Abstract

Many biochemical approaches show functions of calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) in abscisic acid (ABA) signal transduction, but molecular genetic evidence linking defined CDPK genes with ABA-regulated biological functions at the whole-plant level has been lacking. Here, we report that ABA stimulated two homologous CDPKs in Arabidopsis thaliana, CPK4 and CPK11. Loss-of-function mutations of CPK4 and CPK11 resulted in pleiotropic ABA-insensitive phenotypes in seed germination, seedling growth, and stomatal movement and led to salt insensitivity in seed germination and decreased tolerance of seedlings to salt stress. Double mutants of the two CDPK genes had stronger ABA- and salt-responsive phenotypes than the single mutants. CPK4- or CPK11-overexpressing plants generally showed inverse ABA-related phenotypes relative to those of the loss-of-function mutants. Expression levels of many ABA-responsive genes were altered in the loss-of-function mutants and overexpression lines. The CPK4 and CPK11 kinases both phosphorylated two ABA-responsive transcription factors, ABF1 and ABF4, in vitro, suggesting that the two kinases may regulate ABA signaling through these transcription factors. These data provide in planta genetic evidence for the involvement of CDPK/calcium in ABA signaling at the whole-plant level and show that CPK4 and CPK11 are two important positive regulators in CDPK/calcium-mediated ABA signaling pathways.

INTRODUCTION

The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) regulates many processes of plant growth and development, such as seed maturation and germination, seedling growth, flowering, and stomatal movement, and is a key hormone mediating plant adaptation to various environmental challenges, including drought, salt, and cold stress (reviewed in Koornneef et al., 1998; Leung and Giraudat, 1998; Finkelstein and Rock, 2002). Three ABA receptors have been identified: FCA, which is involved in the control of flowering time (Razem et al., 2006), and ABAR and GCR2, which regulate seed germination, seedling growth, and stomatal movement (Shen et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007). Numerous cellular components that modulate ABA responses also have been characterized (reviewed in Finkelstein et al., 2002; Himmelbach et al., 2003; Fan et al., 2004). However, many ABA signaling components remain to be discovered.

Calcium plays an essential role in plant cell signaling (Hepler, 2005) and has been shown to be an important second messenger involved in ABA signal transduction (reviewed in Finkelstein et al., 2002; Himmelbach et al., 2003; Fan et al., 2004). Calcium signaling is modulated by specific calcium signatures (i.e., specific patterns in the amplitude, duration, location, and frequency of cytosolic free Ca2+ spikes in response to different stimuli). Specific calcium signatures are recognized by different calcium sensors to transduce calcium-mediated signals into downstream events (Sanders et al., 1999; Harmon et al., 2000; Rudd and Franklin-Tong, 2001). Plants have several classes of calcium sensor proteins, including calmodulin (CaM) and CaM-related proteins (Zielinski, 1998; Snedden and Fromm, 2001; Luan et al., 2002), calcineurin B-like (CBL) proteins (Luan et al., 2002), and calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) (Harmon et al., 2001; Cheng et al., 2002). The CBL-interacting protein kinase CIPK15 interacts with two calcium-modulated protein phosphatases 2C, ABI1 and ABI2 (Guo et al., 2002), which are well-characterized negative regulators of ABA signaling (Leung et al., 1994, 1997; Meyer et al., 1994; Sheen, 1998; Gosti et al., 1999; Merlot et al., 2001). CIPK15, and its homologs CIPK3 and CBL9, negatively regulate ABA signaling (Guo et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2003; Pandey et al., 2004). An AP2 transcription factor, At ERF7, that negatively regulates ABA response was shown to be a kinase substrate of CIPK15 (Song et al., 2005), suggesting that CIPK15 may regulate ABA signaling directly by phosphorylating a transcription factor and modulating gene expression.

CDPKs, which are the best-characterized calcium sensors in plants, are Ser/Thr protein kinases that have an N-terminal kinase domain joined to a C-terminal CaM-like domain via a junction region that serves to stabilize and maintain the kinase in an auto-inhibited state (Harper et al., 1991, 1994; Harmon et al., 2001; Cheng et al., 2002). CDPKs are encoded by a large multigene family with possible redundancy and/or diversity in their functions (Harmon et al., 2001; Cheng et al., 2002). Growing evidence indicates that CDPKs regulate many aspects of plant growth and development as well as plant adaptation to biotic and abiotic stresses (Bachmann et al., 1995, 1996; McMichael et al., 1995; Pei et al., 1996; Sheen, 1996; Li et al., 1998; Sugiyama et al., 2000; Romeis et al., 2001; Hrabak et al., 2003; Shao and Harmon, 2003; McCubbin et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2005; Ivashuta et al., 2005; Mori et al., 2006). In plant hormone signaling, CDPKs are believed to be important regulators involved in various signaling pathways (Cheng et al., 2002; Ludwig et al., 2004). Constitutive ectopic expression of two Arabidopsis thaliana CDPKs, CPK10/CDPK1 (Arabidopsis gene identifier number At1g74740), and CPK30/CDPK1a (At1g18890) in maize (Zea mays) leaf protoplasts activated a stress- and ABA-inducible promoter, showing the connection of CDPKs to ABA signaling (Sheen, 1996). An Arabidopsis CDPK, CPK32, was shown to interact with the ABA-induced transcription factor ABF4, and constitutive overexpression of CPK32 resulted in ABA-hypersensitive phenotypes in ABA-induced inhibition of seed germination (Choi et al., 2005). However, molecular genetic evidence via gene disruption is needed to unequivocally link defined CDPK genes with ABA-regulated biological functions, such as seed maturation and germination, seedling growth, stomatal movement, and plant stress tolerance. The Arabidopsis CDPKs CPK3 and CPK6 have been identified through gene knockout mutation as players in ABA-regulated stomatal signaling, but ABA-induced phenotypes in seed germination or postgermination growth were not observed in the loss-of-function mutants of these two CDPK genes, and alteration in plant tolerance to environmental stresses associated with ABA signaling due to the gene disruption of the two CDPKs was not reported (Mori et al., 2006). The Arabidopsis CDPK gene family includes 34 members (Cheng et al., 2002). Redundancies in the functions of CDPK genes are believed to hamper functional genetic analysis of these CDPKs.

We previously identified an ABA-stimulated CDPK, ACPK1, from grape berry (Vitis vinifera), which may be involved in ABA signaling (Yu et al., 2006, 2007). We worked in Arabidopsis to explore the biological functions of the two closest homologs of ACPK1, CPK4 and CPK11 (see Yu et al., 2006), in ABA signaling pathways. Here, we report that CPK4 and CPK11 are positive regulators in CDPK/calcium-mediated ABA signaling processes involving seed germination, seedling growth, guard cell regulation, and plant tolerance to salt stress, providing in planta genetic evidence for the modulation of CDPK/calcium in ABA signal transduction at the whole-plant level.

RESULTS

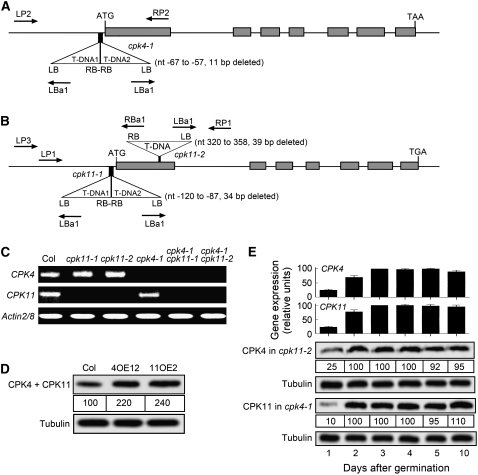

Identification of T-DNA Insertion Mutants and Overexpression Lines and Expression Profile of CPK4 and CPK11

