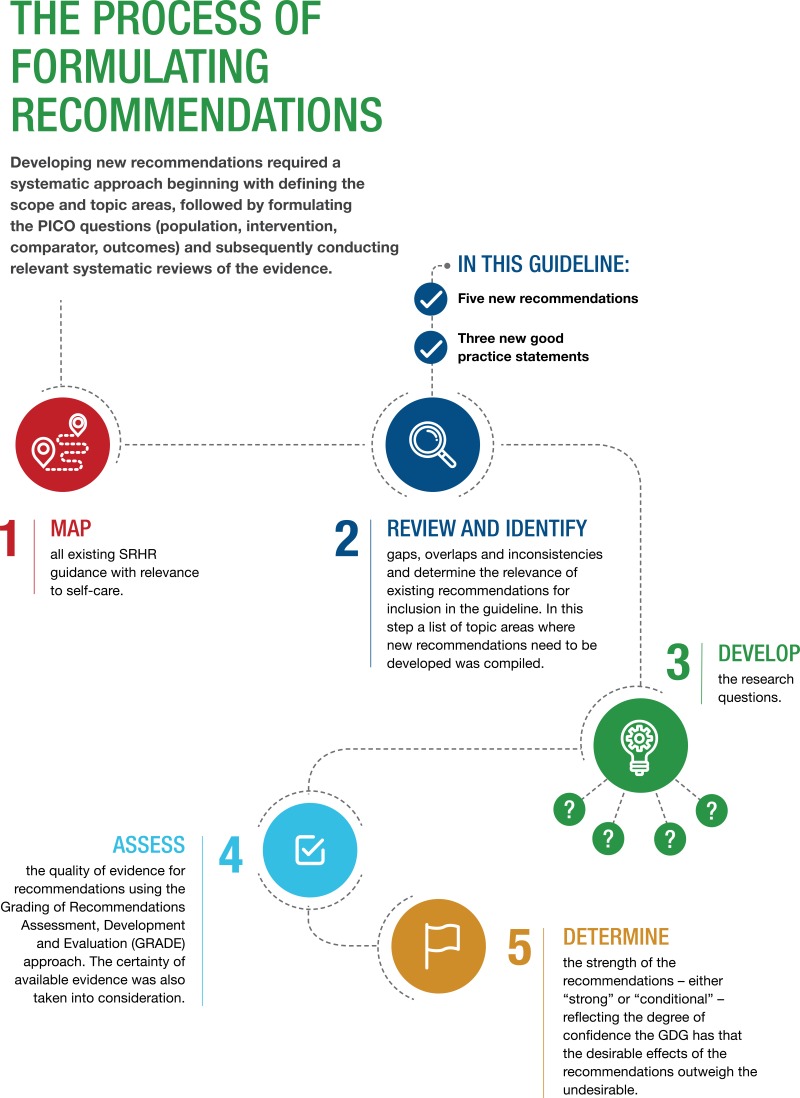

This guideline compiles new, adapted and existing recommendations and good practice statements on self-care. Five new recommendations and three new good practice statements are presented.

Compilation and Presentation of the Guideline:

The bulk of this chapter focuses on describing the knowledge gaps identified by the Guideline Development Group that need to be addressed through further primary research. Questions to address these gaps are presented by topic and by GRADE domain.

“Members of the working groups were selected so as to ensure a range of expertise and experience, including appropriate representation in terms of geography and gender.”

The WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research led the development of this consolidated guideline, following WHO procedures and reporting standards laid out in the WHO handbook for guideline development (1).

3.1. Guideline Development Working Groups

The Department set up three working groups to perform specific guideline development functions (): the WHO Guideline Steering Group (SG), the Guideline Development Group (GDG) and the External Review Group (ERG). Members of the groups were selected so as to ensure a range of expertise and experience, including appropriate representation in terms of geography and gender. The three working groups are described in the following subsections and the names and institutional affiliations of the participants of each group are listed in Annex 1.

3.1.1. The WHO Guideline Steering Group (SG)

Due to the nature of the guideline, the SG included representation and expertise in sexual and reproductive health (SRHR), including the main fields of family planning, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), maternal health, sexual health and abortion. In addition, gender, ethics, social accountability and human rights expertise ensured that key principles for building a strong enabling environment, particularly for vulnerable populations, were adequately reflected. Finally, regional and country WHO representation provided expert perspectives – from the very start of the normative guideline development process – on the practicalities of implementation and uptake of the recommendations and good practice statements in the various regions.

