Abstract

Cdc25 phosphatase primes entry to mitosis by removing the inhibitory phosphate that is transferred to mitosis promoting factor (MPF) by Wee1 related kinases. A positive feedback loop then boosts Cdc25 and represses Wee1 activities to drive full-scale MPF activation and commitment to mitosis. Dominant mutations in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe spindle pole body (SPB) component Cut12 enable cdc25.22 mutants to overcome a G2 arrest at 36° and enter mitosis. The recessive temperature-sensitive cut12.1 mutation results in the formation of monopolar spindles in which the spindle pole marker Sad1 is enriched on the nonfunctional SPB at 36°. We identified mutations at five loci that suppressed the lethality of the recessive cut12.1 mutation at 36° and conferred lethality at 20°. Three of the five mutations led to the formation of monopolar spindles at restrictive temperatures, affected cell size at commitment to mitosis, and generated multiple Sad1 foci at nuclear periphery. The five loci, tfb2.rt1, tfb5.rt5, pla1.rt3, rpl4301.rt4, and rot2.1, and multicopy suppressors, including tfb1+ and dbp10+, are involved in transcription, translation, or RNA processing, prompting us to establish that elevating Cdc25 levels with the dominant cdc25.d1 allele, suppressed cut12.1. Thus, rot mutants provide a further link between protein production and cell-cycle progression.

GENETIC analysis of cell-cycle control in fission yeast and biochemical approaches in Xenopus revealed that commitment to mitosis is controlled by the activity of a conserved protein kinase complex called mitosis promoting factor (MPF) (Nurse 1990). MPF is composed of a catalytic subunit, Cdc2 (known as Cdk1 in several systems), and a regulatory subunit, cyclin B, that is destroyed when cells enter anaphase (Evans et al. 1983). Cdc2 is activated only when the criteria for entrance to mitosis have been fulfilled. In fission yeast these criteria include the attainment of a critical cell volume and the provision of an appropriate nutrient supply to ensure the completion of division (Mitchison 2003). MPF is restrained in an inactive state as a result of inhibitory phosphorylation by Wee1-related kinases until such criteria are fulfilled (Russell and Nurse 1987a; Gould and Nurse 1989; Featherstone and Russell 1991; Parker and Piwnicaworms 1992; McGowan and Russell 1993). This phosphate is then removed at the appropriate time by Cdc25 phosphatase to promote entrance into mitosis (Russell and Nurse 1986). Thus the timing of entrance into mitosis is governed by the balance of Wee1 and Cdc25 activities (Fantes 1983; Nurse 1990).

The activation of a priming level of MPF promotes a positive feedback loop that boosts the activity of Cdc25 and inhibits the activity of Wee1-related kinases (Hoffmann et al. 1993). Studies of MPF activation in Xenopus extracts indicated that, while MPF itself comprised an important part of this positive feedback loop, Cdc25 could still be activated in MPF primed extracts from which all Cdc2 and the related Cdk2 kinase had been depleted and that mutation of MPF consensus phosphorylation sites on Cdc25 did not block activation (Izumi and Maller 1993, 1995). The search for the feedback loop, Cdc25 activating, kinase identified Xenopus polo kinase (Kumagai and Dunphy 1996). Subsequent work consolidated the view that polo kinase constitutes a critical part of the loop in Xenopus extracts (Abrieu et al. 1998; Karaiskou et al. 1999, 2004). Furthermore, phosphorylation of cyclin B by polo kinase is one of the earliest aspects of MPF activation noted in human cells to date (Jackman et al. 2003) and injection of antibodies against polo kinase blocks entrance to mitosis in nontransformed human cell lines (Lane and Nigg 1996). Less is known of Wee1's role in feedback loop activation; however, it is heavily phosphorylated upon mitotic commitment in a range of systems (Tang et al. 1993; Mueller et al. 1995; Watanabe et al. 2004) and budding yeast Wee1, Swe1, has been proposed to interact with and be inhibited by the polo kinase Cdc5 (Bartholomew et al. 2001; Sakchaisri et al. 2004). Recent data suggest that Greatwall kinase works alongside polo as part of the positive feedback loop in Xenopus extracts (Yu et al. 2006).

In S. pombe, the activation of bulk Cdc25 activity requires prior activation of MPF, indicating that it also employs a positive feedback to promote mitosis (Kovelman and Russell 1996). A screen for extragenic suppressors of the conditional cdc25.22 mutation identified three dominant mutations in the stf1+ gene (suppressor of 25) that enabled cells from which cdc25+ had been deleted to proliferate (Hudson et al. 1990, 1991). The same gene was identified in a screen for mutants that increased ploidy after a generation at 36° (Bridge et al. 1998). As the mutant identified in this screen exhibited the “cut” phenotype (Hirano et al. 1986), it was called cut12+. Because the conditional lethal cut12.1 mutation was a recessive mutation and stf1.1 dominant, the gene is referred to as cut12+ and the stf1.1 mutation as cut12.s11.

cut12+ encodes an essential component of the spindle pole body (SPB) (Bridge et al. 1998). In cut12.1 mutants one of the two SPBs fails to nucleate microtubules and the SPB-associated protein Sad1 (Hagan and Yanagida 1995) becomes asymmetric, associating primarily with the inactive SPB. Deletion of the cut12+ gene also blocks spindle formation, but in this case Sad1 shows equal affinity for either SPB (Bridge et al. 1998). In contrast spindle formation and function are unaffected in the cdc25.22-suppressing cut12.s11 allele. Fission yeast polo kinase Plo1 normally associates with the mitotic but not interphase SPBs; however; in cut12.s11 cells Plo1 is prematurely recruited to interphase SPBs (Mulvihill et al. 1999). Furthermore the cut12.s11 mutation boosts Plo1 kinase activity over wild-type levels, whereas cut12.1 blocks the mitotic activation of Plo1 (MacIver et al. 2003). Genetic analyses support a functional link between Cut12 and Plo1 activity because the ability of cut12.s11 to suppress cdc25.22 requires a fully functional Plo1 kinase and activation of Plo1 independently of any change in Cut12 status mimics cut12.s11 in suppressing cdc25.22 (MacIver et al. 2003). Because inactivation of Wee1 overcomes the requirement for Cdc25 (Fantes 1979) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe utilizes a positive feedback loop to promote mitosis (Kovelman and Russell 1996), we proposed that cut12.s11 suppresses defective Cdc25 function by inappropriately promoting Plo1 activity to drive the feedback loop to suppress Wee1 activity. Implicit in this model is a role for Cut12 in the normal controls that regulate mitotic commitment (MacIver et al. 2003).

The ability of the cut12.s11 allele to promote mitosis in cdc25.22 cells and the premature recruitment of Plo1 to the SPB both depend upon the activities of the fission yeast NIMA-related kinase, Fin1, and the p38 equivalent stress response pathway (SRP) kinase Spc1/Sty1 (Grallert and Hagan 2002; Petersen and Hagan 2005). Because the amplitude of SRP signaling is greater in minimal than in rich medium (Shiozaki and Russell 1995), Cut12, Plo1, and the SRP coordinate cell division with the nutrient status of the immediate environment.