We isolated from the pool of T-DNA insertion mutants in the ABRC the CPK4 mutant cpk4-1 (SALK_081860) and two different CPK11 mutant lines, cpk11-1 (SALK_023086) and cpk11-2 (SALK_054495). The cpk4-1 mutant harbors a tandem two-copy T-DNA insertion in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) upstream of exon 1 of the CPK4 gene (Figure 1A; see Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 and Supplemental Table 1 online). The tandem T-DNAs were inserted into the genome in an inverted fashion at the same locus, which generates an 11-bp deletion from −67 to −57 bp 5′ upstream of the translation start codon (Figure 1A; see Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 and Supplemental Table 1 online). The cpk11-1 mutant also harbors a tandem two-copy T-DNA insertion in an inverted fashion at the same locus in the 5′ UTR upstream of exon 1 of CPK11, generating a 34-bp deletion from −120 to −87 bp 5′ upstream of the translation start codon (Figure 1B; see Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 and Supplemental Table 1 online). A single copy of T-DNA was inserted into the genome of the cpk11-2 mutant, generating a 39-bp deletion from 320 to 358 bp downstream of the translation start codon (Figure 1B; see Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 and Supplemental Table 1 online). The genetic background for all the mutants is ecotype Columbia (Col). The three insertions were identified by PCR analysis of the Arabidopsis genome (Figures 1A and 1B; see Supplemental Figure 1 online) by sequencing of the genomic PCR products (see Supplemental Table 1 online) and by genomic DNA gel blot analysis, which helped to determine the number of T-DNA inserts (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). In addition to these assays, tandem T-DNA insertion at the same genomic locus in the cpk4-1 and cpk11-1 mutants was supported by genetic segregation analysis. The segregation assay for the nptII gene was performed by selecting for growth on medium containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) with seeds from heterozygous cpk4-1 and cpk11-1 mutants. The ratio of the resistant to sensitive plants was ∼3:1. Also, we obtained 30 plants (1/16) of the homologous cpk4-1 cpk11-1 double mutants from a population of 512 F2 plants from a cross of the cpk4-1 with the cpk11-1 single mutant. These results demonstrated that the T-DNAs have segregated as one locus, and the cpk4-1 and cpk11-1 are single-locus T-DNA insertion mutants.

Figure 1.

Molecular Analysis of T-DNA Insertion Mutants and CPK4- and CPK11-Transgenic Lines.

(A) T-DNA insertion site in cpk4-1 (Col ecotype; SALK_081860 from ABRC). Tandem T-DNA of two copies was inserted into the genome in an inverted fashion at the same locus, which generates an 11-bp deletion from −67 to −57 bp 5′ upstream of the translation start codon (ATG). Boxes and lines represent exons and introns, respectively (figure not drawn to scale). The locations of the primers for identification of the mutants are indicated by arrows. LB and RB, left and right borders of T-DNA insertion, respectively; LBa1, left border primer for T-DNA; LP2 and RP2, left and right genomic primers for the CPK4 gene, respectively; and T-DNA1 and T-DNA2, first and second copies of the inserted T-DNAs, respectively, noting that the two copies were inserted in an inverted manner. nt, nucleotides.

(B) T-DNA insertion sites in cpk11-1 (Col ecotype; SALK_023086, ABRC) and cpk11-2 (Col ecotype; SALK_054495, ABRC). Tandem T-DNA of two copies was inserted into the genome for the cpk11-1 mutant in an inverted fashion at the same locus, which generates a 34-bp deletion from −120 to −87 bp 5′ upstream of the translation start codon (ATG). A single copy of T-DNA was inserted for the cpk11-2 mutant, generating a 39-bp deletion from 320 to 358 bp downstream of the translation start codon (ATG). LP1 and LP3, two left genomic primers for the CPK11 gene; RBa1, right border primer for T-DNA; RP1, right genomic primer for CPK11 gene. Other abbreviations are the same as in (A).

(C) RT-PCR analysis of CPK4 (indicated by CPK4) and CPK11 (CPK11) expression in wild-type Col and homozygous mutants cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 and double mutants cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2. Actin2/8 primers served as control.

(D) Immunoblotting analysis with anti-CPK11C serum, which recognizes both CPK11 and CPK4, in the total proteins (20 μg for each line) extracted from leaves in wild-type Col and the CPK4-overexpressing line 12 (4OE12) and CPK11-overexpressing line 2 (11OE2). Relative band intensities, normalized relative to the intensity of Col, are indicated by numbers in boxes below the bands. Tubulin was used as a control.

(E) Real-time PCR and immunoblotting analysis of CPK4 and CPK11 during early stages before and after germination. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-CPK11C serum in the total proteins extracted from the leaves of the seedlings grown in MS medium from 1 to 10 d after stratification in homozygous mutants cpk4-1 (possessing CPK11) and cpk11-2 (possessing CPK4). Relative band intensities, normalized relative to the intensity with the seedling 3 d after stratification, are indicated by numbers in boxes below the bands. Tubulin was used as a control. For the real-time PCR analysis for each gene, the assays were repeated three times with the independent biological experiments. The value obtained from the seedlings 3 d after stratification was taken as 100%, and all the other values were normalized relative to this value. Each value for real-time PCR is the mean ± se of three independent biological determinations.

To confirm that cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 are transcript-null mutants, RT-PCR analysis was performed with RNA isolated from wild-type and mutant plants. The results showed that the three mutants did not yield their corresponding RT-PCR products under the growth conditions where wild-type plants produced normally CPK4 and CPK11 mRNA (Figure 1C). However, CPK4 transcription was not affected in the cpk11-1 and cpk11-2 mutants; likewise, CPK11 transcription was not affected in the cpk4-1 mutant (Figure 1C).

CPK4 and CPK11 share high identity (94%) in their amino acid sequences even in the most variable N or C terminus (see Supplemental Figure 3 online), and both proteins localize to the cytoplasm and nucleus (Dammann et al., 2003; Milla et al., 2006a; see Supplemental Figure 4 online). It is difficult to generate antiserum specific to distinguish the two proteins one from another because of their high amino acid sequence identity. We produced two antisera against the most variable C-terminal fragments of CPK4 (CPK4C) and CPK11 (CPK11C), respectively (see Methods and Supplemental Figure 3 online), both of which recognize both CPK4 and CPK11. Using either anti-CPK4C or anti-CPK11C serum, we detected immunosignals in all the T-DNA insertion mutants, and the signals in the cpk4-1 mutant are CPK11, whereas those in the cpk11-1 and cpk11-2 mutants are CPK4 (Figure 1E; see Supplemental Figure 5A online). This is consistent with the above-mentioned RT-PCR assays (Figure 1C). The cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutants, obtained by crossing, were shown to have neither mRNA of the two genes in their total mRNA (Figure 1C) nor immunosignal of the two proteins in their total proteins (see Supplemental Figure 5A online), revealing that both genes are disrupted from the double mutants, and indicating that the two antisera are specific to CPK4 and CPK11. The disruption of either kinase gene did not affect ABA biosynthesis when plants were grown under nonstress conditions or under drought (see Supplemental Figure 6 online) or salt stress. It should be noted that the two allelic T-DNA insertion lines cpk11-1 and cpk11-2, as well as two double mutants cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2, show similar phenotypes in response to ABA or stress treatments. Thus, in this report, we show the results of cpk11-2 as a representative of two mutants cpk11-1 and cpk11-2 and the results of cpk4-1 cpk11-2 as a representative of the two double mutants in some cases.

We also created CPK4- and CPK11-overexpressing lines under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. Ten lines were obtained, and their phenotypes related to ABA and stress tolerance were similar. We show only CPK4 overexpression line 12 (4OE12) and CPK11 overexpression line 2 (11OE2) as examples in this report. Immunoblotting assays showed that the levels of CPK4 or CPK11 protein significantly increased in these overexpression lines (Figure 1D).

Available data at the Genevestigator website (http://www.genevestigator.ethz.ch) show that both CPK4 and CPK11 genes are expressed in different plant organs. Consistent with this observation, we showed that the mRNA and protein of both kinases are present in all the organs tested (see Supplemental Figure 5A online). Gene expression detected in the germinating seeds showed that expression levels increased rapidly during the first 3 d after stratification, kept relatively stable thereafter for >10 d, and increased once again from ∼20 d after germination (Figure 1E; see Supplemental Figure 5B online).

