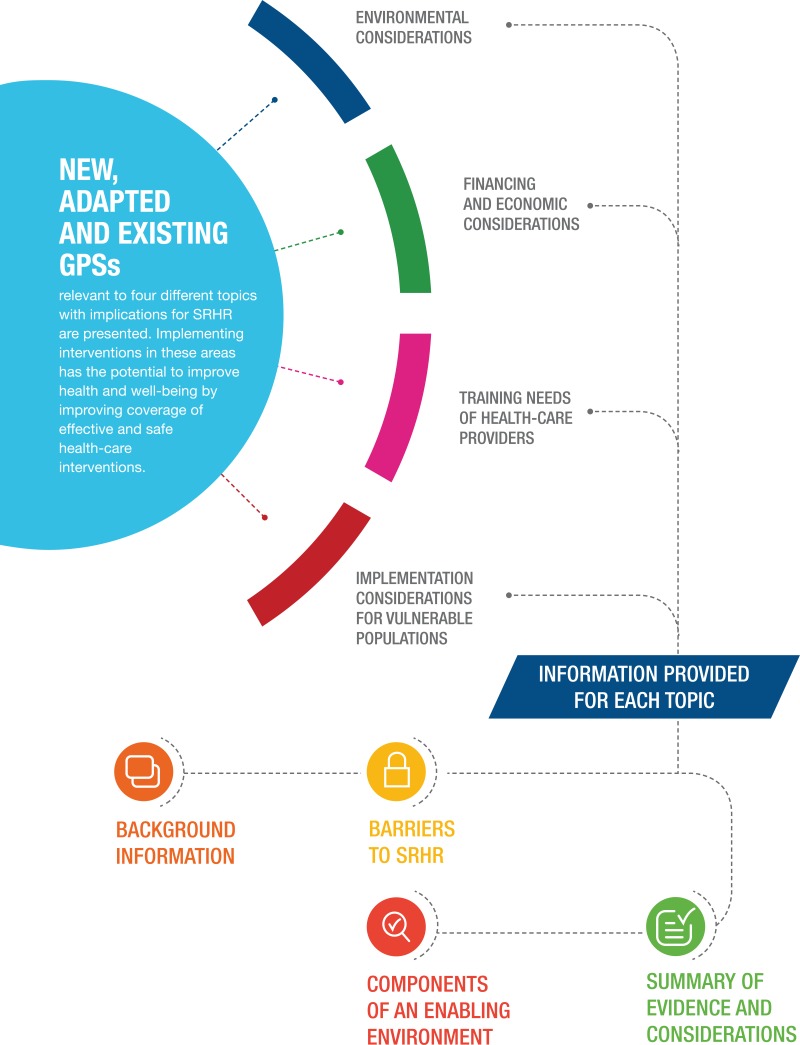

This chapter acknowledges the impact that changes in self-care practices may have upon an individual and society. Good practice statements (GPS) are presented on four different topics which have implications for the implementation of self-care interventions for SRHR.

Environmental Considerations:

Roughly a quarter of all human disease and death in the world can be attributed to environmental factors.

Financing and Economic Considerations:

Self-care interventions present a critical opportunity for health systems to support the pillars of universal health coverage, namely equitable access, efficient delivery of quality health interventions, and financial protection.

Training Needs of Healthcare Providers:

In order for self-care interventions to be successfully accessed and used, learning, communication and intersectoral collaboration are needed.

Implementation Considerations for Vulnerable Populations:

The needs and rights of vulnerable populations are highlighted in this guideline as certain situations or contexts, due to socioeconomic factors, disabilities, legal status and unequal power dynamics adversely affect health outcomes for populations who cannot access quality health care.

“Interventions that promote self-care and are promoted or used by the ‘professional’ sector must be implemented in a manner that respects people’s needs and rights.”

5.1. Overview

Many everyday health problems are treated at home and in communities, increasingly with modern pharmaceuticals obtained from pharmacies, stores and markets (1). Sometimes people combine remedies from traditional (folk) medicine and from modern medicine, learning from friends, family, the Internet, vendors and professionals, and applying the therapies themselves, especially if they are constrained by cost and/or distance (2). As Kleinman defined it, this is the “popular” health care sector. However, with the growth of virtual self-help communities and access to a vast range of information online, the division between lay and expert knowledge is becoming increasingly blurred (3).

Given the popularity of self-care in the “popular” sector, interventions that promote self-care and are promoted or used by the “professional” sector must be implemented in a manner that respects people’s needs and rights (Figure 5.1).

Acknowledging and understanding how existing practices of self-care are embedded in people’s lives and in the settings where they live is an important first step when developing, promoting or implementing self-care interventions. Furthermore, building partnerships between user-led and community-led platforms and health systems around self-care interventions is a promising approach to ensure correct and accelerated implementation of interventions that have the potential to improve health and well-being by improving coverage of effective and safe health-care interventions (5).

This chapter presents new and existing good practice statements (labelled as “GPS”) relevant to four different topics that have implications for the implementation of self-care interventions for SRHR: environmental considerations; financing and economic considerations; training of health-care providers; and implementation considerations for vulnerable populations. Background information relevant to each topic is provided, as well as a review of the evidence and the barriers and enabling factors relevant to each of the new good practice statements developed for this guideline. For each of the existing good practice statements adapted for this guideline from other WHO sources, a weblink is provided to the source document for further information.

