5.1. Patient flow overview

Burn-injured patients require timely and appropriate care from the scene of the incident onwards.

Phase 1. On-scene: The scene of the incident and the site where first responders are most likely to attend to patients. First responders may include passers-by, local community members, emergency service personnel and health-care workers. Patients should be moved from the scene to the first receiving hospital/s by any form of transport available. Neither BAT nor BST should assist at the scene of the incident unless specifically requested. The roles of BATs and BSTs are deemed most suitable from the first receiving hospital onwards in the patient journey.

Where applicable, a health post should be considered an extension of the scene.

Phase 2. First receiving hospital: This facility is ideally a district-level hospital although it may be a tertiary hospital depending on the site of the incident and self-presentation of patients. Existing burn care capability, such as the presence of experienced health-care workers, burn care beds and appropriate operating facilities, is likely to be highly varied; however, all are likely to have the capability to deliver basic burns care of pain relief, wound cleaning and dressing. Some district hospitals may have the capability of delivering an intermediate level of burns care without additional support from BATs and/or BSTs.

To ensure early, appropriate and optimal patient care and support for local health-care teams, it is recommended that all first receiving hospitals attain intermediate burn-care capability, as needed, with support from deployed BATs and/or BSTs.

Phase 3. Transfer and referral: To target and utilize resources efficiency, referral and transfer of burn-injured patients should be viewed as multi-directional rather than a unidirectional “step-up” transfer from a district hospital to a tertiary hospital. Burn-injured patients requiring higher acuity and more specialist care should be transferred from the first receiving health facility to a tertiary hospital capable of delivering a higher level of burn care. Generally, these are patients with > 20 % TBSA burns and/or deep dermal or “special area” burns (see section on special area burns).

Consideration should also be given to decompress tertiary hospitals by transferring less severely injured burn patients (and non-burn-injured patients) to a district hospital to maximize specialist bed availability and preserve specialist resources. Decisions regarding patient referral and transfer are recommended to occur only after definitive triage has been undertaken by the first receiving hospital (with support from BATs and/or BSTs, as required). The burn care provision of a receiving health facility can be strengthened by incoming BATs and/or BSTs who can support the scale up of resources required to manage a large influx of patients while maintaining adequate level of burn care capability (Table 7).

Any transfer of a patient between hospitals should only occur once the patient is clinically stable and there has been appropriate communication between the referring and receiving hospital. Support from a central coordination hub may also be required.

Suggested provision of burn care during a mass burn incident by level of health facility.

5.2. Triage

Triage is a dynamic process and will likely occur multiple times for the same patient, especially in an MCI. In MCIs, both trauma and/or burns may result and thus a rapid assessment and triage of injuries is required.

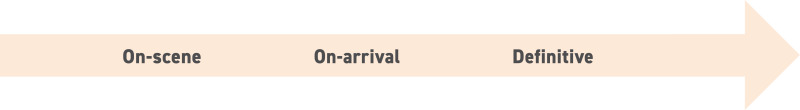

In general, three phases of triage are suggested to occur:

A three-phased triage approach is important, in part to ensure accurate patient assessment following an evolving injury, but also to ensure patients are provided the most suitable interventions for their burn injury in a timely manner. The three-phase triage approach also helps target limited national and international resources to needs, such as specialist beds and intensive care.

5.2.1. On-scene at site of incident

The first phase of triage occurs at the site of the incident. The first responder pool will vary in their experience of assessing injured patients and thus guidance should be familiar, simple and practical in its approach. BATs may support this as requested by local authorities.

General triage

Existing and conventional triage systems such as the WHO/ICRC/MSF/IFRC Integrated Interagency Triage Tool (20) or other standardized tools such as the Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment (START) (21) system should be applied to identify life-threatening injuries such as those compromising the airway (including inhalational burns, head and neck injuries), breathing (such as circumferential full thickness chest burns) or circulation (such as those causing massive haemorrhage). Patients are assigned an appropriate triage category according to the tool used.

The decision to assign a patient to the “expectant” or “non-survivable” or similar triage category is often difficult and sensitive within cultures and communities. Due to the dynamic nature of burn size estimation and potential on-scene estimation error, decision-making regarding survivability of a burn injury is recommended to occur at the first receiving health facility, ideally under expert guidance rather than on-scene.