ABA Stimulates Both CPK4 and CPK11 Kinases

Ca2+ binding proteins, such as CDPKs, migrate in gels at different rates in the Ca2+-bound versus Ca2+-free state (Roberts and Harmon, 1992). To investigate this phenomenon, we added Ca2+ or EGTA to the protein sample just before electrophoresis and then the in gel phosphorylation was analyzed in the presence of Ca2+. Assays of in-gel autophosphorylation of both kinases showed a clear mobility shift when the kinase migrated in the presence of Ca2+ (see Supplemental Figure 7A online). The in-gel histone-phosphorylating activity of both kinases was shown to be dependent on the presence of Ca2+ (see Supplemental Figure 7B online). We also analyzed the effects of the CaM antagonists N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalene sulfonamide (W7) and trifluoperazine and the inhibitor of Ser/Thr protein kinases K252a on CPK4 and CPK11 kinases. The calcium-dependent in-gel histone-phosphorylating activity of both kinases could be inhibited by W7, trifluoperazine, and K252a (see Supplemental Figure 7B online). By contrast, CaM and N-(6-aminohexyl)-1-naphthalene sulfonamide (W5; an inactive analog of W7) had no apparent effect on phosphorylating activity of the two kinases (see Supplemental Figure 7B online). These results indicate that CPK4 and CPK11 possess enzymatic properties of a typical CDPK.

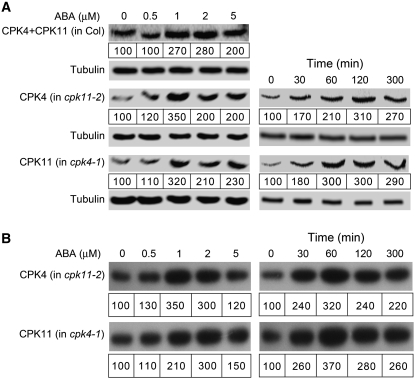

We further tested whether the two CDPKs are stimulated by ABA and found that the mRNA levels of CPK4 and CPK11 were not significantly altered by ABA treatments. However, ABA treatments significantly increased the protein levels of both CPK4 and CPK11 and correspondingly enhanced their histone-phosphorylating activities (Figures 2A and 2B). The ABA-stimulating effects were dependent on the ABA dose used, in which ABA was most effective at ∼1 μM concentration, and higher concentrations of ABA showed reduced effects (Figures 2A and 2B). This might be expected because the endogenous levels of ABA due to the exogenously applied ABA at ∼1 μM may mimic the elevated ABA levels during stressful conditions (Finkelstein and Rock, 2002), but a higher level over the physiological concentrations may be harmful to optimization of the response. The ABA-stimulating effects were also shown to be transient, with a maximum stimulation at 60 to 120 min after ABA treatments (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

ABA Stimulates both CPK4 and CPK11.

ABA treatment enhances both protein amounts (A) and enzymatic activities (B) of CPK4 and CPK11, which depends on ABA dose and displays a time course. In the ABA-dose assays, germinating seeds were transferred, 48 h after stratification, to MS medium containing (±)ABA (0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 μM), and 10-d-old seedlings were used for preparation of total proteins. The CPK4 and CPK11 were immunodetected with the anti-CPK4C serum in the total proteins from Col plants (left panel in [A], indicated by CPK4+CPK11 in Col), the CPK4 with the anti-CPK4C serum in the total proteins from the cpk11-2 mutant (left panel in [A], indicated by CPK4 in cpk11-2), and the CPK11 with the anti-CPK11C serum in the total proteins from the cpk4-1 mutant (left panel in [A], indicated by CPK11 in cpk4-1). A 20-μg portion of the total proteins was used in each line for this immunoblotting. The in-gel histone-phosphorylating activity was assayed in the pure CPK4 protein obtained by immunoprecipitation with the anti-CPK4C serum from the total proteins of the cpk11-2 mutant (left panel in [B], indicated by CPK4 in cpk11-1) and in the pure CPK11 with the anti-CPK11C serum from the total proteins of the cpk4-1 mutant (left panel in [B], indicated by CPK11 in cpk4-1). A 50-μg portion of the total protein was used in each line for the immunoprecipitation. In the time-course assays, the 3-week-old seedlings of the cpk11-2 and cpk4-1 mutants were sprayed with 50 μM (±)ABA solution, and the leaves were harvested for preparing total proteins at the indicated time after the treatment (0, 30, 60, 120, and 300 min). Immunoblotting was performed as described above for CPK4 in the total protein of the cpk11-2 mutant (right panel in [A], indicated by CPK4 in cpk11-2) and for CPK11 in the total protein of the cpk4-1 mutant (right panel in [A], indicated by CPK11 in cpk4-1). The in-gel histone-phosphorylating activity was assayed as described above in the immunoprecipitated CPK4 protein from the cpk11-2 mutant (right panel in [B], indicated by CPK4 in cpk11-2) and in the immunoprecipitated CPK11 from the cpk4-1 mutant (right panel in [B], indicated by CPK11 in cpk4-1). The assays described in the left panels of (A) and (B) were performed with the same total protein, and those in the right panels with another batch of the same total protein. Tubulin was used as a loading control. In the case of the immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting for tubulin was performed with the total protein sample prior to the immunoprecipitation. Relative band intensities, normalized relative to the corresponding intensity with 0 μM ABA or at 0 min time point, are indicated by numbers in boxes below the bands. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Disruption of CPK4 and CPK11 Reduces ABA and Salt Responsiveness in Seed Germination

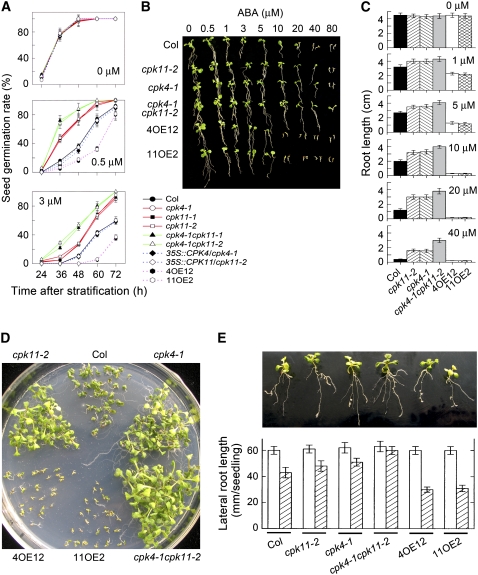

The seed of all the T-DNA insertion mutants and transgenic overexpression lines of CPK4 and CPK11 germinated normally as the wild-type seed did in the ABA-free medium (0 μM ABA; Figure 3A). However, in the media supplemented with 0.5 or 3 μM ABA, the germination rates of the T-DNA insertion mutant seed were significantly higher than those of the wild-type seed (Figure 3A). On the contrary, germination of the CPK4 and CPK11 overexpression seed was significantly more inhibited by ABA than that of the wild-type seeds (Figure 3A). The double mutants cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 resulted in significantly more intense ABA-insensitive phenotypes in ABA-induced inhibition of seed germination (Figure 3A). Similar to the responses to ABA, in the media containing different concentrations of NaCl ranging from 50 to 200 mM, the cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 mutant seeds germinated significantly faster than those of wild-type seeds with more apparent phenotypes in cpk4-1 seed but weaker phenotypes in cpk11-2 (Figure 4A) and cpk11-1. The cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutants had significantly stronger NaCl-insensitive phenotypes in NaCl-induced inhibition of seed germination than the cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 single mutants (Figure 4A). However, CPK4 and CPK11 overexpression did not significantly alter the NaCl-related phenotypes in seed germination (Figure 4A).

Figure 3.

Loss-of-Function Mutation in the CPK4 or CPK11 Gene Results in ABA-Insensitive Phenotypes, and Overexpression of the Two CDPK Genes Leads to ABA-Hypersensitive Phenotypes in ABA-Induced Inhibition of Seed Germination and Seedling Growth.

(A) Seed germination. The germination rates were recorded in MS medium supplemented with 0 μM (top panel), 0.5 μM (middle panel), or 3 μM (bottom panel) (±)ABA during a period from 24 to 72 h after stratification for wild-type Col, cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 mutants, cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutants, mutant complementation lines 35S:CPK4/cpk4-1 and 35S:CPK11/cpk11-2, and two lines overexpressing CPK4 (4OE12) or CPK11 (11OE2). Each value is the mean ± se of three biological determinations.