FIGURE 5.1

Kleinman’s Health Care Sectors. Source: adapted from Kleinman, 1978 (4).

5.2. Environmental Considerations

5.2.1. Adapted good practice statements on management of waste from self-care products

i. Background

Roughly a quarter of all human disease and death in the world can be attributed to environmental factors, including unsafe drinking water, poor sanitation and hygiene, indoor and outdoor air pollution, workplace hazards, industrial accidents, occupational injuries, automobile accidents, poor land-use practices and poor natural resource management (7). More than one quarter of the 6.6 million annual deaths to children under 5 years old are associated with environment-related causes and conditions (8). Compared with high-income countries, environmental health factors play a significantly larger role in low-income countries, where water and sanitation, along with indoor and outdoor air pollution, make major contributions to mortality (8).

As we reduce dependence on hospital-based systems and increase our reliance on people-centred/user-controlled interventions, an increase in waste disposal of self-care products by the general population is inevitable. For self-care interventions to be sustainable, a change in patterns of health-care consumption, more sustainable production methods of health-care commodities, and improved waste management techniques will be required. While data are scarce and research is limited – particularly in resource-constrained settings – the rising popularity and availability of self-care interventions offers a valuable opportunity to take steps to responsibly manage the environmental impacts.

Worldwide, an estimated 16 billion injections are administered every year. Not all needles and syringes are disposed of safely, creating a risk of injury and infection, and opportunities for reuse (9). In 2010, unsafe injections using contaminated supplies were still responsible for as many as 33 800 new HIV infections, 1.7 million hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections and 315 000 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections. Additional hazards occur from scavenging at unsecured waste disposal sites and during the handling and manual sorting of hazardous waste from health-care facilities. These practices are common in many regions of the world, especially in low- and middle-income countries. The waste handlers are at immediate risk of needle-stick injuries and exposure to toxic or infectious materials. In 2015, a joint WHO–UNICEF assessment found that 58% of sampled facilities from 24 countries had adequate systems in place for the safe disposal of health-care waste (10).

In many parts of the world, the rising incidence of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases is the major driving factor for the growth of the market for self-care medical devices. Preference for home-based monitoring of these diseases has led to a reduction in the frequency of visits to clinics and hospitals, and an increase in the uptake of self-care medical devices. Growing awareness about health and health care has also triggered the demand for self-care medical devices and this is expected to grow further.

To ensure that the rise of self-care products does not have unintended harmful effects on human health and the environment, the procurement of environmentally friendly (“green”) goods is important, while ensuring that clinical outcomes remain key. WHO subscribes to a “green” procurement policy, and seeks to procure goods and services that lessen the burden on the environment in their production, use and final disposal, whenever possible and economical (11).

To effect “green” procurement, WHO supports the “4R” strategy to:

- re-think the requirements to reduce environmental impact

- reduce material consumption

- recycle materials/waste and

- reduce energy consumption (11).

Before finalizing the procurement of goods and/or services, the environmental concerns must be considered, including energy consumption, toxicity, ozone depletion and radiation.

Environmentally preferable purchasing (EPP) refers to the purchase of the least damaging products and services, in terms of environmental impact. At its simplest, EPP may lead to the purchase of recycled paper, through to more sophisticated measures such as the selection of medical equipment based on an assessment of the environmental impact of the equipment from manufacture to final disposal – known as “life-cycle thinking” (12).

WHO supports the safe and sustainable management of wastes from health-care activities (12, 13).

As stated in a subsequent key policy paper in 2007:

In keeping with these core principles, that paper made a series of specific recommendations aimed at governments, donors/partners, nongovernmental organizations, the private sector and all concerned institutions and organizations: these are presented in Box 5.1 (14). The case study in Box 5.2 gives some information on progress that has already been achieved in this area.

5.3. Financing and Economic Considerations

5.3.1. Adapted good practice statements on economic considerations of self-care

i. Background

In addition to increased user autonomy and engagement, self-care interventions present a critical opportunity for health systems to support the pillars of universal health coverage (UHC), namely equitable access, efficient delivery of quality health interventions, and financial protection (Figure 5.2) (18, 19). They could enhance the efficiency of health care delivery by co-opting users as lay health workers, thereby increasing access to essential services.

They could also increase the uptake of preventive services, and improve adherence to treatment, thereby reducing downstream complications and health care utilization (20). Vulnerable and marginalized populations could be given new routes of access to SRHR services that they would otherwise not access through health-care providers due to stigma, discrimination, distance and/or cost. However, there are also potential risks of introducing or further exacerbating vulnerabilities through the abrogation of government responsibility for quality health services. Moreover, shifting control to individuals may inadvertently shift the financial burden and increase out-of-pocket expenditures.

FIGURE 5.2

Self-Care within the Health-Care Pyramid. Source: adapted from WHO, 2003 (21).

Access for all to essential health services of high quality is the cornerstone of UHC. However, since economic considerations are particularly important for vulnerable populations who do not frequently engage with the health system, it will be critical to assess the value for money of these interventions from a societal perspective that factors in the costs (and potential cost-savings) for individuals (25).