General triage

Existing and conventional triage systems such as the WHO/ICRC/MSF/IFRC Integrated Interagency Triage Tool (20) or other standardized tools such as the Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment (START) (21) system should be applied to identify life-threatening injuries such as those compromising the airway (including inhalational burns, head and neck injuries), breathing (such as circumferential full thickness chest burns) or circulation (such as those causing massive haemorrhage). Patients are assigned an appropriate triage category according to the tool used.

The decision to assign a patient to the “expectant” or “non-survivable” or similar triage category is often difficult and sensitive within cultures and communities. Due to the dynamic nature of burn size estimation and potential on-scene estimation error, decision-making regarding survivability of a burn injury is recommended to occur at the first receiving health facility, ideally under expert guidance rather than on-scene.

Burn specific triage: %TBSA burn estimation

Following conventional triage, assessment of burn severity can occur. On-scene assessment of burn severity should be determined mainly from %TBSA burn size estimation rather than depth assessment.

Estimation of %TBSA burn at scene supports a simple but early effective approach to initial burn triage. Mortality from burns is multifactorial although the relationship between %TBSA burn and survival is well known (22). Depth should not be used as a severity assessment factor as scene responders may not be experienced nor trained in burn injury depth assessment. Additionally, the depth of a burn changes over time and can be difficult to assess even by burns specialists in the first 24 hours (23). Over and underestimation of %TBSA burn is likely to occur on-scene, and environmental and cultural constraints may impact on how easily burn size estimation can occur (24). A 2019 systematic literature review identified %TBSA burn miscalculations from 5 % to 339 % regardless of provider level with < 20 % TBSA burns being disproportionately overestimated (25). Thus, reassessment and re-triage on arrival at the first receiving hospital, and subsequently by burn-experienced staff, is essential.

The %TBSA burn size estimation tool utilized on scene should reflect the tool most familiar to the first responder. This is likely to reduce error and support an easy-to-use assessment for first responders to determine %TBSA burn. However, should guidance be required, the Wallace Rule of Nines %TBSA burn estimation tool should be used for adults (with the accompanying modified version for children) (26). This method is simple, applicable across a variety of contexts, and is a commonly used burn size estimation tool used in pre-hospital environments (27). On arrival at the first receiving health facility, additional tools and burn-experienced health-care workers may be available to re-estimate %TBSA burn as part of the overall reassessment and triage of the patient.

For an approach to further simplify %TBSA-based burn specific triage (which occurs only after general triage as appropriate), the guide below in Table 8 may be considered, taking into account additional special considerations such as age of the patient.

Guide to %TBSA-based burn specific triage.

5.2.2. On-arrival at first receiving health facility

The second phase of triage is recommended to occur at the first receiving facility immediately on patient arrival. BATs and/or BSTs are well placed to support both arrival and definitive triage.

On-arrival triage supports a re-evaluation of each patient with consideration given to survivability factors such as %TBSA burn, age, depth and site of burn, and patient comorbidities (Table 9). Burn size %TBSA recalculation at this stage may be completed using additional tools.

It should be noted that across all contexts paediatric burns are routinely difficult to assess and may result in over-estimation of burn size by the first receiving hospital compared to a specialist burns unit thus impacting transfer decisions (28). Regular reassessment and re-triage supported by burns expertise is critical.

Factors to consider during on-arrival and definitive triage.

On arrival at the first receiving health facility the decision to assign a patient to the “Expectant” or “Non-survivable” or similar triage category remains difficult and sensitive. Support for such decision-making is recommended and can be offered by the BAT and/or BST. Once a decision has been made by the treating health-care team, implementation of palliative care interventions (see Table 10) is essential to ensure the patient’s dignity and comfort. Consideration should also be given to the needs of the patient’s family.

Patients with non-survivable injuries should be nursed at the health facility where they have been initially received. However, this decision should be at the discretion of the treating clinicians and may be influenced by availability of nursing care and locality of patient family.

Palliative care recommendations.