The SG, chaired by the Department of Reproductive Health and Research, led the guideline development process. The members drafted the initial scope of the guideline; identified and drafted the priority questions in PICO format (population, intervention, comparator, outcome); identified individuals to participate as guideline methodologist and as members of the systematic review teams, the GDG and the ERG (see below). The SG did not determine or agree on the final recommendations as this was the role of the GDG. The SG also finalized and published the guideline document and will oversee dissemination of the guideline and be involved in the development of implementation tools.

Guideline Development Expert Working Groups and Observers.

3.1.2. The Guideline Development Group (GDG)

The SG identified and invited external (non-WHO) experts to be part of the GDG, with expertise covering the same technical areas of work as the SG, including researchers, policy-makers and programme managers, and including young health professionals. All WHO regions were represented, with gender balance.

The GDG members were involved in reviewing and finalizing key PICO questions and reviewing evidence summaries from the commissioned systematic reviews. They were also responsible for formulating new WHO recommendations (REC) and good practice statements (GPS) at the GDG meeting (14–16 January 2019, in Montreux, Switzerland), as well as for achieving consensus on the final content of the guideline document.

3.1.3. The External Review Group (ERG)

The ERG members, who were identified and invited to participate by the SG, included peer reviewers with a broad range of expertise in issues related to SRHR. They included clinicians, researchers, policy-makers and programme managers, as well as representatives of civil society (including youth), and young health professionals. The ERG members were asked to review and comment on a version of the guideline that was shared with them after it had been reviewed and revised by the SG and the GDG. The purpose of this step was to provide technical feedback, identify factual errors, comment on the clarity of the language, and provide input on considerations related to implementation, adaptation and contextual issues. The group ensured that the guideline decision-making processes had considered and incorporated the contextual values and preferences of persons affected by the recommendations. It was not within the ERG’s remit to change the recommendations that had been formulated by the GDG.

3.2. Additional Key Contributors

3.2.1. External partners

In accordance with guidance in the WHO handbook for guideline development (1), donors, partners and representatives of United Nations agencies were invited to attend the GDG meeting in January 2019 as observers with no role in determining the recommendations.

United Nations partners include:

The Defeat-NCD Partnership

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

World Bank.

External partners represented the following agencies:

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

International Self-Care Foundation

PATH

Population Council

Population Services International (PSI)

White Ribbon Alliance.

3.3. Declaration of Interests by External Contributors

In accordance with the WHO handbook for guideline development (1), all proposed GDG and ERG members were requested to submit a one-page curriculum vitae and a signed WHO Declaration of Interest (DoI) form. Two members of the WHO Guideline Steering Group (SG) independently reviewed the DoI forms. The reviewers considered all possible conflicts of interest based on the latest guidance from the WHO Guidelines Review Committee (GRC), including placing a particular focus on possible financial or personal non-financial conflicts (e.g. academic contributions), as well as relationships with institutions producing self-care products.

Subsequently, biographical information for all GDG members deemed to not have significant conflicts of interest (i.e. conflicts which precluded their participation in the GDG) were posted on the WHO website for public comment 1–16 November 2018.1 GDG members were confirmed once this process was completed.

On confirmation of their eligibility to participate, all GDG and ERG experts were instructed to notify the responsible technical officer of any change in relevant interests during the guideline development process and to update and review any conflicts of interest accordingly. All GDG

Areas with New Recommendations and Good Practice Statements Developed for the Guideline.

members were required to verbally declare any conflict of interest at the start of the GDG meeting and subsequently before submitting comments on a draft version of the guideline. Interests were declared openly at the meeting so that all fellow GDG members were made aware of any interests that existed within the group. There were no cases of conflicts of interest that warranted management of DoI or assessment of potential conflicts of interest by the WHO Office of Compliance, Risk Management and Ethics.

No member had a financial conflict of interest. One GDG member had an intellectual conflict of interest, given their participation as a co-author on one of the systematic reviews, and recused themselves from the discussion and decision-making for the related PICO question. In addition, the GDG co-chairs did not present any conflicts of interest. A summary of the DoI statements and information on how conflicts of interest were managed are included in Annex 5.