Self-care interventions can also help to contain some health system costs, by co-opting users as their own health-care providers and by taking care outside of health-care facilities, provided that the interventions largely maintain diagnostic accuracy, uptake and quality of care. Moreover, for most self-care interventions to remain safe and effective, the involvement of health-care providers is required along the continuum of care – from the provision of information about self-care interventions, to outreach to promote linkages to care where appropriate – which may constrain the cost-savings that can be generated for the health system, especially in the early stages of adoption of new technologies. Importantly, for these interventions to improve overall access for users, health systems will need to be able to identify those users requiring different levels of support. The availability of self-care alongside facility-based health services may even contribute to more efficient health systems with better health outcomes, not least by including self-care as part of an integrated health system, allowing those who can manage their own health care to do so, while focusing health system resources on those who most need help.

When considering the financing of these interventions, a distinction should be made between entirely self-initiated/self-administered tools without health-care provider involvement, and those that are integrated within health-care provision. Self-care interventions must be promoted as part of a coherent health system, reinforced with health system support where required. The health system remains accountable for patient outcomes linked to the use of these interventions and should closely monitor their economic and financial implications for households and governments – otherwise, the wide use of self-care interventions may promote fragmented, consumerist approaches to health care and undermine integrated person-centred care.

5.4. Training Needs of Health-Care Providers

5.4.1. Existing good practice statement on the promotion of self-care interventions by the health workforce

i. Background

Workforce 2030 is WHO’s global strategy on human resources for health (29) and, together with the report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth (30), both published in 2016, it describes an escalating mismatch between supply, demand and population need for health workers. The strategy proposes the reorientation of health systems towards population need (rather than around professional clinical specialties), and plans the scale-up of competency-based professional, technical and vocational education and training.

WHO is developing a global competency framework for UHC (31) which will focus on health-care interventions across promotive, preventative, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services, which can be provided by health professionals and community health workers at the primary health care level with a pre-service training pathway of 12–48 months (31). The framework will focus on the competencies (integrated knowledge, skills and behaviours) required to provide interventions and will have relevance to both pre-service and in-service education and training. The term “health workforce” here refers to those front-line health workers providing services targeted to patients and populations such as, but not limited to, physicians, doctors, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, lay health workers, managers and allied health professionals, including community health workers.

Members of the health workforce will need the ability to promote people’s health-related human rights, and to enable individuals to become active participants of their own health care. The WHO European Region proposed the following core competencies for patient advocacy (32).

- Advocate for the role of individuals (and family members if appropriate) in making health-care decisions.

- Familiarize oneself with individual rights and professional obligations to provide safe, high-quality, affordable health and social care, by studying legal instruments: legal rights/civil law; quasi-legal rights, patient charters, patients’ bill of rights and consumer protection policies.

- Educate people on their right to health care.

- Encourage and promote patients’ broad social participation in governance of clinical settings by providing feedback on services received, building partnerships, engaging in political advocacy, promoting community leadership, collecting good data on social conditions and institutional factors, and enhancing communication for health equity.

- Advocate for the incorporation of patient outcomes into organizational strategies, with a special focus on vulnerable populations.

- Understand the effects of disparities in the quality of health care and in people’s access to it.

The reorientation of the health workforce will also require health workers to “approach patients, clients and communities differently, be more open to working in teams (particularly inter-professional teams), use data more effectively in their work and be willing to innovate in their practice” (33).

Furthermore, should the use of a self-care intervention lead to the need for further support or counselling within the health system (e.g. a positive test result), the ability to create conditions for providing coordinated and integrated services – centred on the needs, values and preferences of people – along a continuum of care and over the life course requires the following additional competencies.

- Comprehend that effective care planning requires creating a trusting relationship with the patient, by having several discussions with the patient and other parties, over time.

- Provide patient care that is timely, appropriate and effective for treating health problems and promoting health.

- Screen patients for multi-morbidity and assess cognitive impairment, mental health problems (including risky, harmful or dependent use of substances) and harm to self or others, as well as abuse, neglect and domestic violence.

- Assess the extent of the patient’s personal and community support network and socioeconomic resources, which may impact the patient’s health.

- Match and adjust the type and intensity of services to the needs of the patient over time, ensuring timely and unduplicated provision of care.

- Balance the patient’s care plan with an appropriate combination of medical and psychosocial interventions.

- Incorporate the patient’s wishes, beliefs and life course into their care plan, while minimizing the extent to which provider preconceptions of illness and treatment obscure those expressed needs.

- Manage alternative and conflicting views (if appropriate) from family members, carers, friends and members of the multidisciplinary health-care team, to maintain focus on patient well-being.

- Use focused interventions to engage patients and increase their desire to improve their health and adhere to care plans (e.g. using motivational interviewing or motivational enhancement therapy).

- Assess all health behaviours, including treatment adherence, in a non-judgemental manner.

Health systems, and the training needs of health-care providers, have to be understood not only in relation to the communities and populations they are trying to serve but also in the wider sociocultural, economic, political and historical context in which they are situated and shaped. In order for self-care interventions to be successfully accessed and used, learning, communication and intersectoral collaboration are needed, to facilitate respectful engagement between community members, patients, health professionals and policy-makers. Respectful, non-judgemental, non-discriminatory attitudes of the health workforce will be essential for the effective introduction of self-care interventions. This includes, for instance, demonstrating active, empathic listening, and conveying information in a jargon-free and non-judgemental manner.