(B) Seedling growth 10 d after transfer from ABA-free MS medium to MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of (±)ABA for the plants as mentioned in (A). Seedlings were transferred from ABA-free medium to ABA-containing medium 48 h after stratification.

(C) Primary root growth for the same lines as mentioned in (B) in medium containing 0, 1, 5, 10, 20, or 40 μM ABA. Each value is the mean ± se of at least 50 seedlings.

(D) Postgermination growth in MS medium containing 0.8 μM (±)ABA 16 d after stratification for the plants as mentioned in (B). Seeds were planted in the ABA-containing medium, and the postgermination growth was directly investigated 16 d after stratification without transferring the seedlings.

(E) Lateral root growth in MS medium containing 1 μM (±)ABA 10 d after transfer from the ABA-free medium for the plants as mentioned in (B). Seedlings were transferred from ABA-free medium to ABA-containing medium 4 d after stratification. Top panel, status of lateral root growth. Bottom panel, statistics of lateral root growth. White columns indicate ABA-free treatment and hatched columns ABA treatment. Each value in the bottom panel is the mean ± se of at least 50 seedlings.

Figure 4.

Loss-of-Function Mutation in CPK4 or CPK11 Results in NaCl-Insensitive Phenotypes in NaCl-Induced Inhibition of Seed Germination and Decreases Tolerance of Seedlings to Salt Stress.

(A) Seed germination. Germination rates were recorded at 48, 60, and 72 h in MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of NaCl from 0 to 200 mM for wild-type Col, cpk4-1, and cpk11-2 mutants, the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant, and two lines overexpressing CPK4 (4OE12) or CPK11 (11OE2). Each value is the mean ± se of three biological determinations.

(B) to (D) Tolerance of seedlings to salt stress. The status of seedling growth was recorded 7 d after transfer of the 4-d-old seedlings from medium containing 170 (B) or 200 (C) mM NaCl. A map is presented in (D) for the distribution of wild-type Col, cpk4-1, and cpk11-2 mutants, the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant, and two lines overexpressing CPK4 (4OE12) or CPK11 (11OE2) in (B) and (C). The entire experiment was replicated three times with similar results.

The transgenic expression of CPK4 cDNA in the cpk4-1 mutant and CPK11 cDNA in the cpk11-1 and cpk11-2 mutants under the control of CaMV 35S prompter rescued the ABA- and salt-insensitive phenotypes in their seed (Figure 3A), showing that the phenotypes of cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 are indeed caused by defects in the respective CPK4 or CPK11 genes.

Disruption of CPK4 and CPK11 Reduces, but Overexpression of the Genes Enhances, ABA Sensitivity in Seedling Growth

There were no significant differences found in seedling growth in ABA-free media among the different genotypes (Figures 3B and 3C; 0 μM ABA). To assess the effects of CPK4 and CPK11 on the response of seedling growth to ABA, we used two approaches. One was that germinating seed was transferred 48 h after stratification from the ABA-free Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium to ABA-containing MS medium to investigate the response of growth to ABA (Figures 3B and 3C) and another was that seed was directly planted in ABA-containing MS medium to investigate the response of seedling growth to ABA after germination (Figure 3D). The results obtained with these two approaches were similar. The seedlings of all the T-DNA insertion mutants grew significantly better than those of wild-type Col in the ABA-containing medium, while the growth of the CPK4 and CPK11 overexpression seedlings was significantly more reduced by ABA treatment than that of the wild-type seedlings (Figures 3B to 3D). In the assays with the 48 h transferred seedlings to ABA-containing medium, the effects of ABA on seedling growth were more apparent when the applied ABA concentrations were higher than 5 μM, and the growth of the transgenic overexpression seedlings was completely inhibited in the media containing >10 μM ABA, while the seedling of wild-type Col and T-DNA insertion mutants still grew to some extent (Figures 3B and 3C). It should be noted that the phenotypes in ABA-responsive seedling growth were easily observed if the seedlings were transferred to ABA-containing medium <48 h after stratification, but the phenotypes were less apparent when the transfer took place >48 h after stratification. We have also observed the same phenomenon in the ABA receptor ABAR-regulated seedling growth (Shen et al., 2006), which may be associated with mechanisms such as the postgermination developmental arrest checkpoint mediated by temporal expression of ABI5 (Lopez-Molina et al., 2001). Double disruption of two CDPK genes, CPK4 and CPK11, in the cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 mutants resulted in significantly more intense ABA-insensitive phenotypes in ABA-induced arrest of seedling growth (Figures 3B to 3D). It is noteworthy, however, that the phenotypes associated with the postgermination growth are relatively weak, especially at the ABA concentrations lower than 10 μM (Figures 3B and 3C).

We also tested the effects of CPK4 and CPK11 on lateral root growth in relation to ABA. The results showed that, in the ABA-containing medium, the total length of lateral roots of the cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 mutants tended to increase, and that of the double mutants cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 increased significantly, relative to that of wild-type plants (Figure 3E). By contrast, overexpression of CPK4 or CPK11 significantly reduced the total length of lateral roots in the presence of ABA compared with wild-type Col (Figure 3E).

Disruption of CPK4 and CPK11 Leads to Salt Hypersensitivity in Seedling Growth

We further investigated the response of seedling growth to NaCl by transferring 4-d-old seedlings from the NaCl-free medium to NaCl-containing medium. There was no significant difference observed in growth status among the seedlings of various genotypes in the media containing up to 150 mM NaCl. However, NaCl at 170 mM was associated with chlorosis of the seedlings of cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 mutants, as well as cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutants, and at 200 mM NaCl, all the seedlings of the cpk4-1 mutant and cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutants were completely chlorotic (Figures 4B and 4C). The seedlings of the cpk11-1 and cpk11-2 mutants were shown to be less damaged by NaCl at above 170 mM concentrations compared with those of the cpk4-1 mutant and the two double mutants (Figures 4B and 4C).

The CPK4 and CPK11 overexpression did not significantly alter the NaCl-related phenotypes in seedling growth (Figures 4B and 4C). The transgenic complementation lines of the cpk4-1, cpk11-1, or cpk11-2 mutants rescued the NaCl-related phenotypes.

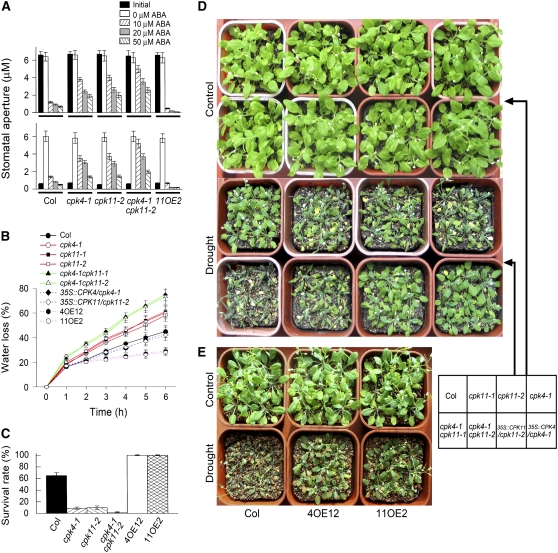

Disruption of CPK4 and CPK11 Reduces, but Overexpression of the Genes Enhances, ABA Sensitivity in Stomata and Capacity to Conserve Water

Loss-of-function mutations in CPK4 or CPK11 caused ABA-insensitive phenotypes, but overexpression of the CPK4 or CPK11 gene led to ABA-hypersensitive phenotypes, namely, ABA-induced promotion of stomatal closure (Figure 5A, top panel) and inhibition of stomatal opening (Figure 5A, bottom panel). The detached leaves of the loss-of-function mutants cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 lost more water under dehydration conditions, while CPK4- and CPK11-overexpressing plants lost less water than the detached leaves of the wild-type plants (Figure 5B). This may be due to the alteration in ABA sensitivity of stomatal closure of these genotypes (Figure 5A). Furthermore, we observed differences in the capacity to conserve water at the whole-plant level among these genotypes: when drought stress was imposed on plants, cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 mutants showed lower capacity to conserve their water (Figures 5C and 5D), but the CPK4 and CPK11 overexpression lines presented higher (Figures 5C and 5E) capacity to conserve their water than wild-type plants. In the well-watered conditions, however, no differences were observed in growth status among these genotypes (Figures 5D and 5E).