The co-chairs had equal responsibilities and complementary expertise and perspectives, came from two different WHO regions, presented gender balance, and possessed areas of expertise relevant for this guideline. Both also had experience in consensus-based processes. At the start of the GDG meeting, the choice of two co-chairs was presented to the GDG by the SG members, and agreement sought and obtained from the GDG members on the selection of the co-chairs.

3.4. Defining the Scope and Topic Areas for New Recommendations and Good Practice Statements

Working within the general scope of the guideline as presented in Chapter 1, section 1.7, while also considering the intended users of the self-care interventions and the intention of addressing both an enabling environment and specific relevant health interventions, the SG first mapped all existing WHO SRHR guidance with relevance for self-care. The SG then reviewed these and other materials to identify gaps, overlaps and inconsistencies and to determine the relevance of existing recommendations for inclusion in this consolidated guideline. The SG identified the following topic areas where new recommendations needed to be developed for this guideline (): self-administration of injectable contraception; over-the-counter (OTC) provision of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs); use of home-based ovulation predictor kits (OPKs) for fertility management; HPV self-sampling (HPVSS) for cervical cancer screening; and self-collection of samples (SCS) for sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing. In addition, they identified the follow areas where new good practice statements were needed (): the life-course approach to SRHR; the use of digital health interventions to support the use of self-care interventions; and support for self-care interventions in humanitarian settings.

3.5. Review of the Evidence and Formulation of Recommendations

3.5.1. Defining and reviewing priority questions

Development of the new recommendations on health interventions (RECs 10, 11, 12, 21 and 22; see Table 1 in the Executive summary, and Chapter 4) began with formulating the PICO questions and subsequently conducting relevant systematic reviews of the evidence. The five PICO questions for the new recommendations were as follows:

For individuals of reproductive age using injectable contraception, should self-administration be made available as an additional approach to deliver injectable contraception? (

RECOMMENDATION 10)

For individuals using oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), should OCPs be made available over-the-counter (OTC), i.e. without a prescription? (

RECOMMENDATION 11)

For individuals attempting to become pregnant, should home-based ovulation predictor kits (OPKs) be made available as an additional approach for fertility management? (

RECOMMENDATION 12)

For individuals aged 30–60 years, should human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling be offered as an additional approach to sampling in cervical cancer screening services? (

RECOMMENDATION 21)

For individuals using sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing services, should self-collection of samples (SCS) be offered as an additional approach to deliver STI testing services? (

RECOMMENDATIONS 22a AND

22b)

The full details on the population, intervention, comparator and outcomes for each of the five PICO questions are presented in Annex 6.

A list of all reviews conducted for the development of this guideline – starting with the five systematic reviews on the PICO questions listed above – is presented in Annex 7. Please refer to the published systematic reviews for information about the methods used, including search strategies.

Among these reviews were literature reviews of the values and preferences of end-users/potential end-users and health-care providers relating to the self-care interventions addressed by each of the five PICO questions. The literature reviews on values and preferences for the OTC OCPs and for home-based OPKs were included within the same publications as the systematic reviews of the effectiveness of these self-care interventions (2, 3), and the methods for these reviews are therefore provided in those publications (see Annex 7). The literature reviews for the other three self-care interventions have not been published separately, but a summary of the findings of all five of these reviews for each of the self-care interventions is included at the end of each section where the five new recommendations are presented, in Chapter 4 (see sections 4.2.1 and 4.4.1). See also Chapter 1, section 1.9, about the Global Values and Preferences Survey (GVPS) on self-care interventions for SRHR.

3.5.2. Assessment of the quality of the evidence for recommendations

In accordance with the WHO guideline development process, when formulating the recommendations, the GDG members’ deliberations were informed by the quality and certainty of the available evidence. WHO has adopted the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to recommendation development (1). Regarding the application of GRADE, as explained by Balshem et al., “In the context of a systematic review, the ratings of the quality of evidence reflect the extent of our confidence that the estimates of the effect are correct. In the context of making recommendations, the quality ratings reflect the extent of our confidence that the estimates of an effect are adequate to support a particular decision or recommendation” (4). The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality of evidence, which should be interpreted as detailed in .

The GRADE approach to appraising the quality of quantitative evidence was used for all the critical outcomes identified as part of the PICO questions (see Annex 6). Critical outcomes are those outcomes that are considered most important to individuals who are likely to be directly affected by the guidelines. The rating of the outcomes was identified a priori by the systematic review teams in consultation with the SG. Following completion of each

Description of the Four Grade Levels of Quality of Evidence.

systematic review, a GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) table was prepared for each quantitative critical outcome arising from each PICO. The GRADE tables are presented in the Web annex.