Adequate training and sensitization around a mode of service delivery that promotes user-led approaches and autonomy will require pre- and in-service training and on-the-job supervision. Furthermore, interdisciplinary approaches to promote inter-professional teamwork would enable optimization of the skills mix and delegation of roles through task sharing for delivery of services, with users themselves being recognized as “co-producers” of health. Furthermore, pre-service training through high-quality competency-based training curricula is more effective than one-off in-service interventions in terms of bringing about behaviour change for health.

5.5. Implementation Considerations for Vulnerable Populations

5.5.1. New good practice statements on self-care for people of all ages, those in humanitarian settings, and by use of digital health interventions

i. Background

Under a life-course approach, health and the risk of disease are understood as the result of the life experiences, social and physical exposures throughout an individual’s life, from gestation to late adulthood (35). This approach promotes timely interventions to support the health of individuals at key life stages, calling for actions targeting whole societies as well as the causes of disease and ill health, rather than just targeting the consequences in individuals. In sum, a life-course approach to health and well-being means recognizing the critical, interdependent roles of individual, inter-generational, social, environmental and temporal factors in the health and well-being of individuals and communities (36).

The main outcome of the life-course approach is functional ability, which is determined by the individual’s intrinsic capacity in their interactions with their physical and social environments and which is, thus, interdependent with the realization of human rights (37). Functional ability allows people to do what they value doing, which enables well-being at all ages, from gestation and birth, through infancy, early childhood, adolescence and adulthood, to older adulthood (38).

ii. Barriers to SRHR

A lack of systematic knowledge about the way health at different life stages interrelates and accumulates through a lifetime and generations is one of the main barriers to the implementation of the life-course approach to support health and well-being, including SRHR. There are few studies on this issue, most of them focusing on populations in the Global North. An obstacle to improving the understanding of health through time is the current focus on single diseases and specific age groups.

Age-based discrimination is another of the main barriers standing in the way of a better understanding of the SRHR needs of populations in particular age stages; for instance, notions about the sexual lives, needs and health of older populations and adolescents are often clouded by stereotypes. Discrimination against older populations has received increased attention since the 1980s, when the term “ageism” was coined to refer to this particular kind of age-based discrimination (39).

Better understanding of these barriers – and of why people will access self-care rather than facility-based health services – can allow for better use and uptake of self-care interventions. Reducing age-based discrimination and shifting the focus of research and action so that they take into account temporality and interconnectedness is critical to better tailor policy and actions.

iii. Components of an enabling environment that will address the barriers and support SRHR

Age-friendly environments will enable the SRHR needs of populations to be better addressed across the entire age spectrum. Fostering age-friendly environments, which entails reducing ageism, is part of WHO’s Global Strategy on Ageing and Health (40). The United Nations and the Decade of Action on Healthy Ageing, to be launched in 2020 (41) recognize healthy ageing as a contributing factor to the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (42).

Based on case studies carried out by WHO on the implementation of the life-course approach to health in the small European countries of Iceland and Malta, three additional enabling factors were identified. The first entails strengthening collaboration across different government areas, sectors and society, as it was observed that planning and action benefitted from the perspectives and involvement of all actors involved. The second is about making health-care interventions sensitive and responsive to equity and gender, as these two factors are often at the root of disadvantages lasting an individual lifetime and persisting through generations. Finally, the third identified enabling factor was allocating time and resources to monitoring and knowledge exchange; these two activities are key to ensure the adoption and ongoing improvement and durability of the life-course approach and actions (43).

iv. Summary of the evidence and considerations of the GDG

The case of older populations illustrates well the potential benefits of the adoption of a life-course approach to health, particularly SRHR. “Older adults” remains too broad a category, as it is often shorthand for all adults in the second half of life (44). However, older adulthood comprises different stages of life that should be differentiated and better understood in order to meet the SRHR needs of specific stages. WHO currently identifies three age categories in older adulthood: middle adulthood (age 50–64 years) and two age groups in later adulthood (ages 65–79 and 80+) (45). Sexual health remains a key consideration among older adults (46). According to the few systematic reviews on the sexual health of older adults, there is also a lack of diversity in research, as most systematic studies on the matter are based on populations of older adults living in the Global North (47).