A further level of control over the timing of commitment to mitosis in fission yeast is provided by modulation of the level of the mitotic inducers. Both Cdc25 and Cdc13/cyclin B accumulate during interphase to peak in mitosis (Booher and Beach 1988; Creanor and Mitchison 1994). Furthermore, both Cdc25 and the two B-type cyclins, Cdc13 and Cig2, are subject to strict translational control (Daga and Jimenez 1999; Grallert et al. 2000). A sudden reduction in the competence to translate proteins leads to a precipitous drop in cyclin B levels leading to a rapid block of division upon nutrient limitation (Grallert et al. 2000). Similar mechanisms may be employed during checkpoint responses to DNA damage as a DEAD box helicase that has been associated with translational control was identified by a number of groups in a screen of elements that cooperated with Cdc25 to block division when DNA integrity is compromised (Forbes et al. 1998; Grallert et al. 2000) and in a screen for multicopy suppressors of a cold-sensitive, loss-of-function mutant of cdc2 (Liu et al. 2002).

We describe mutations in five loci that both suppress cut12.1 lethality at 36° and confer a cold-sensitive growth defect in their own right. These loci are involved in transcription/translation control. The intimate link between Cdc25 and Cut12 and translational control of Cdc25 (Daga and Jimenez 1999) led us to establish that mutations that elevate Cdc25 levels by removing pseudo-ORFs from the cdc25 5′-UTR (Daga and Jimenez 1999) suppresses cut12.1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, cell culture, and molecular biology:

Strains are listed in Table 1. Standard fission yeast and molecular biology approaches were used throughout (Moreno et al. 1991). For spot tests, cells were grown to midlog phase and serial fivefold dilutions were plated on solid medium. rotx-suppressing plasmids were cloned from a genomic library (Barbet et al. 1992). To generate the cdc25.d1∷leu1 strain, the PstI–SacI fragment from the plasmid pRep3x:cdc25-d1 (Daga and Jimenez 1999) was cloned into pJK148 integrative plasmid (Keeney and Boeke 1994) to generate pJKcdc25-d1. The new plasmid was linearized into the leu1+ marker at the NruI site and transformed into leu1–32, ura4–d18 strain. Leu+ colonies were selected and checked by PCR and crossing to a leu1∷ura4+ strain (0% leu+ ura+) for integration into leu1 locus (strain IH4625).

TABLE 1.

List of strains

| Strain | Genotype | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| IH 163 | 972 h− | Lab stock |

| IH 365 | leu1.32 ura4.d18 h− | Lab stock |

| IH 366 | leu1.32 ura4.d18 his2 h+ | Lab stock |

| IH 3589 | tfb2.rt1 leu1.32 ura4.d18 h− | This study |

| IH 3968 | tfb2.rt1 ura4.d18 leu1.32 ade6-M210 h+ | This study |

| IH 3979 | tfb2.rt1/tfb2+ mei1+/mei1.102 ade6.M210/ade6.M216 | This study |

| IH 693 | tfb2.rt1 cut12.1 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h− | This study |

| IH 4050 | tfb2.rt1 ura4.d18 leu1.32 cdc25+ pRep3Xcdc25.d1 h+ | This study |

| IH 4051 | tfb2.rt1ura4.d18 leu1.32 pREP3Xded1+ h+ | This study |

| IH 3735 | rot2.1 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h+ | This study |

| IH 3969 | rot2.1 leu1.32 ade6-M210 h− | This study |

| IH 3980 | rot2.1/rot2+ mei1+/mei1.102 ade6.M210/ade6.M216 | This study |

| IH 3536 | rot2.1 cut12.1 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h+ | This study |

| IH 2024 | pla1.rt3 cut12.1 his2 leu1.32 ura4.d18 h+ | This study |

| IH 3970 | pla1.rt3 leu1.32 ade6-M210 h− | This study |

| IH 3981 | pla1.rt3/pla1+ mei1+/mei1.102 ade6.M210/ade6.M216 | This study |

| IH 4060 | pla1.rt3 ura4.d18 leu1.32 cdc25+ pRep3Xcdc25.d1 h− | This study |

| IH 4061 | pla1.rt3 ura4.d18 leu1.32 pRep3Xded1+ h− | This study |

| IH 3537 | rpl4301.rt4 cut12.1 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h+ | This study |

| IH 3290 | rpl4301.rt4 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h− | This study |

| IH 3291 | rpl4301.rt4 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h+ | This study |

| IH 3982 | rpl4301.rt4/rpl4301+ mei1+/mei1.102 ade6.M210/ade6.M216 | This study |

| IH 3292 | tfb5.rt5 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h− | This study |

| IH 3293 | tfb5.rt5 ura4.d18 leu1.32 his2 h+ | This study |

| IH 3538 | tfb5.rt5 cut12.1 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h+ | This study |

| IH 4035 | tfb5.rt5/rot5+ mei1+/mei1.102 ade6.M210/ade6.M216 | This study |

| IH 3604 | tfb5.rt5 cdc25.22 ura4.d18 leu1.32 his2 h− | This study |

| IH 4070 | tfb5.rt5 ura4.d18 leu1.32 cdc25+ pRep3Xcdc25.d1 h− | This study |

| IH 4071 | tfb5.rt5 ura4.d18 leu1.32 pRep3Xded1+ h− | This study |

| IH 596 | cut12.1 leu1.32 ura4.d18 h− | Bridge et al. (1998) |

| IH 661 | cut12.1 ade6.704 ura4.d18 leu1.32 his2 h+ | Bridge et al. (1998) |

| IH 3496 | ded1-61 leu1.32 h− | Grallert et al. (2000) |

| IH 3497 | ded1-78 leu1.32 h− | Grallert et al. (2000) |

| IH 3541 | ded1-1D5 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h+ | Grallert et al. (2000) |

| IH 5464 | cut12.1 ded1-1D5 h− | This study |

| IH 5466 | cut12.1 ded1-78 h− | This study |

| IH 4626 | leu1∷cdc25.d1 cdc25+cut12.1 h− | This study |

| IH 4625 | leu1∷cdc25.d1 cdc25+ h+ | This study |

| IH 634 | cdc25.22 ura4.d18 leu1.32 his2 h+ | Lab stock |

| IH 565 | cdc25.22 ura4.d18 leu1.32 h− | Lab stock |

| IH 333 | gtb1+:LEU2+ leu1.32 h− | This study |

| IH3029 | h+ cdc25:12myc:ura4+ ura4.D18 leu1.32 | Lopez-Girona et al. (1999) |

| IH4461 | h− tfb2.rt1 cdc25:12myc:ura4+ ura4.D18 leu1.32 | This study |

| IH4394 | h− rot2.1 cdc25:12myc:ura4+ ura4.D18 leu1.32 | This study |

| IH4395 | h− pla1.rt3 cdc25:12myc:ura4+ ura4.D18 leu1.32 | This study |

| IH4396 | h− rpl4301.rt4 cdc25:12myc:ura4+ ura4.D18 leu1.32 | This study |

| IH3598 | h+ tfb5.rt5 cdc25:12myc:ura4+ ura4.D18 leu1.32 | This study |

Cell biology:

Cells were processed for Western blotting with AP9.2 (anti-Sad1), anti-Cut12, anti-Cdc2 (PN24), or 9E.10 anti-myc epitope monoclonal antibody (Evan et al. 1985; Simanis and Nurse 1986; Hagan and Yanagida 1995; Bridge et al. 1998) according to MacIver et al. (2003). Standard fluorescence procedures that used AP9.2 (anti-Sad1) and TAT1 (anti-α tubulin) antibodies were as described previously (Woods et al. 1989; Hagan and Yanagida 1995). Images were obtained using either a Deltavision Spectris system or an inverted Zeiss axioplan II with a coolsnap camera (Photometrics) driven by the Metamorph (Universal Imaging). Metamorph was used to measure cell lengths. For Figure 4, E and D, and Figure 6C a series of 10–12 × 0.3-μm slices of a single field was captured on the deltavision imaging platform to generate a series of images in the Z axis that was compressed to give the maximal projections shown in Figure 4, E and D, and Figure 6C.