23.5.3. Determining the strength of a recommendation

A recommendation for an intervention indicates that it should be implemented; a recommendation against an intervention indicates that it should not be implemented. The strength of a recommendation – assigned as either “strong” or “conditional” – reflects the degree of confidence the GDG has that the desirable effects of the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects for a positive recommendation, or the reverse (that the undesirable effects outweigh the desirable effects) if the GDG is recommending against the intervention.

Desirable effects (i.e. benefits) may include beneficial health outcomes for individuals (e.g. reduced morbidity and mortality); reduced burden and/or costs for the individual, the family, the community, the programme and/or the health system; ease of implementation (feasibility); and improved equity. Undesirable effects (i.e. harms) may include adverse health outcomes for individuals (e.g. increased morbidity and mortality); and increased burden and/or costs for the individual, the family, the community, the programme and/or the health system. The burden and/or costs may include, for example, the resource use and cost implications of implementing the recommendations – which clients, health-care providers or programmes would have to bear – as well as potential legal ramifications where certain practices are criminalized.

A strong recommendation (for or against the intervention) is one for which there is confidence that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation clearly outweigh the undesirable effects. The higher the quality of the scientific evidence base, the more likely that a strong recommendation can be made. A conditional recommendation is one for which the quality of the scientific evidence base may be low or may apply only to specific groups or settings; or a conditional recommendation may be assigned in cases where the GDG concludes that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects or are closely balanced, but the GDG is not confident about these tradeoffs in all situations.

If implemented, an intervention that received a conditional recommendation (i.e. recommended in specific contexts, or recommended only in the context of rigorous research) should only be implemented in the appropriate context and should be monitored closely and evaluated rigorously. Further research will be required to address the uncertainties, and this may provide new evidence that may change the overall assessment of the quality of the evidence.

The values and preferences of the end-users (or potential end-users) in relation to the intervention and the acceptability to health-care providers of implementing the intervention, as well as consideration of the relevant resource use, feasibility and equity issues, all contribute to determining the strength of a recommendation (see ). For this guideline, specific attention was also focused on the need for an enabling environment for implementation of interventions (see Chapter 2), and the GDG was asked to consider the human rights implications (both positive and negative) of each recommendation.

3.6. Decision-Making by the GDG during Guideline Development

The GDG members were guided by the clear protocol in the WHO handbook for guideline development (1). Ideally all decisions would be made by consensus. However, at the beginning of the meeting the GDG members agreed that if any decisions required a vote, the vote would need to be carried by a 60% majority.

The GDG reviewed the evidence contained in the systematic reviews and in the GRADE EtD tables, and discussed the topics under consideration, facilitated by the guideline methodologist. The GDG meeting was designed to allow participants to consider and judge each of the GRADE domains (see ) and formulate the recommendations through a process of group discussion, engagement and revision. To gain an initial indication of GDG members’ views on the direction of each recommendation (to recommend for or against an intervention), and on the strength of each recommendation (strong or conditional) as drafted, the methodologist sometimes asked participants to raise their hands in support of each separate option. This was not a formal vote, but a decision-making aid to allow the methodologist and co-chairs to gauge the distribution of opinion and subsequently work towards consensus through further discussion. The final wording of each recommendation, including an indication of its direction and strength, was confirmed by consensus among all GDG members. In one instance, a GDG member asked for their concerns regarding a specific decision to be noted in the guideline, but did not oppose the consensus agreement. The judgements made by the GDG related to each recommendation are noted in Annex 8.

Grade Domains Considered when Assessing the Strength of Recommendations.

3.7. Compilation and Presentation of Guideline Content

Following the GDG meeting, members of the WHO Guideline Steering Group (SG) prepared a draft of the full guideline document, including revisions to the recommendations to accurately reflect the deliberations and decisions of the GDG members.

The draft guideline was then sent electronically to the GDG members for further comment, and their feedback was integrated into the document before it was sent to the External Review Group (ERG) members electronically for their input. The SG then carefully evaluated the input of the ERG members for inclusion in the guideline document and the revised version was again shared electronically with the GDG members for information. Any further modifications made to the guideline by the SG were limited to correction of factual errors and improvement in language to address any lack of clarity. The revised version was then submitted to the WHO Guidelines Review Committee (GRC) for approval and minor requested revisions were made before final copyediting and publication.