5.2.3. Definitive (after surgical scrub/wound cleaning)

The third phase of triage should also be undertaken at the first receiving health facility. Definitive triage should occur after extensive wound cleaning and/or surgical scrub, meaning when the extent, site and severity of burn injuries can be more accurately determined. BATs and/or BSTs are well placed to support both arrival and definitive triage.

A three-phased triage approach is important in part to ensure accurate patient assessment following an evolving injury, but also to ensure patients are provided with the most suitable interventions for their burn injury in a timely manner. The three-phase triage approach also helps in timely recruitment of national and international resources to appropriately deal with higher-care resource needs such as specialist beds and intensive care.

On-arrival and definitive triage should include an assessment of burn depth. Other survivability factors including patient age and comorbidities should also be considered during these phases of triage (Table 9). Decisions regarding onward clinical care and redistribution of patients can then be considered once a more accurate patient assessment has been completed. Paediatric burns > 10 % TBSA (determined after definitive triage), inhalational burns, special area burns and specific chemical burns should be triaged and managed in a tertiary hospital when possible.

5.3. Special area burns

Burns affecting the face, neck, perineum, genitalia, joints, hands and feet are designated special area burns. Burn expertise with BAT and/or BST support may be required to manage patients sustaining these kinds of burn injuries, regardless of %TBSA affected. Access of such patients to specialist care (such as rehabilitation specialists) is recommended to expedite and optimize recovery.

5.4. Inhalation injury

Inhalational injuries can cause significant morbidity and mortality (29). Early recognition and intervention of likely airway compromise or respiratory failure is an important step towards improving patient outcome. First responders and those at the initial receiving health facility are advised to be observant for early signs and symptoms of a thermal inhalational injury. The type of incident and mechanism of a burn injury will also provide additional indications of the risk of inhalational injury. Signs of inhalational injury include soot in the mouth, facial burns, stridor, hoarseness and confusion (29). Evaluation of inhalational injury is a critical step in the triage process.

Consideration should also be given to the possibility of chemical inhalational injuries, such as those resulting from mustard gas, phosphorus and chlorine following MCIs. Appropriate personal protective equipment is advised when managing patients suspected of being victims of a chemical incident. Additionally, awareness of the often delayed effects of the agent is important (for example, mustard agents) (30). Industrial accidents can also give rise to inhalational injuries such as cyanide poisoning from acrylics (31).

Early and appropriate interventions and referral of patients with suspected inhalational injuries to specialized burn centres can help support improved outcome. Early interventions include airway protection, oxygenation, cautious fluid management and respiratory rehabilitation.

Respiratory complications from inhalation injuries affect each patient differently. These may include: pain, anxiety, increased work of breathing and secretion retention. Early respiratory rehabilitation and optimal early patient positioning can help alleviate symptoms and prevent future complications in addition to ensuring the patient is equipped to manage their symptoms on discharge. Where possible, early mobilization should be encouraged to enable the patient to clear secretions and maintain cardiorespiratory system function. For children, this may take the form of play. A programme of breathing exercises and manual techniques should be used to support the patient to maximize lung function and chest expansion.

Advanced airway management (intubation and ventilation) is resource intense and thus this intervention should be considered at the earliest possible phase of care.

5.5. First aid and dressings

First aid for burn injury influences the clinical course and severity of the burn (32–34). Basic first aid can be continued from on-scene into the first receiving hospital and includes the following.

5.5.1. Cooling

Cooling of the burn wound can occur from 10 minutes to three hours after the injury was sustained using potable/drinking water of room or cool temperature. Cooling is associated with improvement in re-epithelialization over the first two weeks post-burn and decreased scar tissue at six weeks (33, 35). Consideration should be given to patients who are at risk of hypothermia, in which cases resuscitation efforts should be prioritized over burn cooling.

5.5.2. Analgesia

Provision of pain relief is critical for patients with burn injuries and should be offered in conjunction with cooling and/or just before cleaning if possible.

5.5.3. Cleaning

Basic cleaning involves removing debris and irritants from the wound using potable/drinking water of room or cool temperature. Rings, watches or any other jewellery/clothing should be removed from the burned area as swelling will ensue.

Advanced (thorough) cleaning should occur on arrival at the first receiving hospital with appropriate analgesia and/or sedation.