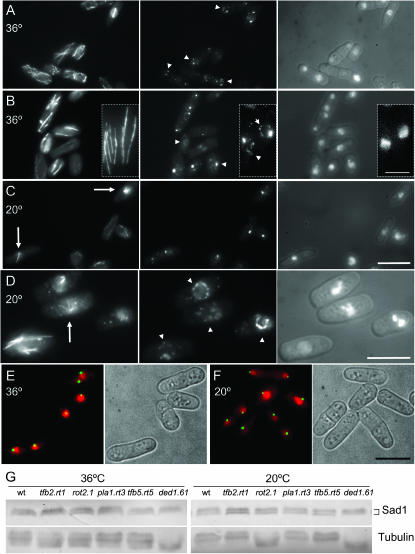

Figure 4.—

rot2.1 mutants form monopolar spindles and multiple Sad1 foci around their nuclear periphery. (A–D) rot2.1 cells were grown to early log phase at 36° before the temperature of the medium was changed to 20°. Immediately before (A and B) and 15 hr after (C and D) the shift cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence to reveal the distribution of microtubules (left), Sad1 protein (middle), and the relative location of the chromatin (right). Arrowheads in A, B, and D indicate the additional spots of Sad1 staining seen on the nuclear periphery while arrows in C and D identify monopolar spindles. Bars, 10 μm; bar in inset, 5 μm. (E and F) Live cell imaging of rot2.1 cut12.NEGFP cells stained with Hoescht 33342 to reveal Cut12 (green) alongside chromatin (red) and brightfield images of cell outlines. While Sad1 forms multiple foci (A–D) the Cut12.GFP signal is still a single discrete dot, indicating that the extra dots of Sad1 seen in rot2.1 cells do not contain Cut12. Imaging cells expressing Sid4.Tdtom also gave single dots at all temperatures (data not shown). (G) Western blots of cell extracts from the indicated strains probed with either AP9.2 anti-Sad1 antibody (top) or TAT1 anti-tubulin (bottom). The altered migration of the tubulin bands was seen in multiple independent experiments. We have not established the nature of the modification that underlies this change in protein migration.

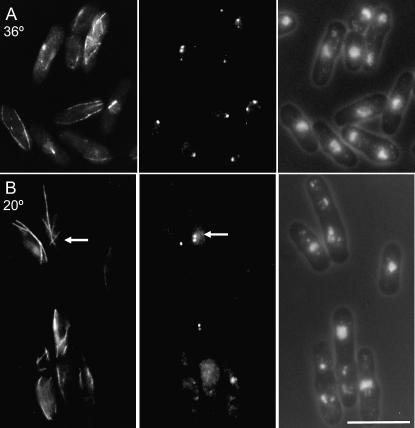

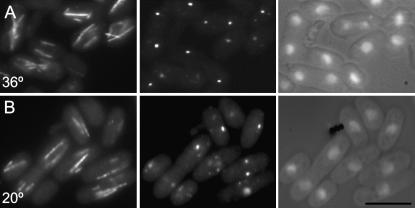

Figure 6.—

ded1.61 cells exhibit a “ban−” phenotype with multiple Sad1 foci around their nuclear periphery at 20°. (A–C) ded1.61 cells were grown to early log phase at 36° before the temperature of the medium was changed to 20°. Fifteen hours after the shift, cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence to reveal the distribution of microtubules (left), Sad1 protein (middle), and the relative location of the chromatin (right). Arrows highlight multiple Sad1 foci. (A and B) Interphase, (C) mitosis. Bars, 10 μm.

RESULTS

Isolation of revertants of cut twelve mutants:

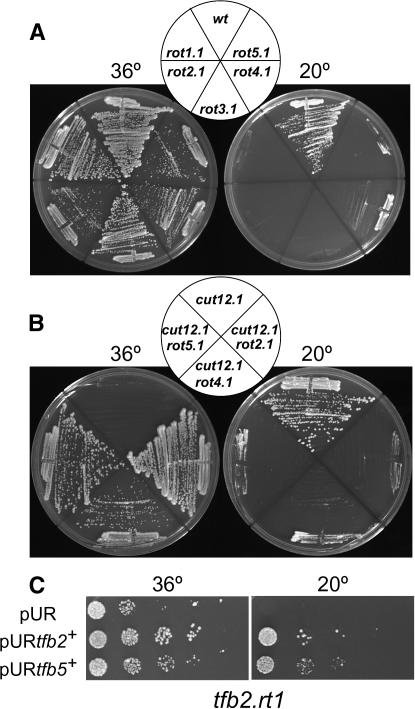

To identify genes that displayed genetic interactions with cut12+, 1000 spontaneous mutants that enabled cut12.1 cells to form colonies at 36° were isolated and streaked at 20° to identify 45 strains that were unable to grow at the lower temperature. Five mutants displayed a strong cold-sensitive phenotype when crossed away from cut12.1 into a cut12+ background (Figure1A). After two further backcrosses, linkage analysis established that the mutants fell into five separate complementation groups, rot1–5 (revertant of twelve). The mutations were reintroduced into the cut12.1 background to confirm that the cold-sensitive mutation did indeed compensate for the cut12.1 defect (Figure 1B). Generation of stable cut12.1/cut12.1 ade6.M210/ade6.M216 mat1.102/h- rotx.1/rotx+ heterozygous diploids established that all alleles selected for further characterization were recessive with respect to both suppression of cut12.1 and cold sensitivity (data not shown).

Figure 1.—

Cold-sensitive rot− mutants suppress the cut12.1 deficiency at 36°. The indicated strains were streaked (A and B) or spotted as serial dilutions (C) onto rich YES medium at the indicated temperatures.

Cloning of rot genes:

With the exception of rot5+, all rot genes were cloned by complementation of the cold-sensitive growth defect of rot alleles. As attempts to clone rot5+ by complementation of rot5.1 isolated the same DEAD box helicase gene dbp10+ as a multicopy suppressor in 98 separate transformants, we employed a strategy to generate a genomic library that lacked this gene. The pURB2 library (Barbet et al. 1992) was amplified in Escherichia coli, to generate around 5000 colonies on each of 44 plates. DNA was prepared separately from each plate and PCR identified 27 pools that contained the dbp10+ ORF. The remaining 17 pools were combined to create a library with a complexity of 85,000 [the complexity of the original library was 105,000 clones (Barbet et al. 1992)]. Transformation of this selected library into rot5.1 cells generated two colonies at restrictive temperature that contained the ORF SPBC32F12.15. Sequences adjacent to the gtb1+/tug1+ locus that lies 16.7 kb from ORF SPBC32F12.15 were used to integrate the LEU2+ gene adjacent to the gtb1+/tug1+ locus and subsequent crossing to rot5.1 established tight linkage (8.6 cM). Crossing rot5.1 to this LEU2+ marker gave no recombinants in over 200 random spores Sequencing the SPBC32F12.15 ORF identified a substitution of proline for alanine in the the fourth codon of the protein indicating that SPBC32F12.15 is indeed rot5+.