This guideline presents WHO recommendations that have been newly developed and published for the first time in this guideline in 2019 (indicated by the label of “NEW” after the recommendation number) as well as existing recommendations that have been previously published in other WHO guidelines that applied the GRADE approach (all the recommendations not labelled as “NEW”), as well as new, adapted and existing good practice statements (again the former are labelled as “NEW”).

The recommendations – numbered and labelled as “REC” in Table 1 in the Executive summary, and presented in detail in Chapter 4 – relate to health interventions, and are presented in five sections which reflect the priority areas of the 2004 WHO Global Reproductive Health Strategy (sections 4.1–4.5). In Chapter 4, new and existing recommendations are presented

Presentation of Recommendations and Good Practice Statements in the Guideline.

in boxes, including information about the strength of each recommendation and the certainty of the evidence on which it is based (assessed using the GRADE method, as described in

section 3.5), followed by a list of remarks (if any), including key considerations for implementation highlighted by the GDG. For existing recommendations, the remarks are limited to the title, year of publication and the web link for the original source guideline, providing easy access to further information.

For each of the new recommendations, which address new topic areas or replace previous recommendations, additional information is presented in the following order after the box presenting the new recommendation(s):

background information about the intervention;

a summary of evidence and considerations of the GDG, including results relating to the effectiveness of the intervention (benefits and risks), and explanations about the certainty of the evidence and the strength the recommendation, in addition to information on resource use, feasibility and equity implications, and acceptability of the intervention to end-users and health-care providers (i.e. their values and preferences).

For existing recommendations, additional information after the box presenting the recommendations is limited to some background information about the intervention.

The good practice statements – numbered and labelled as “GPS” and presented in detail in Chapter 5 – apply to the implementation and programmatic considerations as well as the creation and maintenance of an enabling environment required for successful achievement of optimal SRHR. In Chapter 5, the new, adapted and existing good practice statements are presented in boxes. For existing and adapted good practice statements, the boxes include remarks (if any) on key implementation considerations; in most cases, the remarks are limited to the title, year of publication and the web link for the original source guideline, providing easy access to further information.

For each new good practice statement, additional information is presented in the following order after the box presenting the new good practice statement(s):

background information;

barriers to SRHR;

components of an enabling environment that will address the barriers and support SRHR; and

a summary of evidence and considerations of the GDG, including any additional implementation considerations, to support optimal understanding, implementation and outcomes.

For adapted and existing good practice statements, additional information after the box presenting the statements is limited to some background information about the relevant practice.

In addition, in Chapter 5, for each topic section, one or more case study is included in a box at the end of the section. See for a summary of the information presented in Chapters 4 and 5.

Chapter 6 presents a list of research gaps and priorities, as identified by the GDG, which require further study.

Chapter 7 describes the plans for dissemination, application, monitoring and evaluation, and updating of the guideline and recommendations.

Evidence derived from the five systematic reviews in support of the five new recommendations (see Annex 7) was summarized in GRADE tables to provide the evidence base on effectiveness that informed the new recommendations in this guideline. These GRADE tables are presented separately in the Web annex.

References for Chapter 3

- 1.

- 2.

Kennedy

CE, Yeh

PT, Gonsalves

L, Jafri

H, Gaffield

ML, Kiarie

J, Narasimhan

M. Should oral contraceptive pills be available without a prescription? A systematic review of over-the-counter and pharmacy access availability. BMJ Glob Health. 2019 (in press). [

PMC free article: PMC6606062] [

PubMed: 31321085]

- 3.

Yeh

PT, Kennedy

CE, van der Poel

S, Matsaseng

T, Bernard

LJ, Narasimhan

M. Should home-based ovulation predictor kits be offered as an additional approach for fertility management for women and couples desiring pregnancy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001403. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001403. [

PMC free article: PMC6509595] [

PubMed: 31139458] [

CrossRef]

- 4.

Balshem

H, Helfand

M, Schünemann

HJ, Oxman

AD, Kunz

R, Brozek

J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–6. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [

PubMed: 21208779] [

CrossRef]

- 5.

Schünemann

H, Brozek

J, Guyatt

G, Oxman

A. GRADE handbook: handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group; 2013 (

http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html, accessed 30 April 2019).