A life-course approach that is sensitive, respectful and knowledgeable about the particular challenges and opportunities at all ages would also help reduce age-based discrimination. Stereotypes regarding the sexualities and sexual lives of older adults persist despite various studies that have shown that sex and pleasure are integral to the lives and well-being of older adults. Although this issue remains understudied, the available evidence suggests that supporting older adults’ intrinsic capacities for healthy living includes supporting them in their choice to enjoy safe and fulfilling sexual relationships and sexual pleasure as they age. In order to support informed choices, improving health literacy of older adults regarding accurate information, services and self-care for SRHR remains of the utmost importance.

i. Background

The provision of accurate and tailored information about specific health-care interventions and technologies, including through mobile devices, is important to promote safe and effective SRHR-related self-care. To this end information is needed to:

- facilitate access (e.g. with details of potential sources/access points);

- promote appropriate use of an intervention/technology, through comprehensible (step-by-step) instructions;

- inform potential users about likely physical and emotional ramifications, plus potential side-effects and contraindications; and

- advise potential users about the circumstances under which they should seek care and how to do so.

ii. Barriers to SRHR

Self-care for SRHR has perhaps the greatest potential to address unmet needs or demands in marginalized populations or in contexts of limited access to health care, including, for instance, self-managed medical abortion in countries where abortion is illegal or restricted. In such contexts, a lack of access to specific interventions is often accompanied by a lack of appropriate information regarding the intervention (48) (e.g. when young people obtain emergency contraception from pharmacists but immediately discard the packaging and information sheet because of its potential to incriminate them) and reticence to discuss the intervention because of the associated stigma (49).

Many of the studies of digital health interventions, including use of eHealth and “mobile health” (mHealth, a component of eHealth), which often facilitate targeted client communication or provider-client telemedicine, recognize issues around access (particularly in relation to the availability of mobile phones and connectivity) as well as potential issues of confidentiality. There are also limitations in terms of the research conducted on these interventions; data on health outcomes are limited and the studies rarely use a rigorous research design (50).

iii. Components of an enabling environment that will address the barriers and support SRHR

Digital health technologies offer potential conduits for information beyond more traditional information sources in the formal health system. Digital health technologies encompass a variety of approaches to information provision, including targeted provider-to-client communications; client-to-client communications; and on-demand information services for clients (51). In terms of on-demand SRHR information, the Internet is popular, particularly because the information online is available, affordable, anonymous and accessed in private (52, 53). Online discussion forums – using social media or a range of applications (apps) – can be sources of peer-to-peer information around SRHR self-care technologies. With regard to information provision via mobile phones (text message/SMS or apps on smart phones), recent reviews have demonstrated high feasibility and acceptability of the provision of SRHR-related information, with studies also demonstrating knowledge and behaviour change (54).

iv. Summary of the evidence and considerations of the GDG

A recent systematic review of studies of adolescents accessing SRHR information online highlighted a demand for information and education about sexual experiences (not just technical information) and reviewed the impact of accessing information in this way in terms of behaviour change. The review also highlighted how demand for information varied across the adolescent age groups and showed that adolescents were generally good at evaluating information. However, there is a lack of research on the role of social media in providing SRHR-related information. The relatively few studies undertaken highlight issues with measuring impact, limitations of study designs and a lack of standard reporting (55).

Recent reviews highlight how the effectiveness of digital health interventions to provide appropriate information for safe and effective self-care for SRHR is predicated on consideration for: (i) potential users’ access to technology/digital devices, including limited connectivity; (ii) diversity and changes in the types of delivery channels (e.g. text, voice, apps, etc); (iii) age- and population-specific (e.g. gender, sexuality, disability) information priorities and needs; (iv) the need to tailor content and maintain fidelity of messages; (v) concerns about confidentiality; and (vi) current levels of literacy, as well as digital and health literacy.

Additionally, the WHO guideline: recommendations on digital health interventions for health system strengthening presents 10 recommendations on digital health interventions, based on an assessment of their effectiveness (benefits and harms), as well as considerations of resource use, feasibility, equity and acceptability (values and preference) (56).

i. Background

In 2015, UNHCR – the United Nations Refugee Agency – estimated that the global population of forcibly displaced people exceeded 65 million for the first time in history. Of those needing humanitarian assistance, it is estimated that approximately 1 in 4 are women and girls of reproductive age. The diversity in populations (refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons), settings (from refugee camps to urban areas), circumstances (conflict, post-conflict, natural disasters) and their varying access to rights (e.g. citizens versus non-citizens) all add to the complexity of providing quality care in challenging circumstances (57). With approximately 40% of refugees experiencing displacement for over five years, and many for over 20 years, this underscores the need for a life-course approach to health care for refugees (58).

ii. Barriers to SRHR

The ability to realize SRHR in the context of humanitarian crises is constrained by a complex interplay of factors, including increased poverty; gender-based violence; trauma and mental health challenges; limited access to and quality of health care; breakdown of familial, social and community networks; and problematic living conditions (59). Language also often presents a barrier to health-care access and may result in avoidance of care, misdiagnosis and decreased medical compliance. Thus, there is a need to adapt innovative SRHR service-delivery models for humanitarian contexts (60).

iii. Components of an enabling environment that will address the barriers and support SRHR

Health system strengthening during emergencies remains essential to support and facilitate access to self-care interventions for SRHR. Communities also respond on their own to crises, developing informal yet strong social support systems and an enabling environment. All these are entry points to supporting individuals to improve health outcomes (57). The growing evidence base on implementing comprehensive approaches to delivery of the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) will support improved health outcomes, but there is still much work to be done in this field (61).

iv. Summary of the evidence and considerations of the GDG

Given the lack of longitudinal data or studies with an adequate control comparison group, innovative ways of collecting data should be tested, such as using information and communications technologies (ICTs) that are widely used by many conflict-affected populations (e.g. WhatsApp). These data-collection methods may prove beneficial for researchers, health-care providers and organizations seeking to collect health outcome data at the individual-level, including from populations on the move who have traditionally been challenging to follow up (60). There is also a need for innovation in establishing stronger referral and follow-up systems in humanitarian settings to ensure that health outcome indicators used to assess effectiveness are truly the most appropriate for this purpose. Researchers should also consider use of alternative study designs where standard randomized controlled trials are not operationally or ethically possible (60).