rot+ genes encode molecules that modulate protein production:

The rot+ genes and corresponding multicopy suppressors were predicted to encode molecules implicated in the control of protein production at the level of transcription, translation, or RNA processing (Table 2). The rot1/tfb2+ and rot5+/tfb5+ genes and a suppressor of rot4.1 (tfb1+) encoded conserved components of the TFIIH complex that plays a critical role in promoting cell-cycle-dependent transcription of a subset of S. pombe genes (Lee et al. 2005). This predicted functional relationship was supported by genetic interactions as rot1.1 (hereafter referred to as tfb2.rt1) displayed synthetic lethality with rot5.1 (hereafter referred to as tfb5.rt5) and the introduction of a multicopy plasmid harboring the tfb5+ gene was able to complement the cold sensitivity of tfb2.rt1 (Figure 1C). rot3+/pla1+ encodes the essential nuclear poly(A) polymerase (Ohnacker et al. 1996; Ding et al. 2000; Stevenson and Norbury 2006). rot4+ encoded the Rpl4301 component of the 60S ribosomal complex. A second rpl4302+ gene that differs by just four amino acids was isolated as a multicopy suppressor of rot4.1 (hereafter referred to as rpl4301.rt4). The rot2+ gene and multicopy suppressors of rot2.1 and tfb5.rt5 encode DEAD/DEAH box helicases.

TABLE 2.

Suppressors of rot mutants encode transcription and translation factors

| Mutant | Gene | Product | Biological function |

|---|---|---|---|

| tfb2.rt1 | tfb2+ | Transcription factor TFIIH complex | Transcription (E) |

| rot2.1 | rot2+ | DEAD/DEAH box helicase | RNA export (P) |

| pla1.rt3 | pla1+ | Poly(A) polymerase | RNA poly-adenylation (E) |

| rpl4301.rt4 | rpl4301 | 60S ribosomal protein | Translation (P) |

| tfb5.rt5 | tfb5+ | Transcription factor TFIIH complex | Transcription (P) |

| Mutant | aa identity to human homologs (%) | Multicopy suppressors |

|---|---|---|

| tfb2.rt1 | 45 | NF |

| rot2.1 | 47, 35, 29 | DEAD/DEAH box helicase SPBC13G1.10c |

| Pseudo C-terminal DNA helicase SPAC212.06c | ||

| pla1.rt3 | 47, 47, 46 | NF |

| rpl4301. rt4 | 58 | tfb1+ (TFIIH complex) |

| rpl4302+ | ||

| tfb5.rt5 | 25 | dbp10+ (DEAD/DEAH box helicase) |

P, predicted by sequence; E, experimental; NF, not found.

rot mutations alter size at division and spindle pole function:

Because cut12 alleles exhibit cell-cycle and spindle formation phenotypes, the microtubule cytoskeleton and length at division of rot mutants was assessed. With the exception of the rpl4301.rt4 mutant that showed no deviation from wild type after two generations at restrictive temperature, all rot mutations altered the number of cells in mitosis at any one time, the size at which cells committed to mitosis and increased the size and number of Sad1 foci at the nuclear periphery and the appearance of Sad1 foci at some distance from the chromatin. Importantly, three phenocopied cut12.1 in forming monopolar rather than bipolar spindles (Table 3 and Figures 2–4).

TABLE 3.

rot mutants phenotypes

| Mislocalization of Sad1

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length at mitosis (μm)

|

Interphase

|

Mitosis

|

||||

| Mutant | 36° | 20° | 36° | 20° | 36° | 20° |

| tfb2.rt1 | 11.7 ± 0.9 | 15.8 ± 1.6 | Yes | No | No | No |

| rot2.1 | 11.7 ± 2.6 | 12.4 ± 3.5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| pla1.rt3 | 9.3 ± 1.5 | 11.0 ± 1.5 | No | Yes | No | No |

| rpl4301.rt4 | 13.4 ± 1.7 | 14.0 ± 1.1 | No | No | No | No |

| tfb5.rt5 | 14.0 ± 1.4 | 17.0 ± 2.3 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| ded1-61 | 15.0 ± 1.2 | 17.1 ± 1.5 | No | Yes | No | No |

| wt | 13.9 ± 0.96 | 14.6 ± 1.5 | No | No | No | No |

| Cells in mitosis (%)

|

Monopolar spindles (%)

|

PAAs (%)

|

||||

| Mutant | 36° | 20° | 36° | 20° | 36° | 20° |

| tfb2.rt1 | 6 | 22 | No | 10 | 21 | 25 |

| rot2.1 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 38 | 8 | 34 |

| pla1.rt3 | 6 | 2 | No | No | 35 | 15 |

| rpl4301.rt4 | 8 | 7 | No | No | 15 | 14 |

| tfb5.rt5 | 7 | 15 | 14 | 30 | 3 | 15 |

| wt | 8 | 7 | No | No | 14 | 15 |

PAAs, post-anaphase arrays. n = 200.

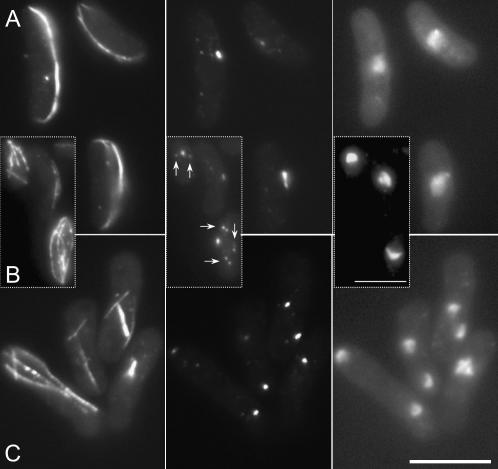

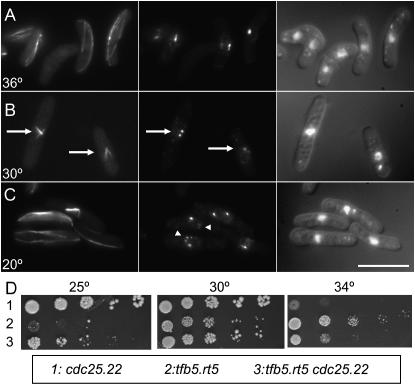

Figure 2.—

tfb2.rt1 mutants form monopolar spindles at the restrictive temperature. tfb2.rt1cells were grown to early log phase at 36° (A) before the temperature of the medium was changed to 20° (B). Immediately before and 24 hr after the shift cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence to reveal the distribution of microtubules (left), Sad1 protein (middle), and the relative location of the chromatin (right). Arrows indicate the two SPBs of a late mitotic spindle in a cell that is just forming a post-anaphase array even though chromosome segregation has not occurred. Bar, 10 μm.

Figure 3.—

The tfb5.rt5 mutation compromises spindle formation at 30°, increases the number of Sad1 foci on interphase nuclei at 20°, and compensates for the cdc25.22 growth defect at 34°. (A–C) tfb5.rt5 cells were grown to early log phase at 36° before the temperature of the medium was changed to 30° or 20°. Immediately before (A) and 12 hr after the shift to 30° (B) and 20 hr after the shift to 20° (C) cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence to reveal the distribution of microtubules (left), Sad1 protein (middle), and the relative location of the chromatin (right). Arrows in B indicate monopolar spindles, while arrowheads in C point to multiple Sad1 foci on an interphase nucleus. We assume that the largest of these foci is the SPB. Bar, 10 μm. (D) Spot tests of serial dilutions show that the tfb5.rt5 cdc25.22 strain grows more efficiently than either single mutant at 34° or 25°, respectively.