If extensive wound cleaning is required, the surgical scrub of burn wounds can be undertaken in the operating theatre by clinicians while the patient is under anaesthesia. This intervention can be supported by burn experts from the BAT and/or BST.

5.5.4. Dressing

A basic non-circumferential, light, clean dressing or plastic wrap may be applied after basic cleaning. Application of substances such as eggs, butter, toothpaste or similar should be avoided.

More extensive understanding of the pathophysiology of wound healing and developments in dressing technology has resulted in significant advances in burn wound care and dressings (36). There are a number of modernized dressings available that are designed to be left in place for a longer duration than simple daily or alternate day dressings. However, the former may be considerably more expensive.

After wound cleaning, options for dressings should be considered according to:

- (a)

the wound characteristics (for example, infected versus non-infected);

- (b)

point of application (on-scene or health facility);

- (c)

availability of dressings, including routine dressings and/or specialist dressings likely to be externally sourced;

- (d)

cost-benefit implications and resource requirements (such as staffing); and

- (e)

ability of patient to return for follow up.

In a mass burn incident, availability of staff to regularly change dressings and dressing availability (potentially affected by lack of local and international resupply) are likely to be compromised. Consideration also needs to be given to the logistical requirement of transporting dressings if brought to the health facility by a BAT and/or BST, including packaging weight and volume, air transport costs, clinical waste disposal requirements and local transportation.

5.5.5. Tetanus considerations

Confirm if a patient has had their tetanus vaccination and it is up to date as per local guidelines and practices. Give booster and/or immunoglobulin as indicated.

5.6. Out-patient burn management

Effective out-patient care of the burn-injured patient requires patient compliance and adherence to treatment. Clear communication, easily accessible clinics and simple burn care pathways should be made available to patients and their families. Community engagement in burn care and burn prevention is also important and helps provide support for patient recovery.

Patients with < 20 % TBSA superficial/partial thickness burns and no special area burns may be discharged with adequate outpatient support (for example, social and community support and clear care pathway communicated).

Patients with > 20 % TBSA and/or deep dermal or special area burns should be evaluated by an experienced burn care specialist as they may require ongoing in-patient care. Consider transferring these patients to a specialist burn care centre.

5.7. Surgical interventions

Surgical interventions that the local surgical teams are unfamiliar with or inexperienced in should be supported by clinical expertise from BAT and/or BST, supplementing the use of existing procedural guidance and checklists.

Procedures that may be performed by non-burn surgeons include advanced wound cleaning, surgical scrub, escharotomy and fasciotomy. As limb-salvaging and life-saving interventions, escharotomies and/or fasciotomies are deemed to be an important part of the initial management and stabilization approach to burn patients. These may be performed at a first receiving hospital provided infrastructure and local skill sets are available.

Excision, enzymatic debridement, grafting, local tissue rearrangements, flaps and contracture releases are examples of procedures that should be performed by surgeons skilled in burns care and/or by surgeons supported by clinical expertise. Full thickness burns should ideally be managed (excised) within the first week of injury while partial thickness may be managed beyond the first week. Excisions of burns < 20 % TBSA in adults and < 10 % in children may be may be performed at a first receiving hospital, supported by burns expertise, provided infrastructure and local skill sets are available. Only skilled burn surgeons (supporting a district or tertiary hospital) should undertake excision in patients with > 20 % TBSA burn (adult) and > 10 % TBSA burn (children).

5.8. Rehabilitation

Early access to rehabilitation can have a significant impact on patient outcomes and reduce the risk of secondary complications, such as immobility and contractures. The hypermetabolic response from severe burns, coupled with prolonged bed rest make patients vulnerable to secondary complications (37, 38). This is especially critical in the context of limited in-patient bed availability during a mass burn incident.

Active and passive exercises, positioning, splinting and functional retraining should commence at the earliest phase of care, once vital functions are stable and considering precautions such as related trauma, wound breakdown, graft frailty, attached wires, low blood pressure or infection. Adequate analgesia should be administered prior to rehabilitation interventions as pain can reduce participation and performance.

In the context of burn injuries, the focus of rehabilitation is on:

- -

reducing oedema

- -

managing pain

- -

encouraging early mobilization

- -

preventing or reducing disfigurement

- -

supporting functional recovery

- -

minimizing the impact of scarring on range of movement.