Figure 5.

Loss-of-Function Mutation in CPK4 or CPK11 Gene Decreases, but Overexpression of the Two CDPK Genes Enhances, Stomata Responsiveness to ABA and the Ability to Preserve Water in Leaves.

(A) ABA-induced stomatal closure (top panel) and inhibition of stomatal opening (bottom panel) for wild-type Col, cpk4-1, and cpk11-2 mutants, the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant, and a line overexpressing CPK11 (11OE2). Values are the means ± se from three independent experiments; n = 60 apertures per experiment.

(B) Water loss rates during a 6-h period from the detached leaves of wild-type Col, cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 mutants, cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutants, mutant complementation lines 35S:CPK4/cpk4-1 and 35S:CPK11/cpk11-1, and two lines overexpressing CPK4 (4OE12) or CPK11 (11OE2). Values are the means ± se of five individual plants per genotype. The entire experiment was replicated five times with similar results.

(C) Survival rate for wild-type and different mutant lines as mentioned in (B). Drought was imposed on the 3-week-old plants by withholding water until the lethal effect was observed on the knockout mutant plants, then the plants were rewatered and survival rate was recorded 1 week later. Values are the means ± se from three independent experiments; n = 50 plants per line for each experiment.

(D) and (E) Whole-plant status in the water loss assays. For assaying water loss from whole plants of the different lines as mentioned in (B), intact plants were well watered (control) or drought stressed by withholding water (drought) for 15 d (D) or for 18 d for assaying water loss of the two lines overexpressing CPK4 (4OE12) or CPK11 (11OE2) in comparison with wild-type Col (E). The entire experiment was replicated three times with similar results.

Double mutants cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 showed stronger ABA-insensitive phenotypes in ABA-induced promotion of stomatal closure (Figure 5A, top panel) and inhibition of stomatal opening (Figure 5A, bottom panel), and lost more water from both their detached leaves (Figure 5B) and whole plants (Figures 5C and 5D), in comparison with the single mutants cpk4-1, cpk11-1, or cpk11-2.

The transgenic complementation lines of the cpk4-1, cpk11-1, or cpk11-2 mutants showed rescued ABA-insensitive stomatal phenotypes and regained a level of water loss rates from detached leaves (Figure 5B) and an ability of preserving their water at the whole-plant level under water deficit (Figure 5D) comparable to wild-type plants, which shows that the phenotypes of cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 indeed result from disruption of CPK4 or CPK11.

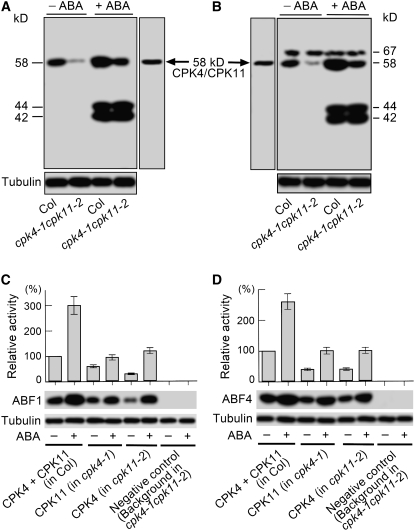

CPK4 and CPK11 Kinases Phosphorylate ABA-Responsive Transcription Factors ABF1 and ABF4 in Vitro

The ABA-responsive transcription factors ABF1, ABF2 (AREB1), ABF3, and ABF4 (AREB2) (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000) were previously reported to be phosphorylated by upstream protein kinases to mediate ABA signaling (Uno et al., 2000; Furihata et al., 2006; Fujii et al., 2007). To analyze if the ABFs are also involved in CPK4- and CPK11-mediated ABA signaling, we mapped protein kinases that could phosphorylate two ABA-responsive transcription factors, ABF1 and ABF4, through ABF1 or ABF4 in-gel phosphorylation by total proteins from wild-type Col or the double mutant cpk4-1 cpk11-2. ABF1 was phosphorylated apparently by the kinase(s) of sole molecular mass of 58 kD, but ABF4 by kinases of two molecular masses of 58 and 67 kD in the absence of exogenous ABA treatment (Figures 6A and 6B). However, in the presence of exogenous ABA, both ABF1- and ABF4-phosphorylating kinases displayed two additional bands of 42 and 44 kD (Figures 6A and 6B). These 42- and 44-kD phosphorylating activities are consistent with previous reports of SnRK activities on the ABFs (Uno et al., 2000; Furihata et al., 2006; Fujii et al., 2007). Immunoblotting assays indicated that CPK4 and CPK11 migrate at 58 kD (Figures 6A and 6B), showing that the 58-kD phosphorylating activities may be due to CPK4 and CPK11. Both the ABF1- and ABF4-phosphorylating activities of the 58-kD kinases, apparently stimulated by ABA, was clearly reduced but did not disappear in the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant (Figures 6A and 6B), indicating that a large portion of 58-kD kinases are CPK4 and CPK11, but other kinases with the same molecular mass exist to phosphorylate ABF1 and ABF4. Further experiments showed that ABF1 and ABF4 were phosphorylated in vitro by the immunoprecipitated natural proteins of both CPK4 and CPK11, and this phosphorylation was significantly stimulated by ABA treatment (Figures 6C and 6D). The ABF1- and ABF4-phosphorylating activities of CPK4 and CPK11 were completely abolished by double mutation in CPK4 and CPK11 (Figures 6C and 6D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that CPK4 and CPK11, having ABA-inducible kinase activity (Figures 2 and 6), are likely to play an important role in phosphorylating and activating ABF1, ABF4, and possibly other ABFs. It is noteworthy, however, that these two transcription factors can be phosphorylated by multiple kinases, and other 58-kD kinases are also involved in this phosphorylation event (Figures 6A and 6B).

Figure 6.

Two Protein Kinases, CPK4 and CPK11, Phosphorylate both ABF1 and ABF4.

The 3-week-old seedlings of the different genotypes were sprayed with 0 or 50 μM (±)ABA solution and were sampled 1 h after the spraying. The quantity of the total proteins, prepared from leaves and used in each lane of the following assays, was 50 μg. Tubulin was used as a protein loading control.

(A) and (B) Mapping of protein kinases phosphorylating ABF1 (A) and ABF4 (B). The recombinant ABF1 or ABF4 (0.5 mg/mL) was embedded in the separating polyacrylamide SDS gel. Total proteins from wide-type Col and the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant were separated on the gel and assayed to in-gel phosphorylate the two substrates. At the same time after electrophoresis, gels harboring the total proteins from the ABA-free-treated wild-type plants (other gels than those for phosphorylation) were used to detect immunosignals with anti-CPK4C serum to provide a reference for the position of the CPK4/CPK11 proteins in the lanes of phosphorylation (58 kD CPK4/CPK11). −ABA and +ABA indicate the treatments with 0 or 50 μM (±)ABA, respectively. The assays were repeated three times with the same results.

(C) and (D) Phosphorylation of ABF1 (C) or ABF4 (D) by CPK4 and CPK11. The mixed proteins of two kinases (CPK4 + CPK11 in Col) were obtained by immunoprecipitation with anti-CPK4C serum from the total proteins of wild-type Col, and the pure CPK11 (CPK11 in cpk4-1) and CPK4 (CPK4 in cpk11-2) were immunoprecipitated with the anti-CPK11C serum from the total proteins of cpk4-1 mutant and with anti-CPK4C serum from the total proteins of cpk11-2 mutant, respectively. The total proteins from the double mutant cpk4-1 cpk11-2 were also immunoprecipitated with anti-CPK4C serum for obtaining background in cpk4-1 cpk11-2 as a negative control to show the absence of activity other than CPK4/11 in these assays. The ABF1 and ABF4 were in-gel phosphorylated by the immunoprecipitated proteins as described in (A) and (B). Top panels (columns) represent the relative band intensities of the phosphorylated ABF1 or ABF4 shown in middle panels, normalized relative to the corresponding intensity of the wild-type Col with 0 μM (±)ABA treatment (100%). Values are the means ± se from three biological independent experiments. Immunoblotting for tubulin (bottom panels) was performed with the total proteins prior to the immunoprecipitation. The − and + indicate the treatments with 0 and 50 μM (±)ABA, respectively.