Monopolar spindles were associated with chromosome segregation errors in both TFIIH components identified in the screen; tfb2.rt1 cells had monopolar spindles at 20°, while tfb5.rt5 phenocopied the cut12.1 monopolar phenotype at the semipermissive temperature of 30° but not at the restrictive 20° (Figures 2B, 3B, and 3C; Table 3). At the permissive temperature of 36° tfb5.rt5 cells exhibited a range of morphogenetic defects including cell bending to generate the ban− phenotype (Figure 3A) (Verde et al. 1995).

The proportion of the population of rot2.1 cells that formed monopolar spindles was also influenced by the culture temperature as 5% of all mitoses at 36° had monopolar spindles whereas 38% have monopolar spindles at 18° (Figure 4, A, C, and D; Table 3). The rot2.1 mutation had a further impact upon spindle architecture as there was a marked proliferation of Sad1 foci around the periphery nuclei and some dots seen away from the chromatin of rot2.1 cells at both the restrictive and permissive temperature (Figure 4, A–D, data not shown). This alteration in Sad1 distribution was not always associated with the formation of a monopolar spindle (Figure 4, A and B). Furthermore, the distribution of the core SPB components Cut12 and Sid4 was not affected by the rot2.1 mutation (Figure 4, E and F, data not shown). Thus the excess Sad1 foci neither acted as spindle poles nor contained all SPB components. The radical changes in Sad1 distribution were not mirrored by a significant enhancement of protein levels (Figure 4G), suggesting that the rot2.1 mutation affected the recruitment of Sad1 protein to sites on the nuclear envelope. rot2.1 cells divided at reduced cell size and had alterations in the control of the final stages of cytokinesis because there were fewer cells with two separated nuclei and post-anaphase arrays of microtubules at the permissive temperature (8% vs. 15% for wild-type control), yet more at the restrictive (34% vs. 14% for wild-type control; Table 3).

pla1.rt3 mutant phenotype resembled that of rot2.1 except that cells did not form monopolar spindles. Cell length at division was decreased, and there was a proliferation of Sad1 foci without an obvious increase in Sad1 protein levels (Figures 5 and 4G) and an accumulation of cells with post-anaphase microtubule arrays (35% at permissive; Table 3). While the figure of 15% post-anaphase arrays seen at the restrictive is reminiscent of the wild-type value of 14%, the proportion of cells in the preceding phase of the cell cycle (those with mitotic spindles) was radically reduced (2% vs. 7%) (Table 3; Figure 5). As a reduction in the numbers of spindles should similarly reduce the number of cells in subsequent stages of the cell cycle, the data suggest that pla1.rt3 also delays the completion of cell fission at the restrictive temperature.

Figure 5.—

pla1.rt3 mutants display multiple Sad1 foci around their nuclear periphery. pla1.rt3 cells were grown to early log phase at 36° (A) before the temperature of the medium was changed to 20° (B). Immediately before and 12 hr after the shift cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence to reveal the distribution of microtubules (left), Sad1 protein (middle), and the relative location of the chromatin (right). Bar, 10 μm.

Similarities between ded1/sum3− and rot− phenotypes:

As the current screen established that DEAD box helicases exhibited genetic interactions with a cdc25.22 suppressor, and the DEAD box helicase Ded1/Sum3 has been linked to Cdc25 and Cdc2 function in mitotic control (Forbes et al. 1998; Grallert et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2002), we assessed the status of the microtubule cytoskeleton in ded1.61 cells. These cold-sensitive cells were incubated at 18° for 12 hr before processing to reveal the microtubule cytoskeleton and chromatin. The length at which cells entered mitosis increased (Table 3) and multiple Sad1 foci accumulated around the interphase nuclei and away from the chromatin of bent cells in which microtubules curled around cell tips (Figure 6). The increase in the number of Sad1 foci was not accompanied by a radical change in Sad1 levels (Figure 4G). The similarity of these phenotypes to those of the rot mutants prompted us to ask whether multicopy levels of ded1+ could mimic the DEAD/DEAH box helicases identified in this study in suppressing cut12.1; however, it could not. Second we asked whether the incorporation of ded1.61 alongside cut12.1 in the same cell mimicked the rot mutants in suppressing the lethality of cut12.1 at 36°; however, the double mutant was synthetically lethal at both 30° and 36°. A potential overlap between ded1+ and rot genes was revealed by the inviability of tfb5.rt5 ded1.61 double mutants at 36° that is normally permissive for either mutant.

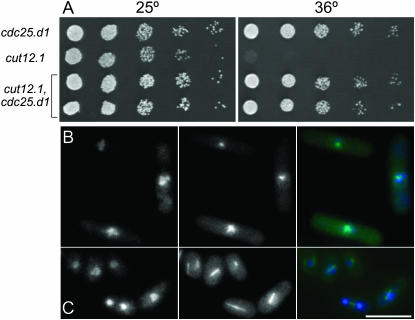

cdc25.d1 suppresses cut12.1:

One model to account for the identification of molecules that have the potential to modulate the abundance of proteins in a screen for cut12.1 suppressors is that they altered the levels of molecules related to Cut12 function and so enabled the compromised version of Cut12.1 to perform the essential function executed by the wild-type molecule sufficiently well for the cells to survive. As Cut12 modulates pathways that control entrance to mitosis and both Cdc25 and B-type cyclins are exquisitely sensitive to changes in translational control (Daga and Jimenez 1999; Grallert et al. 2000), we asked whether elevating the levels of Cdc25 or the major B-type cyclin (Fisher and Nurse 1996), Cdc13, would suppress cut12.1.

Cdc13 levels were elevated by inducing the gene on a multicopy plasmid while Cdc25 levels were enhanced by integrating the cdc25.d1 allele at the leu1 locus under the control of the nmt1+ promoter. The removal of three pseudo-ORFs in the 5′ region of the cdc25+ UTR greatly increases the amount of the phosphatase that is produced from the mutant cdc25.d1 gene (Daga and Jimenez 1999). Increasing cdc13+ dosage did not suppress cut12.1; however, the introduction of the cdc25.d1 allele did (Figure 7A). In time lapse microscopy of strains harboring the tubulin–GFP fusion gene atb2.GFP, only 4 of 31 cut12.1 cells formed bipolar mitotic spindles and completed division (Figure 7B), while 29 of 37 cut12.1 cdc25.d1 mutants successfully completed mitosis (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.—

cdc25.d1 suppresses cut12.1 (A) Spot tests of serial dilutions of the indicated strains on rich YES medium at the indicated temperatures. (B and C) Frames from movies of cut12.1 atb2.gfp and cdc25.d1 cut12.1 atb2.gfp cells undergoing the typical monopolar defective mitoses of cut12.1 cells (B), or bipolar divisions of cut12.1 cells in which the mitotic defect is compensated for by the inclusion of the cdc25.d1 mutation. The hyperactivity conferred by the enhanced translation of the cdc25.d1 allele accelerates mitotic commitment and so reduces cell length at commitment to mitosis (Daga and Jimenez 1999).