Rehabilitation specialists have specific skills to target these objectives. Rehabilitation specialists are potentially also well-suited to take over the care of burns patients once surgical intervention and wound care has been completed. However, improving patient outcomes from burn injury through effective rehabilitation strategies remains the responsibility of the entire treating team in collaboration with the patient (39).

Rehabilitation requirements should be considered for all patients (based on burn severity and location of the burn) on their arrival at the first receiving hospital. Depending on need, rehabilitation interventions may include:

- -

respiratory physiotherapy (see section on inhalation injuries)

- -

stretching and range of movement exercises

- -

strength and coordination exercises

- -

ambulation

- -

activity of daily living/functional retraining

- -

anti-contracture positioning.

Burn contractures can develop within weeks. Splinting and positioning are essential for maintaining tissue length during wound healing and to maximize functioning. Oedema post-burn injury can be aggravated by limb dependency and can restrict wound healing and movement, as well as exacerbate pain (40). Elevated positioning facilitates lymphatic drainage and, along with massage and compression, can be used to effectively manage oedema. When burns are grafted or deep partial or full thickness burns are being managed expectantly, position the burnt/grafted skin to counteract contractile forces, using splints when indicated, to prevent contracture and manage oedema.

- -

Splinting

Splinting can be used post-skin grafting to immobilize the limb. The typical regime post-skin graft is to continually immobilize the affected joint area(s) for five to seven days (depending on the state of the graft take), followed by night-wear of splints. However, this should be decided in consultation with the surgeon. Splints may be applied in theatre while the patient is under anaesthesia or during post-operative recovery to minimize discomfort. The indication for splinting is based on the severity and location of the burn, and the patient’s ability to move actively. Splinting should be particularly considered for young children and sedated patients who may not be able to actively participate in stretching and exercises. Photographs or pictures can be used to illustrate ideal positioning.

Splinting and anti-contracture positioning should be considered for conservatively managed wounds that do not heal within two weeks, as the risk of scarring increases. Thermoplastic is the ideal splinting material as it can be remoulded over time and achieve good conformality, but alternative materials, such as Plaster of Paris and PVC piping may also be considered in more resource-scarce settings. Innovative resources can also be used for mouth (wooden spatula) and neck splint (suction tubes wrapped with cotton and gauze).

- -

Scar management

Compression therapy and massage should be used to minimize scarring and manage oedema. In the context of moderate and severe burns, compression therapy can reduce scar height, and alleviate some of the discomfort of immature scars, such as blood rush and itching. Scar massage similarly works to soften scars and can improve skin movement and reduce hypersensitivity (37).

Compression can be achieved with bandaging, tubular elastic stockings and pressure garments. While customized compression garments may not be available in resource-scarce settings, compression should aim to achieve a pressure of 24 mmHg. Compression bandages or garments should be worn 23 hours a day, with regular monitoring, until scar maturation. Scar maturation can continue for 12–18 months and complications can arise for years following discharge from acute care.

As patients with severe burns will continue to use compression and massage well beyond discharge, education in correct use/technique is critical in addition to education about on-going scar care. Encouraging participation during inpatient stay is important to improving chances of continuity post-discharge. Identification and coordination with local rehabilitation providers and disability organizations is an important aspect of discharge planning, particularly in a mass burn incident. This is especially critical for paediatric patients who will require on-going intervention due to the impact of growth on scar tissue.

5.9. Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) considerations

BATs and BSTs are recommended to have the capability to support the initial care of CBRN patients in the event of a CBRN MCI. They are not expected to deliver care to patients in hot zones, nor involve themselves in scene decontamination but should have provision to provide an early basic package of care to include basic airway management, analgesia, oral rehydration, urinary catheterization, dressings and antibiotics as required (and potentially in the form of patient self-administered kits). Mental health and bereavement support is also suggested. Team members should have good awareness and basic training in CBRN but do not require specialist or higher-level training. Specific knowledge on chemical burns, thermonuclear and radiation burns is recommended when possible.

The general principles of burn care offered by BATs and BSTs can be applied to CBRN incidents. For example, in the event of a thermonuclear mega-event, analgesia, hydration and wound care can be provided by burn teams to support victims.