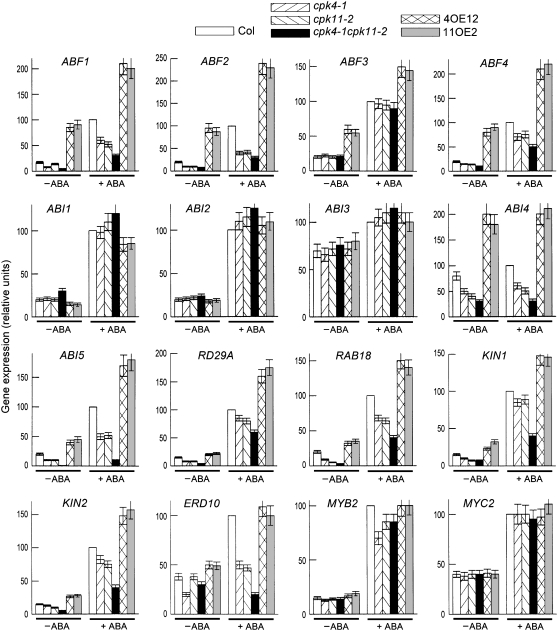

Disruption or Overexpression of CPK4 and CPK11 Alters the Expression of Some ABA-Responsive Genes

We tested the expression of the following ABA-inducible genes in the T-DNA insertion mutants and transgenic overexpression lines: ABFs (ABF1, ABF2/AREB1, ABF3, and ABF4/AREB2; Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000), ABI1 (Leung et al., 1994; Meyer et al., 1994; Gosti et al., 1999), ABI2 (Leung et al., 1997), ABI3 (Giraudat et al., 1992), ABI4 (Finkelstein et al., 1998), ABI5 (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000), RD29A (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 1994), RAB18 (Lang and Palva, 1992), KIN1 and KIN2 (Kurkela and Borg-Franck, 1992), ERD10 (Kiyosue et al., 1994), and MYB2 and MYC2 (Abe et al., 2003). As reported previously, the expression of all these ABA-responsive genes was strongly stimulated by ABA except for ABI4 (Figure 7). Disruption of CPK4 or CPK11 downregulated expression of ABF1, ABF2, ABF4, ABI4, ABI5, RD29A, RAB18, KIN1, KIN2, and ERD10, and double disruption of the two CDPK genes had stronger inhibiting effects on expression of these ABA-responsive genes, which was true both in the absence and presence of the ABA treatments (Figure 7), except for ERD10. ERD10 expression, assayed in the absence of the ABA treatments, was not significantly reduced in the cpk11-2 mutant (and cpk11-1; data not shown), in the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant (Figure 7), or in the cpk4-1 cpk11-1 double mutant (data not shown). Overexpression of CPK4 or CPK11 amplified the ABA-induced stimulating effects on these genes except for ERD10 (Figure 7). However, disruption or overexpression of CPK4 or CPK11 did not affect the expression of ABI1, ABI2, ABI3, MYB2, and MYC2, except for the cpk4-1 mutant, for which the ABA-stimulated expression level of MYB2 was downregulated, and the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant, for which the expression level of ABI1 was significantly increased in the absence of ABA treatment (Figure 7). Overexpression of CPK4 and CPK11 significantly enhanced the expression level of ABF3, but loss-of-function mutations in the CDPK genes did not show any effects (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Expression of ABA-Responsive Genes in the CPK4 and CPK11 Loss-of-Function Mutants and Overexpressing Lines.

Expression of ABA-responsive genes was assayed by real-time PCR in the leaves of wild-type Col, cpk4-1, and cpk11-2 mutants, the cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutant, and two lines overexpressing CPK4 (4OE12) or CPK11 (11OE2). −ABA, ABA-free treatment; +ABA, 50 μM (±)ABA treatment. The expression levels are presented as relative units with the levels of ABA-treated Col leaves being taken as 100%. Each value is the mean ± se of three independent biological determinations.

DISCUSSION

CPK4 and CPK11 Are Two Positive Regulators in CDPK/Ca2+-Mediated ABA Signaling

This experiment showed that two closely related CDPKs in Arabidopsis, CPK4 and CPK11, are ABA inducible and positively regulate ABA signal transduction pleiotropically in seed germination, seedling growth, and stomatal movement (Figures 2 to 5), although the ABA-related phenotypes in seedling growth are relatively weak (Figure 3). Additionally, as regulators of ABA signaling, CPK4 and CPK11 are required for plants to respond to salt stress (Figure 4), an environmental stress to which plant responses are most closely associated with the functions of ABA (Zhu, 2002; Shinozaki et al., 2003). Current evidence suggests that redundancies in CDPK genes create major obstacles to the identification of biological function through genetic approaches (Harmon et al., 2000, 2001; Hrabak et al., 2003; Choi et al., 2005; Mori et al., 2006), and only in regulation of stomatal aperture have the ABA-responsive phenotypes been detected by loss-of-function mutation in CPK3 and CPK6 (Mori et al., 2006). Our experiments showed relatively strong, pleiotropic, ABA-, and salt-responsive phenotypes that resulted from disruption or overexpression of CPK4 or CPK11 genes (Figures 3 to 5), revealing that the two CDPKs are important regulators in CDPK/Ca2+-mediated ABA signaling pathways. The CPK4 and CPK11 kinases are structurally highly similar (see Supplemental Figure 3 online) and have the similar expression profile (Figure 1; see Supplemental Figure 5 online), and both localize in cytoplasm and nucleus (see Supplemental Figure 7 online) and phosphorylate the same transcription factors ABF1 and ABF4 (Figure 6), suggesting that the two kinases may function redundantly in the same pathway. However, it is noteworthy that the double mutations in the two kinase genes resulted in stronger consequences in ABA- and some salt-responsive phenotypes than the single mutations (Figures 3 to 5). This synergistic effect in the phenotypes of the double mutants in response to ABA or salt treatments suggests that these kinases may be involved in different pathways. This further suggests that these kinases may have additional targets to ABF1 and ABF4, and these still unknown targets may be different for CPK4 and CPK11. Nevertheless, the identification of these two CDPKs as important regulators in ABA signaling pathways provides unequivocal genetic evidence for the involvement of CDPK/Ca2+ in ABA signal transduction at the whole-plant level in seed germination, seedling growth, stomatal movement, and plant response to salt-stress.

It is known that ABA regulates plant adaptation to water deficit and salt stress mainly through its functions in regulating water balance and osmotic stress/cellular dehydration tolerance. Whereas the role in water balance is mainly through guard cell regulation, the latter role is related to the induction of genes that encode dehydration tolerance proteins in nearly all cells (Zhu, 2002; Shinozaki et al., 2003). The two CDPKs CPK4 and CPK11 mediate ABA signaling to regulate stomatal aperture (Figure 5), which is likely to be mainly responsible for their function in conserving water under water-deficit conditions (Figure 5). In addition, the two kinases regulate a number of stress tolerance–related genes (Figure 7), suggesting that they may also function at the level of cellular dehydration tolerance.

ABA accumulation is a well-known consequence of salt stress, which results in inhibition of seed germination and is required for tolerance of seedling growth to salt (Zhu, 2002; Shinozaki et al., 2003). The CPK4- and CPK11-dependent salt tolerance of seedling growth (Figure 4) reveals the indispensability of the two CDPK genes for plant tolerance to salt stress, which may be ascribed to the functions of the two kinases to regulate ABA signaling. The same phenomenon was also observed in ABA signaling mutants, such as abi1 (Achard et al., 2006). It is noteworthy, however, that the CPK4 kinase plays a more important role than CPK11 in plant response to salt stress, as shown by stronger salt-responsive phenotypes in the cpk4-1 mutant (Figure 4). Furthermore, overexpression of CPK4 and CPK11 did not significantly alter plant response to salt stress (Figure 4). These phenotypes differ from those related to ABA where both kinases appear to have comparable effects on ABA responsiveness (Figures 3 and 5), and the overexpression of the two kinase genes enhanced plant capacity to conserve water (Figure 5). This divergence between the ABA and salt responsiveness suggests the possible additional involvement of the two kinases in pathways that may diverge at some point between the response to salt and to ABA.