A further link between the cut12 and cdc25 emerged when we asked whether any of the rot genes exhibited a genetic interaction with cdc25.22 as tbf5.rt52 cdc25.22 double mutants were healthier at 25° than rot5.2 and healthier at 34° than cdc25.22 (Figure 3D).

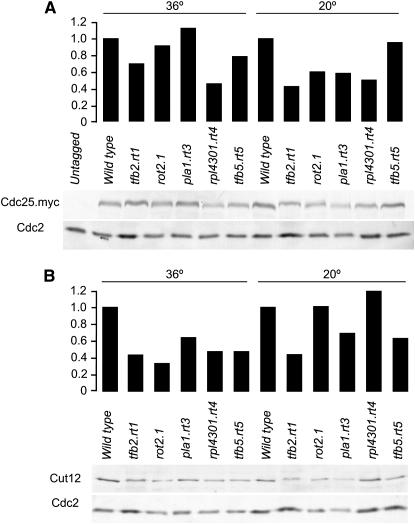

rot mutations reduce the levels of Cdc25 and Cut12:

The finding that alteration of the levels of a key mitotic inducer suppressed the conditional lethality of cut12.1 prompted us to ask whether this formed the basis of the suppression of cut12.1 by these mutations. We therefore generated strains that combined the cdc25.myc allele (Lopez-Girona et al. 1999) alongside each rot mutant and blotted extracts to relate the amount of Cdc25.myc to a standard loading control, Cdc2 (Simanis and Nurse 1986) (Figure 8A). The relative levels of Cdc25.myc were reduced below those seen in wild-type cells in all rot mutant backgrounds at either the permissive temperature of 36°, which suppresses cut12.1 (tfb5.rt5), or at 20°, which is restrictive for the function of the respective Rot molecules (rot2.1, pla1.rt3) or at both (rpl4301.rt4, tfb2.rt1) (Figure 8A). Similarly, the relative levels of Cut12 were reduced below those of wild-type cells in all rot mutants at 36° and in tfb2.rt1, pla1.rt3, and tfb5.rt5 at 20° (Figure 8B). Thus, while elevation of a mitotic inducer is sufficient to suppress Cut12, the suppression in the different rot mutant backgrounds does not appear to involve elevation of either Cdc25 or Cut12 levels.

Figure 8.—

Cdc25 and Cut12 levels decrease in rot mutants. Wild-type and single rot mutants (B) or rot mutants that also harbored the cdc25.myc allele (A) were grown to midlog phase at the permissive temperature of 36° or to early log phase and shifted to 20° for 15 hr as indicated before extracts were prepared and blotted with the 9E10 monoclonal antibody that recognized the myc epitope on Cdc25.myc or polyclonal antibodies that recognized Cut12 or Cdc2 proteins. As Cdc2 migrated lower down each respective gel the blots are from the same gels as the top panels and act as loading controls. The intensity of the bands was quantified and the Cdc25.myc and Cut12 bands were normalized to the relevant Cdc2 loading control to give the relative levels that are shown in the graphs above the blots.

DISCUSSION

We have used a genetic approach to identify molecules whose function can be altered to compensate for the loss of Cut12 function in the cut12.1 mutant. To facilitate the subsequent phenotypic analyses of these mutants we selected those in which the mutation both suppressed the cut12.1 temperature sensitivity and blocked growth at 20°. All five loci encoded molecules that are likely to influence protein levels. While it is possible that suppression arises simply from the production of more of a defective cut12.1 protein or by readthrough of the premature stop codon in the cut12.1 allele (Bridge et al. 1998), the monopolar spindle phenotypes arising from mutation of three of the five rot genes favor an intimate involvement of rot gene products in commitment to mitosis.

In testing the simple hypothesis that the rot mutants suppressed cut12.1 because they altered the balance of mitotic inducers we found that elevation of Cdc25 levels suppressed the temperature sensitivity of cut12.1. Thus, not only do cdc25.22 mutations exacerbate the spindle formation defect of cut12.1 (Bridge et al. 1998) and hyperactivating cut12.s11 mutations suppress deletion of cdc25+ (Hudson et al. 1990, 1991), but also hyperactivating mutations in cdc25+ suppress loss-of-function mutations in cut12+. Such reciprocal relationships strongly suggest that the spindle formation defect of cut12.1 arises from a defect in cell-cycle control rather than an error in the nucleation of microtubules or some other physical aspect of spindle architecture.

This notion that a monopolar spindle phenotype can be indicative of a weak attempt at mitotic commitment would explain the impact of mutation of wee1 upon frequency of monopolar spindles in conditional fin1 mutants. Fin1 kinase plays a critical role in regulating mitotic commitment that is related to Cut12 and Cdc25 function. The fin1.A5 mutation results in monopolar spindles in which only one of two SPB functions in 80% of cells at the 37° (Grallert and Hagan 2002). Significantly the number of monopolar, defective, mitoses is halved by simply reducing the constraints for mitotic entry by abolishing Wee1 function (Grallert and Hagan 2002). Given that genetic evidence argues that the only function of the “wee1 cdc25 switch” is to control the timing of MPF activation by modulating the phosphorylation status of tyrosine 15 of Cdc2 (Fantes 1979; Russell and Nurse 1987a; Gould and Nurse 1989), these data strongly support the notion that the fin1 monopolar phenotype (like that of cut12.1) arises from defective activation of MPF during mitotic commitment.

If a monopolar spindle phenotype is indicative of a compromised commitment to mitosis, it could explain why monopolar spindles occur as a consequence of compromised TFIIH function as it was recently established that TFIIH modulates the cell-cycle levels of transcripts of mitotic inducers prior to mitosis (Lee et al. 2005). Compromising TFIIH activity would reduce the ability to regulate mitotic inducers to promote an efficient entrance to mitosis. Similar arguments could account for why a compromised poly(A) polymerase could reduce the ability to accumulate sufficient transcripts to get into mitosis. It is currently unclear which of the many candidate cell-cycle regulators could be altered to engender the suppression of cut12.1 in the rot mutants. Cdc25 and Cut12 levels are actually reduced by mutation of rot mutants, making these unlikely candidates; however, it is distinctly possible that the levels of the range of inhibitory regulators including Nim1/Cdr1 or Wee1 (Russell and Nurse 1987a,b; Young and Fantes 1987) may be reduced or that mitotic inducers other than Cdc25 or Cut12, such as components of the stress response pathway (Shiozaki and Russell 1995; Petersen and Hagan 2005), or molecules that impinge upon the stress response pathway, may be elevated. The identification of candidate molecules requires whole proteome analyses that are beyond the scope of the current study; however, the principle established by this study that overproduction of a mitotic inducer suppresses the monopolar spindle formation phenotype of cut12.1 extends our understanding of mitotic control.

While the intimate relationship between cut12 and cdc25 indicates that Cut12 is a key cell-cycle regulator, the impact of the cut12.1 mutation upon SPB function is unilateral rather than bilateral as one becomes active while the other lies dormant or is defective. This indicates that while Cut12 can influence the global decision to commit to mitosis, it must also act at a local level to activate individual SPBs and that the two SPBs differ in their ability to respond to this second, local, function. Such disparity could arise because SPB duplication is conservative (Grallert et al. 2004) and the SPB that forms in the cell cycle after the shift to the restrictive temperature is nonfunctional. Alternatively, mitotic commitment could resemble the controls of the septum initiation network (SIN) in which the SIN is activated on the new and not the old SPB during anaphase B (Sohrmann et al. 1998; Grallert et al. 2004). In this scenario only one of the two SPBs in a cut12.1 mutant can become active because it is the only one that is mature enough to do so. In the same vein the reason that the spindle defect in Fin1 mutants is halved by abolishing Wee1 function (Grallert and Hagan 2002) may also lie in a quantum difference in the response of one SPB over the other.