5.5.2. Adapted and existing good practice statements on self-care for vulnerable populations

i. Background

People from vulnerable populations1 should enjoy the same reproductive health and rights as all other individuals; it is important that they have access to family planning and other reproductive health services, including reproductive tract cancer prevention, screening and treatment.

As described in WHO’s Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, efforts to reduce stigma and discrimination at the national level, such as promoting antidiscrimination and protective policies for all key populations, can foster a supportive environment, particularly within the health-care and justice systems – and the same applies to other vulnerable populations. Policies are most effective when they simultaneously address individual, organizational and public policy factors that enable or drive stigma and discrimination. Programmes, both within and outside the health sector, need to institute anti-stigma and antidiscrimination policies and codes of conduct. Monitoring and oversight are important to ensure that standards are implemented and maintained. Additionally, mechanisms for anonymous reporting should be made available to anyone who may experience stigma and/or discrimination when they try to obtain health services (17).

Laws and policies can help to protect the human rights of vulnerable populations. Legal reforms, such as decriminalizing sexual behaviours and legal recognition of transgender status are critical enablers that can change a hostile environment to a safe and supportive, enabling environment. Specific consideration should be given to such legal reforms as part of any revision of policies and programmes for vulnerable populations. Supporting the health and well-being of vulnerable populations may require changing legislation and adopting new policies and protective laws in accordance with international human rights standards. Without protective policies, barriers to access, uptake and use of essential health services – including self-care interventions – will remain (17).

References for Chapter 5

- 1.

- Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture: an exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 1980.

- 2.

- Whyte SR, van der Geest S, Hardon A. Social lives of medicines. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

- 3.

- Hardon A, Sanabria E. Fluid drugs: revisiting the anthropology of pharmaceuticals. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2017;46:117–32.

- 4.

- Kleinman A. Concepts and a model for the comparison of medical systems as cultural systems. Soc Sci Med. 1978;12(2B):85–95. doi:10.1016/0160-7987(78)90014-5. [PubMed: 358402] [CrossRef]

- 5.

- Hardon A, Pell C, Taqueban E, Narasimhan M. Sexual and reproductive self care among women and girls: insights from ethnographic studies. BMJ. 2019;365:l1333. doi:10.1136/bmj.l1333. [PMC free article: PMC6441865] [PubMed: 30936060] [CrossRef]

- 6.

- Safe management of wastes from health-care activities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 (https://www

.who.int/water _sanitation_health /publications/wastemanag/en/, accessed 7 May 2019). - 7.

- Almost a quarter of all disease caused by environmental exposure. In: Media Centre, World Health Organization [website]. 2006 (https://www

.who.int/mediacentre /news/releases/2006/pr32/en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 8.

- Prüss-Üstün A, Wolf J, Corvalán C, Bos R, Neira M. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 (https://www

.who.int/quantifying _ehimpacts /publications/preventing-disease/en/, accessed 22 February 2019). - 9.

- Health-care waste: key facts. In: World Health Organization [website]. 2018 (http://www

.who.int/news-room /fact-sheets /detail/health-care-waste, accessed 18 February 2019). - 10.

- World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund. Water, sanitation and hygiene in health care facilities: status in low- and middle-income countries and way forward. Geneva: WHO; 2015 (https://www

.who.int/water _sanitation_health /publications/wash-health-care-facilities/en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 11.

- About WHO: procurement at WHO. In: World Health Organization [website]. 2019 (https://www

.who.int/about /finances-accountability /procurement/en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 12.

- Chartier Y, Emmanuel J, Pieper U, Prüss A, Rushbrook P, Stringer R, et al. Safe management of wastes from health-care activities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 (https://www

.who.int/water _sanitation_health /publications/wastemanag/en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 13.

- Safe health-care waste management: policy paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004 (https://www

.who.int/water _sanitation_health /medicalwaste/en/hcwmpolicye.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 14.

- Safe health-care waste management: WHO core principles for achieving safe and sustainable management of health-care waste: policy paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007 (https://www

.who.int/water _sanitation_health /facilities/waste/hcwprinciples.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 15.

- Narang A. Sustainable Health in Procurement Project: orientation, planning and inception workshop. Workshop report. 17–19 April 2018, Istanbul, Turkey. Istanbul: United Nations Development Programme Istanbul Regional Hub; 2018 (https://issuu

.com/informal _int_task_team_sphs /docs/shipp_inception _workshop_report, accessed 17 May 2019). - 16.

- 2015 Annual Report of the informal Interagency Task Team on Sustainable Procurement in the Health Sector (SPHS). Istanbul: United Nations Development Programme Istanbul Regional Hub; 2016 (https://www

.undp.org /content/dam/rbec/docs /SPHS_Annual_Report_2015.pdf, accessed 7 May 2019). - 17.

- Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 (https://www

.who.int/hiv /pub/guidelines/keypopulations/en/, accessed 3 May 2019). [PubMed: 25996019] - 18.