How Do CPK4 and CPK11 Work in Mediating ABA Signal Transduction?

The CPK4 and CPK11 kinases both localize in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Dammann et al., 2003; Milla et al., 2006a; see Supplemental Figure 2 online). This double localization in cells appears to facilitate their functions in both early and delayed responses of cells to ABA (Zhu, 2002). For example, cytoplasm-localized CPK4 and CPK11 would more easily mediate a quick response by sensing Ca2+ and phosphorylating downstream messengers already in place, such as guard cell regulation, while the nuclear-CPK4 and CPK11 would be able to more easily phosphorylate nuclear-localized regulators, such as transcription factors that mediate gene expression.

What are the downstream targets of the CPK4 and CPK11 kinases to relay ABA signaling? Several ABA/stress signaling regulators, including ABA/stress-responsive transcription factors, have been shown to be modulated at the posttranslational level by changing their phosphorylation states (Li et al., 1998, 2000, 2002; Guo et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2002; Mustilli et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2002, 2006; Zhu, 2002; Shinozaki et al., 2003; Choi et al., 2005; Song et al., 2005; Milla et al., 2006a; Furihata et al., 2006; Fujii et al., 2007). Among ABA-responsive transcription factors, ABF transcription factors, including four members of the basic Leu zipper protein family, are well defined (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000; Kang et al., 2002; Fujita et al., 2005; Furihata et al., 2006; Fujii et al., 2007). We found that two ABA-responsive transcription factors, ABF1 (Choi et al., 2000) and ABF4 (AREB2) (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000), were phosphorylated in vitro by both CPK4 and CPK11 (Figure 6), but an ABA-responsive APETALA2 domain transcription factor, ABI4 (Finkelstein et al., 1998), was not (data not shown), suggesting that the two ABFs may be downstream targets of both kinases. Additionally, we showed that ABF1 and ABF4 were also phosphorylated by other, multiple, kinases besides CPK4 and CPK11 (Figure 6). These findings suggest that multiple kinases may have common substrates in ABA signaling pathways. Consistent with this observation, a recent report showed that ABF1 was also the phosphorylation target of two SnRKs, SnRK2.2 and SnRK2.3, which positively regulate ABA signaling (Fujii et al., 2007). ABF4, as well as other ABFs, ABF2 and ABF3, were previously shown to play important roles in ABA-mediated drought tolerance (Kang et al., 2002; Fujita et al., 2005). Taken together, the CPK4 and CPK11 kinases may regulate ABA signaling at least partly through the functions of their potential targets ABF1 and ABF4.

With respect to guard cell regulation, it is noteworthy that stomatal aperture may be regulated by a complex cooperation of, among other regulators, numerous protein kinases, including CPK3, CPK6 (Mori et al., 2006), and other kinases, such as SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE (SnRK) 2.6 (OST1) (Mustilli et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2002, 2006). CPK4 and CPK11 belong to the same subgroup of CDPKs as CPK6 (Hrabak et al., 2003), suggesting that these three CDPKs may possibly function in close cooperation in regulating stomatal aperture. SnRK2.6 interacts with ABI1 to regulate stomatal closure (Yoshida et al., 2006), while CPK4 and CPK11 may regulate stomatal aperture through phosphorylating ABF1 or ABF4. ABF transcription factors bind the ABA-responsive G-box motif (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000), of which the core ACGT consensus sequence is found in the promoter regions of many ABA-regulated genes, including all the 16 genes tested in this study (Figure 7) and thus may regulate expression of the CPK4 and CPK11 downstream target genes to induce ABA-related physiological responses, including stomatal regulation. Finally, it is noteworthy that CPK11 was also previously reported to interacts with At Di19, a zinc-finger protein, and to phosphorylate it in vitro (Milla et al., 2006a), and At Di19-related genes were stimulated by drought and salt stresses (Milla et al., 2006b). This suggests that CPK11, possibly in addition to CPK4, might be involved in ABA signaling or regulation of plant tolerance to stresses through a complex signaling network.

METHODS

Screening of Loss-of-Function Mutants

T-DNA insertion lines in the Arabidopsis thaliana CPK4 gene (Arabidopsis genomic locus tag: At4g09570) and CPK11 gene (At1g35670) in the Col ecotype were obtained from the Salk Institute (http://signal.salk.edu/) through the ABRC. Screening for the knockout mutants was performed following the recommended procedures. Briefly, for the T-DNA insertion in the CPK11 gene, the mutant lines were genotyped by amplifying the genomic DNA with the left genomic primer 1 (LP1) or left genomic primer 3 (LP3) and right genomic primer 1 (RP1). For the T-DNA insertion in the CPK4 gene, the mutant lines were genotyped with the left genomic PCR primer 2 (LP2) and right genomic primer 2 (RP2). These genomic primers were used together with a T-DNA left border primer (LBa1) and a right border primer (RBa1) to constitute specific primer pairs for genotyping the T-DNA insertion lines (Figures 1A and 1B). The sequences for these primers are presented in Supplemental Table 1 online. The T-DNA insertion in the mutants was identified by PCR and DNA gel blot analysis, and the exact position was determined by sequencing. We identified a homozygous T-DNA insertion allele, SALK_081860, in the 5′ UTR of the CPK4 gene, designated cpk4-1, and two homozygous T-DNA insertion alleles, SALK_023086 in the 5′ UTR and SALK_054495 in the 1st exon of the CPK11 gene, designated cpk11-1 and cpk11-2, respectively. For the cpk4-1 mutant, the PCR products could be generated with the primer pair LBa1-RP2 and LP2-LBa1 (Figure 1A; see Supplemental Figure 1 online) but not with the primer pair LP2-RBa1, indicating that tandem T-DNAs were inserted into the genome in an inverted fashion at the same locus, which was supported by DNA gel blot analysis that detected a two-copy T-DNA insertion (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). A sequencing assay showed that the T-DNA insertion generates a DNA fragment deletion in the T-DNA insertion site (see Results). For the cpk11-1 mutant, the PCR products could be generated with the primer pair LBa1-RP1 and LP3-LBa1 (Figure 1B; see Supplemental Figure 1 online) but were not found with the primer pair LP3-RBa1, indicating that, like the cpk4-1 mutant, tandem T-DNA insertion was present for the cpk11-1 mutant in an inverted fashion at the same locus, which also was supported by DNA gel blot analysis that detected a two-copy T-DNA insertion (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). Also, the T-DNA insertion generates a DNA fragment deletion in the T-DNA insertion site (see Results). For the cpk11-2 mutant, analysis of PCR, sequencing, and DNA gel blots all showed that a single copy of T-DNA was inserted into the genome (Figure 1B; see Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 online), and the T-DNA insertion also results in a DNA fragment deletion in the T-DNA insertion site (see Results). The cpk4-1 cpk11-1 and cpk4-1 cpk11-2 double mutants were constructed by crossing, and their genotypes were confirmed by PCR-based genotyping.

Mutant Complementation and Generation of Transgenic Plants

To create transgenic plant lines overexpressing the CPK4 or CPK11 gene or expressing these two genes in the knockout mutants, the open reading frame (ORF) for the CPK4 gene was isolated by PCR using the forward primer 5′-GCTCTAGAATGGAGAAACCAAACCCTAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CGGGATCC TTACTTTGGTGAATCATCAGA-3′, and the ORF for the CPK11 gene was isolated using the forward primer 5′-GCTCTAGAATGGAGACGAAGCCAAACCCTAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CGGGATCCTCAGTCATCAGATTTTTCACCA-3′. The ORF (1506 bp) of CPK4 and the ORF (1488 bp) of CPK11 were inserted into the pCAMBIA-1300-221 vector (http://www.cambia.org/daisy/cambia/materials/vectors/585.html) by XbaI and BamHI sites under the control of a constitutive CaMV 35S promoter. These constructs were all verified by sequencing and introduced into the GV3101 strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. The constructions were transformed, by floral infiltration as described previously (Clough and Bent, 1998), into plants of wild-type Col for generating the CPK4- and CPK11-overexpressing lines or into cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 mutant plants for assays of complementation. Transgenic plants were selected by hygromycin resistance and confirmed by PCR. The homozygous T3 seeds of the transgenic plants were used for further analysis.