An interesting feature of SPB structure and function that has been revealed by the rot and ded1 mutations is the proliferation of Sad1 foci. This increase in Sad1 foci is not a general feature of all SPB components in these mutants as both core SPB components Cut12 and Sid4 (Bridge et al. 1998; Chang and Gould 2000) remained as the single or double foci expected of SPB markers while Sad1 foci proliferated. This suggests that Sad1 plays a more peripheral role in SPB function that would be in line with the function of other members of SUN domain family proteins in higher eukaryotes where these molecules anchor centrosomes to the nuclear envelope (Tzur et al. 2006). A peripheral role in SPB function is also consistent with inability of excess wild-type Sad1 to alter spindle function (Hagan and Yanagida 1995). Furthermore, in the monopolar spindles of both Fin1 and Cut12 mutants Sad1 is often missing from the active SPB but accumulates on the nonfunctional SPB (Bridge et al. 1998; Grallert and Hagan 2002). Thus, Sad1 appears to be a peripheral SPB component that has an affinity for elements within the nuclear envelope and some level of control normally limits the amount of Sad1 incorporated into the nuclear envelope alongside the SPB. The precise nature of this control remains obscure; however, it may simply be a case of provision of the right amount of a docking protein because changes in diverse molecules that modulate transcription and translation we describe here all enhance the number of Sad1 foci on the nuclear periphery, while not causing gross alterations the levels of Sad1 itself.

While translational control and cell-cycle control have been linked at a variety of levels and it is well established that the abundance of a number of molecules oscillates as cells progress through the cell cycle, we still know relatively little about how the large number of fluctuations that have been recorded combine to determine the timing of cell-cycle transitions (Mitchison 2003). Extensive work in many systems, but principally budding yeast, have established that in all eukaryotes, signaling from the TOR pathway ensures the appropriate coupling between nutrient supply, growth, and the transition of key cell-cycle transitions (Wullschleger et al. 2006). In fission yeast the stress-response pathway also plays a critical role in coupling cell-cycle and differentiation decisions to nutritional status (Shiozaki and Russell 1995; Petersen and Hagan 2005). In addition a number of genetic screens designed to identify genes that would influence cell-cycle transitions in, for example, our current study, have identified mutations in molecules that modulate protein levels (Forbes et al. 1998; Daga and Jimenez 1999; Grallert et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2002). The frequency with which these screens and those for mitotic mutants in Drosophila (Girdham and Glover 1991; Leonard et al. 2003) identify DEAD box helicases highlight the critical roles that RNA processing/translational control plays in modulating cell-cycle progression (Cordin et al. 2005).

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Bagley in the Paterson Institute Advanced Imaging Facility and Esther Jolley for technical assistance, Ged Brady for instruction on the customization of gene libraries, Keith Gull, Juan Jimenez, and Kayoko Tanaka for reagents, and Roger Tsien for Tdtomato fluorescent protein. Funding was supported by Cancer Research UK (CRUK).