- The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 (https://www

.who.int/whr/2010/en/, accessed 19 February 2019). - 19.

- Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. Washington (DC): World Bank: 2017 (http://documents

.worldbank .org/curated/en /640121513095868125 /Tracking-universal-health-coverage-2017-global-monitoring-report, accessed 18 February 2019). - 20.

- Panagioti M, Richardson G, Small N, Murray E, Rogers A, Kennedy A, et al. Self-management support interventions to reduce health care utilisation without compromising outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:356. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-356. [PMC free article: PMC4177163] [PubMed: 25164529] [CrossRef]

- 21.

- Organization of services for mental health. Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003:34 (https://www

.who.int/mental_health /policy /services/essentialpackage1v2/en/, accessed 1 May 2019). - 22.

- Global health and foreign policy. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 12 December 2012. New York (NY): United Nations; 2013 (A/RES/67/81; https://www

.un.org/en /ga/search/view_doc .asp?symbol=A/RES/67/81, accessed 15 May 2019). - 23.

- Universal health coverage: lessons to guide country actions on health financing. World Health Organization, The Rockerfeller Foundation, Health For All, Save the Children, One Million Community Health Workers Campaign; undated (https://www

.who.int/health_financing /UHCandHealthFinancing-final.pdf, accessed 15 May 2019). - 24.

- World Health Organization (WHO), World Bank Group. Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report. Geneva: WHO; 2015 (https://www

.who.int/healthinfo /universal_health_coverage /report/2015/en/, accessed 16 May 2019). - 25.

- Remme M, Narasimhan M, Wilson D, Ali M, Vijayasingham L, Ghani F, Allotey P. Self care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights: costs, benefits, and financing. BMJ. 2019;365:l1228. doi:10.1136/bmj.l1228. [PMC free article: PMC6441864] [PubMed: 30936210] [CrossRef]

- 26.

- Di Giorgio L, Mvundura M, Tumusiime J, Namagembe A, Ba A, Belemsaga-Yugbare D, et al. Costs of administering injectable contraceptives through health workers and self-injection: evidence from Burkina Faso, Uganda, and Senegal. Contraception. 2018;98(5):389–95. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.05.018. [PMC free article: PMC6197836] [PubMed: 29859148] [CrossRef]

- 27.

- Di Giorgio L, Mvundura M, Tumusiime J, Morozoff C, Cover J, Drake JK. Is contraceptive self-injection cost-effective compared to contraceptive injections from facility-based health workers? Evidence from Uganda. Contraception. 2018;98(5):396–404. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.07.137. [PMC free article: PMC6197841] [PubMed: 30098940] [CrossRef]

- 28.

- Consolidated guideline on sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://www

.who.int/reproductivehealth /publications /gender_rights /srhr-women-hiv/en/, accessed 3 May 2019). [PubMed: 28737847] - 29.

- Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 (https://www

.who.int/hrh /resources/globstrathrh-2030/en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 30.

- Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce. Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 (https://apps

.who.int /iris/bitstream/handle /10665/250047/9789241511308-eng.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 31.

- Fitzpatrick S. Developing a global competency framework for universal health coverage. Blog post. In: World Health Organization, Health workforce [website]. 2019 (https://www

.who.int/hrh /news/2018/developing-global-competency-framework-universal-health-coverage /en/, accessed 12 February 2019). - 32.

- Langins M, Borgermans L. Strengthening a competent health workforce for the provision of coordinated/integrated health services: working document. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 2015 (http://www

.euro.who.int /__data/assets/pdf_file /0010/288253/HWF-Competencies-Paper-160915-final.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 33.

- People-centred and integrated health services: an overview of the evidence: interim report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015: 32 (https://apps

.who.int /iris/bitstream/handle /10665/155004/WHO_HIS_SDS_2015 .7_eng.pdf, accessed 7 March 2019). - 34.

- Community engagement for quality, integrated, people-centred and resilient health services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (WHO/HIS/SDS/2017.15; https://apps

.who.int /iris/bitstream/handle /10665/259280/WHO-HIS-SDS-2017 .15-eng.pdf, accessed 19 February 2019). - 35.

- Jacob CM, Baird J, Barker M, Cooper C, Hanson M. The importance of a life course approach to health: chronic disease risk from preconception through adolescence and adulthood. White Paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://www

.who.int/life-course /publications /life-course-approach-to-health.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 36.

- Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century. The Fourth International Conference on Health Promotion: New Players for a New Era, Jakarta, 21–25 July 1997. In: World Health Organization [website]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 (https://www

.who.int/healthpromotion /conferences /previous/jakarta/declaration/en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 37.

- World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 (https://www

.who.int/ageing /publications/world-report-2015 /en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 38.

- Kuruvilla S, Sadana R, Villar Montesinos E, Beard J, Franz Vasdeki J, Araujo de Carvalho I, et al. A life-course approach to health: synergy with sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:42–50. doi:10.2471/BLT.17.198358. [PMC free article: PMC5791871] [PubMed: 29403099] [CrossRef]

- 39.

- Butler RN. Ageism: a foreword. J Soc Issues. 1980:36(2):8–11. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1980.tb02018.x. [CrossRef]

- 40.

- Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://www

.who.int/ageing /WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 41.

- 10 priorities towards a decade of healthy ageing. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (WHO/FWC/ALC/17.1; https://www

.who.int/ageing /WHO-ALC-10-priorities.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 42.

- Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In: Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform [website]. New York (NY): United Nations; 2015 (https:

//sustainabledevelopment .un.org/post2015 /transformingourworld, accessed 18 February 2019). - 43.

- The life-course approach: from theory to practice: case stories from two small countries in Europe. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 2018 (https://issuu

.com/whoeurope /docs/the_life-course_approach, accessed 18 February 2019). - 44.

- Hinchliff S. Sexual health and older adults: suggestions for social science research. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24(48):52–4. [PubMed: 28024677]

- 45.

- Women’s and girls’ health across the life course: top facts: pregnancy, childbirth and newborn. In: World Health Organization [website]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (http://www

.who.int/life-course /news/women-and-girls-health-across-life-course-top-facts/en/, accessed 18 February 2019). - 46.

- Narasimhan M, Beard JR. Sexual health in older women. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(9):707–9. doi:10.2471/BLT.13.119230. [PMC free article: PMC3790224] [PubMed: 24101788] [CrossRef]

- 47.

- Sinkovic M, Towler L. Sexual aging: a systematic review of qualitative research on the sexuality and sexual health of older adults. Qual Health Res. 2018:1–16. doi:10.1177/1049732318819834. [PubMed: 30584788] [CrossRef]

- 48.

- Wainwright M, Colvin CJ, Swartz A, Leon N. Self-management of medical abortion: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24(47):155–67. [PubMed: 27578349]

- 49.

- Both R, Samuel F. Keeping silent about emergency contraceptives in Addis Ababa: a qualitative study among young people, service providers, and key stakeholders. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):1–11. [PMC free article: PMC4228100] [PubMed: 25370200]

- 50.

- Ippoliti NB, L’Engle K. Meet us on the phone: mobile phone programs for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-to-middle income countries. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):11. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0276-z. [PMC free article: PMC5240300] [PubMed: 28095855] [CrossRef]

- 51.

- Classification of digital health interventions v1.0: a shared language to describe the uses of digital technology for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (https://apps

.who.int /iris/handle/10665/260480, accessed 16 May 2019). - 52.

- Simon L, Daneback K. Adolescents’ use of the internet for sex education: a thematic and critical review of the literature. Int J Sex Health. 2013;25(4):305–19. doi:10.1080/19317611.2013.823899. [CrossRef]

- 53.

- Fahy E, Hardikar R, Fox A, Mackay S. Quality of patient health information on the Internet: reviewing a complex and evolving landscape. Australas Med J. 2014;7(1):24–8. doi:10.4066/AMJ.2014.1900. [PMC free article: PMC3920473] [PubMed: 24567763] [CrossRef]

- 54.

- L’Engle KL, Mangone ER, Parcesepe AM, Agarwal S, Ippoliti NB. Mobile phone interventions for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160884. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0884. [PubMed: 27553221] [CrossRef]

- 55.

- Gabarron E, Wynn R. Use of social media for sexual health promotion: a scoping review. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1):32193. doi:10.3402/gha.v9.32193. [PMC free article: PMC5030258] [PubMed: 27649758] [CrossRef]

- 56.

- WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organizaiton; 2019 (https://www

.who.int/reproductivehealth /publications /digital-interventions-health-system-strengthening/en/, accessed 23 May 2019). [PubMed: 31162915] - 57.

- WHO meeting on ethical, legal, human rights and social accountability implications of self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health: 2–14 March 2018, Brocher Foundation, Hermance, Switzerland: summary report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (https://www

.who.int/reproductivehealth /publications /self-care-interventions-for-SRHR/en/, accessed 17 May 2019). - 58.

- Global trends: forced displacement in 2017. Geneva; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); 2017 (http://www

.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf, accessed 18 February 2019). - 59.

- Blanchet K, Ramesh A, Frison S, Warren E, Hossain M, Smith J, et al. Evidence on public health interventions in humanitarian crises. Lancet. 2017;390(10109):2287–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30768-1. [PubMed: 28602563] [CrossRef]

- 60.

- Singh NS, Smith J, Aryasinghe S, Khosla R, Say L, Blanchet K. Evaluating the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0199300. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0199300. [PMC free article: PMC6035047] [PubMed: 29980147] [CrossRef]

- 61.

- Singh NS, Aryasinghe S, Smith J, Khosla R, Say L, Blanchet K. A long way to go: a systematic review to assess the utilization of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(2):e000682. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000682. [PMC free article: PMC5935157] [PubMed: 29736272] [CrossRef]

Footnotes

- 1

See definition in Annex 4: Glossary.

Publication Details

Copyright

Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. To submit requests for commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing.

Third-party materials. If you wish to reuse material from this work that is attributed to a third party, such as tables, figures or images, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuse and to obtain permission from the copyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of any third-party-owned component in the work rests solely with the user.

Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”.

Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Publisher

World Health Organization, Geneva

NLM Citation

WHO Consolidated Guideline on Self-Care Interventions for Health: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. 5, Implementation Considerations and Good Practice Statements on Self-Care.