References

- Abrieu, A., T. Brassac, S. Galas, D. Fisher, J. C. Labbe et al., 1998. The polo-like kinase Plx1 is a component of the MPF amplification loop at the G2/M-phase transition of the cell cycle in Xenopus eggs. J. Cell Sci. 111: 1751–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, N., W. J. Muriel and A. M. Carr, 1992. Versatile shuttle vectors and genomic libraries for use with Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene 114: 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, C. R., S. H. Woo, Y. S. Chung, C. Jones and C. F. Hardy, 2001. Cdc5 interacts with the Wee1 kinase in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 4949–4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booher, R., and D. Beach, 1988. Involvement of cdc13+ in mitotic control in Schizosaccharomyces pombe: possible interaction of the gene-product with microtubules. EMBO J. 7: 2321–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, A. J., M. Morphew, R. Bartlett and I. M. Hagan, 1998. The fission yeast SPB component Cut12 links bipolar spindle formation to mitotic control. Genes Dev. 12: 927–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L., and K. L. Gould, 2000. Sid4p is required to localize components of the septum intiation pathway to the spindle pole body in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 5249–5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordin, O., J. Banroques, N. K. Tanner and P. Linder, 2005. The DEAD-box protein family of RNA helicases. Gene 367: 17–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creanor, J., and J. M. Mitchison, 1994. The kinetics of H1 kinase activation during the cell cycle of wild type and wee mutants of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 107: 1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daga, R. R., and J. Jimenez, 1999. Translational control of the Cdc25 cell cycle phosphatase: a molecular mechanism coupling mitosis to cell growth. J. Cell Sci. 112: 3137–3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.-Q., Y. Tomita, A. Yamamoto, Y. Chikashige, T. Haraguchi et al., 2000. Large-scale screening of intracellular protein localization in living fission yeast by the use of GFP-fusion genomic DNA library. Genes Cells 5: 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan, G. I., G. K. Lewis, G. Ramsay and J. M. Bishop, 1985. Isolation of monoclonal-antibodies specific for human c-myc proto-oncogene product. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5: 3610–3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, T., E. T. Rosenthal, J. Youngblom, D. Distel and T. Hunt, 1983. Cyclin: a protein specified by maternal mRNA in sea urchin eggs that is destroyed at each cleavage division. Cell 33: 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantes, P., 1979. Epistatic gene interactions in the control of division in fission yeast. Nature 279: 428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantes, P. A., 1983. Control of timing of cell-cycle events in fission yeast by the wee1+ gene. Nature 302: 153–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, C., and P. Russell, 1991. Fission yeast p107wee1 mitotic inhibitor is a tyrosine/serine kinase. Nature 349: 808–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D. L., and P. Nurse, 1996. A single fission yeast mitotic cyclin-B p34Cdc2 kinase promotes both S-Phase and mitosis in the absence of G1 cyclins. EMBO J. 15: 850–860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, K. C., T. Humphrey and T. Enoch, 1998. Suppressors of cdc25p overexpression identify two pathways that influence the G2/M checkpoint in fission yeast. Genetics 150: 1361–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdham, C. H., and D. M. Glover, 1991. Chromosome tangling and breakage at anaphase result from mutations in Lodestar, a Drosophila gene encoding a putative nucleoside triphosphate-binding protein. Genes Dev. 5: 1786–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould, K. L., and P. Nurse, 1989. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the fission yeast Cdc2+ protein-kinase regulates entry into mitosis. Nature 342: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grallert, A., and I. M. Hagan, 2002. Schizosaccharomyces pombe NIMA-related kinase Fin1 regulates spindle formation and an affinity of Polo for the SPB. EMBO J. 21: 3096–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grallert, A., A. Krapp, S. Bagley, V. Simanis and I. M. Hagan, 2004. Recruitment of NIMA kinase shows that maturation of the S. pombe spindle-pole body occurs over consecutive cell cycles and reveals a role for NIMA in modulating SIN activity. Genes Dev. 18: 1007–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grallert, B., S. E. Kearsey, M. Lenhard, C. R. Carlson, P. Nurse et al., 2000. A fission yeast general translation factor reveals links between protein synthesis and cell cycle controls. J. Cell. Sci. 113(8): 1447–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, I., and M. Yanagida, 1995. The product of the spindle formation gene sad1+ associates with the fission yeast spindle pole body and is essential for viability. J. Cell Biol. 129: 1033–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T., S. Funahashi, T. Uemura and M. Yanagida, 1986. Isolation and characterization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe cut mutants that block nuclear division but not cytokinesis. EMBO J. 5: 2973–2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, I., P. R. Clarke, M. J. Marcote, E. Karsenti and G. Draetta, 1993. Phosphorylation and activation of human cdc25-C by cdc2-cyclin B and its involvement in the self amplification of MPF at mitosis. EMBO J. 12: 53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, J. D., H. Feilotter and P. G. Young, 1990. stf1: non-wee mutations epistatic to cdc25 in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 126: 309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, J. D., H. Feilotter, C. Lingner, R. Rowley and P. Young, 1991. stf1: a new supressor of the mitotic control gene cdc25 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 56: 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi, T., and J. L. Maller, 1993. Elimination of cdc2 phosphorylation sites in the cdc25 phosphatase blocks initiation of M-phase. Mol. Biol. Cell 4: 1337–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi, T., and J. Maller, 1995. Phosphorylation and activation of Xenopus Cdc25 phosphatase in the absence of Cdc2 and Cdk2 kinase activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 6: 215–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman, M., C. Lindon, E. A. Nigg and J. Pines, 2003. Active cyclin B1-Cdk1 first appears on centrosomes in prophase. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaiskou, A., C. Jessus, T. Brassac and R. Ozon, 1999. Phosphatase 2A and Polo kinase, two antagonistic regulators of Cdc25 activation and MPF auto-amplification. J. Cell Sci. 112: 3747–3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaiskou, A., A. C. Lepretre, G. Pahlavan, D. Du Pasquier, R. Ozon et al., 2004. Polo-like kinase confers MPF autoamplification competence to growing Xenopus oocytes. Development 131: 1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, J. B., and J. D. Boeke, 1994. Efficient targeted integration at leu1-32 and ura4-294 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 136: 849–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovelman, R., and P. Russell, 1996. Stockpiling of Cdc25 during a DNA-replication checkpoint arrest in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai, A., and W. G. Dunphy, 1996. Purification and molecular-cloning of Plx1, a Cdc25-regulatory kinase from Xenopus egg extracts. Science 273: 1377–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, H. A., and E. A. Nigg, 1996. Antibody microinjection reveals an essential role for human polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in the functional maturation of mitotic centrosomes. J. Cell Biol. 135: 1701–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. M., I. Miklos, H. Du, S. Watt, Z. Szilagyi et al., 2005. Impairment of the TFIIH-associated CDK-activating kinase selectively affects cell cycle-regulated gene expression in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 16: 2734–2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, D., P. Ajuh, A. L. Lamond and R. J. Legerski, 2003. hLodestar/HuF2 interacts with CDC5L and is involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308: 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Y., B. S. Nefsky and N. C. Walworth, 2002. The Ded1 DEAD box helicase interacts with Chk1 and Cdc2. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 2637–2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Girona, A., B. Furani, O. Mondesert and P. Russell, 1999. Nuclear localisation of Cdc25 is regulated by DNA damage and a 14–3-3 protein. Nature 397: 172–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIver, F. H., K. Tanaka, A. M. Robertson and I. M. Hagan, 2003. Physical and functional interactions between polo kinase and the spindle pole component Cut12 regulate mitotic commitment in S. pombe. Genes Dev. 17: 1507–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, C. H., and P. Russell, 1993. Human Wee1 kinase inhibits cell division by phosphorylating p34cdc2 exclusively on Tyr15. EMBO J. 12: 75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison, J. M., 2003. Growth during the cell cycle. Int. Rev. Cytol. 226: 165–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, S., A. Klar and P. Nurse, 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194: 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, P. R., T. R. Coleman and W. G. Dunphy, 1995. Cell-cycle regulation of a Xenopus Wee1-like kinase. Mol. Biol. Cell 6: 119–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill, D. P., J. Petersen, H. Ohkura, D. M. Glover and I. M. Hagan, 1999. Plo1 kinase recruitment to the spindle pole body and its role in cell division in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 2771–2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, P., 1990. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature 344: 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnacker, M., L. Minvielle-Sebastia and W. Keller, 1996. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe pla1 gene encodes a poly(A) polymerase and can functionally replace its Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 2585–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L. L., and H. Piwnicaworms, 1992. Inactivation of the p34cdc2cyclinB complex by the human Wee1 tyrosine kinase. Science 257: 1955–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J., and I. M. Hagan, 2005. Polo kinase links the stress pathway to cell cycle control and tip growth in fission yeast. Nature 435: 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, P., and P. Nurse, 1986. Cdc25+ functions as an inducer in the mitotic control of fission yeast. Cell 45: 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, P., and P. Nurse, 1987. a Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein- kinase homolog. Cell 49: 559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, P., and P. Nurse, 1987. b The mitotic inducer nim1+ functions in a regulatory network of protein-kinase homologs controlling the initiation of mitosis. Cell 49: 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakchaisri, K., S. Asano, L. R. Yu, M. J. Shulewitz, C. J. Park et al., 2004. Coupling morphogenesis to mitotic entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 4124–4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki, K., and P. Russell, 1995. Cell-cycle control linked to extracellular environment by MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Nature 378: 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simanis, V., and P. Nurse, 1986. The cell-cycle control gene cdc2+ of fission yeast encodes a protein-kinase potentially regulated by phosphorylation. Cell 45: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrmann, M., S. Schmidt, I. Hagan and V. Simanis, 1998. Asymmetric segregation on spindle poles of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe septum-inducing protein kinase Cdc7p. Genes Dev. 12: 84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, A. L., and C. J. Norbury, 2006. The Cid1 family of non-canonical poly(A) polymerases. Yeast 23: 991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z. H., T. R. Coleman and W. G. Dunphy, 1993. Two distinct mechanisms for negative regulation of the wee1 protein- kinase. EMBO J. 12: 3427–3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzur, Y. B., K. L. Wilson and Y. Gruenbaum, 2006. SUN-domain proteins: ‘Velcro’ that links the nucleoskeleton to the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7: 782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verde, F., J. Mata and P. Nurse, 1995. Fission yeast-cell morphogenesis: identification of new genes and analysis of their role during the cell-cycle. J. Cell Biol. 131: 1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, N., H. Arai, Y. Nishihara, M. Taniguchi, N. Watanabe et al., 2004. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquintination of somatic Wee1 by SCFβ-TrCP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 4419–4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, A., T. Sherwin, R. Sasse, T. H. Macrae, A. J. Baines et al., 1989. Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal-antibodies. J. Cell Sci. 93: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger, S., R. Loewith and M. N. Hall, 2006. TOR signalling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124: 471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, P. G., and P. A. Fantes, 1987. Schizosaccharomyces pombe mutants affected in their division response to starvation. J. Cell Sci. 88: 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., Y. Zhao, Z. Li, S. Galas and M. L. Goldberg, 2006. Greatwall kinase participates in the CDC2 autoregulatory loop in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol. Cell 22: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]