Growth Conditions

Plants were grown in a growth chamber at 20 to 21°C on MS medium at ∼80 μmol photons m−2 s−1 or in compost soil at ∼120 μmol photons m−2 s−1 over a 16-h photoperiod at 22°C.

Phenotype Analysis

Phenotype analysis was performed essentially as previously described (Shen et al., 2006). For germination assay, ∼100 seeds each from the wild type (Col) and mutants or transgenic mutants were planted in triplicate on MS medium (Sigma-Aldrich; full-strength MS). The medium contained 3% sucrose and 0.8% agar, pH 5.7, and was supplemented with or without different concentrations of (±)ABA or NaCl. The seeds were incubated at 4°C for 3 d before being placed at 22°C under light conditions, and germination (emergence of radicals) was scored at the indicated times.

For the seedling growth experiment, seeds were germinated after stratification on common MS medium and 48 h later transferred to MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of ABA in the vertical position. Seedling growth was investigated 10 d after the transfer, and the length of primary roots was measured using a ruler. Seedling growth was also assessed by directly planting the seeds in ABA-containing MS medium to investigate the response of seedling growth to ABA after germination.

Lateral root growth assays were performed according to the protocol of Xiong et al. (2006) with some modifications. Four-day-old seedlings were individually transferred with a pair of forceps to the treatment medium consisting of the basal salts along with 4% sucrose solidified with 1.2% agar (Sigma-Aldrich). The basal salts included 1.0 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 6.0 mM KNO3, and 7.0 mM NH4NO3. Micronutrients were added at full strength (1× that used in the MS medium), and the pH was adjusted to 5.7 with KOH, and 1.0 μM ABA was added to the medium after autoclaving. After growing for 10 d on the treatment medium, seedlings were photographed with a digital camera. The length of lateral roots was measured using a ruler. The total length of lateral roots of each individual plant was calculated, and the means for each line were used as an index to measure lateral root growth.

For seedling growth in salt, seeds of wild-type, cpk4-1, cpk11-2, cpk4-1 cpk11-2, and transgenic plants were surface-sterilized, stratified at 4°C for 3 d to obtain uniform germination, and sown on common MS media without salt. Seedlings were allowed to grow for 4 d with the plates in a vertical orientation at 22°C under light conditions. The seedlings were then transferred to MS medium (full-strength MS, 3% sucrose, pH 5.7) containing 1.2% agar and different salt concentrations (0, 100, 150, 170, or 200 mM NaCl) in the vertical position using forceps. The status of seedling growth was recorded 7 d after the transfer.

For drought treatment, plants were grown on soil until they were 3 weeks old, and then drought was imposed by withdrawing irrigation for one-half of the plants until the lethal effects were observed on most of these plants, whereas the other half were grown under a standard irrigation regime as a control.

For water loss assay, rosette leaves were detached from their roots, placed on filter paper, and left on the lab bench. The loss in fresh weight was monitored at the indicated times.

For stomatal aperture assays, leaves were floated in the buffer containing 50 mM KCl and 10 mM Mes-Tris, pH 6.15, under a halogen cold-light source (Colo-Parmer) at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 for 2 h followed by addition of different concentrations of (±)ABA. Apertures were recorded on epidermal strips after 2 h of further incubation to estimate ABA-induced closure. To study inhibition of opening, leaves were floated on the same buffer in the dark for 2 h before they were transferred to the cold light for 2 h in the presence of ABA, and then apertures were determined.

Production of Anti-CPK4 and Anti-CPK11 Sera

A fragment of CPK4 cDNA corresponding to C-terminal 116 amino acids (from 386 to 501) was isolated using forward primer 5′-CCGGAATTCATGGCTTGCACAGAGTTTGGTCT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ACGCGTCGACTTACTTTGGTGAATCATCAGA-3′, and a fragment of CPK11 cDNA corresponding to C-terminal 109 amino acids (from 387 to 495) was isolated using forward primer 5′-CCGGAATTCATGGCTTGCACAGAGTTTGGTCT-3′ and reverse primer 5′- ACGCGTCGACTCAGTCATCAGATTTTTCACCA-3′. They were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) as glutathione S-transferase (GST) CPK4C and GST-CPK11C fusion proteins. The affinity-purified fusion protein was used for standard immunization protocols in rabbit. The antisera were affinity purified. Each antiserum, anti-CPK4 or anti-CPK11 serum, was shown to recognize both CPK4 and CPK11 because the C terminus of the two CDPKs shares high sequence identity. However, the two antisera do not cross-react with any other proteins. Therefore, in most cases, we used one of the two antisera to detect the CPK4 or CPK11.

Extraction of Proteins and Protein Determination

Total protein extracts were obtained from Arabidopsis plants by grinding whole seedlings or leaf tissue first in liquid nitrogen and then on ice for 3 h in 1 volume of the extraction buffer. The extraction buffer consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg mL−1 antipain, 5 μg mL−1 aprotinin, and 5 μg mL−1 leupeptin. Lysates were cleared of debris by centrifugation at 12,000g for 30 min at 4°C.

Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (1976) with BSA as a standard. Fifty micrograms of total proteins were used for each extract for protein concentration determination.

Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

SDS-PAGE was performed according to the method of Laemmli (1970). The protein samples (20 μg) were boiled for 2 min before being analyzed on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Immunoblotting was performed essentially as described by Yu et al. (2006). After SDS-PAGE, the proteins on gels were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 μm; Amersham Pharmacia). The membranes were blocked for 2 h at room temperature with 3% (w/v) BSA and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 in a Tris-buffered saline containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl and then were incubated with gentle shaking for 2 h at room temperature in the rabbit polyclonal antibodies anti-CPK4C (1:3000) or anti-CPK11C serum (1:1000) diluted in the blocking buffer. After being washed three times for 10 min each in the Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with the alkaline phosphatase–conjugated antibody raised in goat against rabbit IgG (diluted 1:1000 in the blocking buffer) at room temperature for 1 h and then washed three times for 10 min each with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. Protein bands were visualized by incubation in the color-development solution using a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium substrate system according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein band intensity was estimated by densitometric scans using a digital imaging system and analyzed with QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad). Tubulin, immunodetected with anti-rat tubulin serum (Sigma-Aldrich), was used as a loading control.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation was performed essentially as described by Yu et al. (2006). The total proteins (50 μg) were resuspended in 0.5 mL immunoprecipitation buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg mL−1 antipain, 5 μg mL−1 aprotinin, 5 μg mL−1 leupeptin, and 0.5% Triton X-100. The mixture was incubated with either the purified anti-CPK4C or anti-CPK11C serum (∼3 μg protein) or the same amount of preimmune serum protein (as a control) at 4°C for 2 h. Then, 25 μL protein A-agarose suspension was added to the mixture, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h. Following a brief centrifugation, the immunoprecipitated proteins, after three washes with the immunoprecipitation buffer, were used for the assays of immunoblotting or kinase activity.

In-Gel Kinase and Autophosphorylation Assays

In-gel kinase activity assay of proteins was performed essentially as described by Yu et al. (2006). After SDS-PAGE as described above but with the separating polyacrylamide SDS gel that was polymerized in the presence of 0.5 mg mL−1 histone III-S as a substrate for kinases, the gels were washed twice with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 20% (v/v) 2-propanol for 1 h per wash and then with buffer A composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mM EDTA for 1 h at room temperature. Proteins in the gels were denatured by incubating the gels in buffer A containing 6 M guanidine hydrochloride for two incubations of 1 h each at room temperature. Proteins were then renatured using buffer A containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 for six incubations of 3 h each at 4°C. After preincubation at room temperature for 30 min with buffer B composed of 40 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.45 mM EGTA (1 mM in the Ca2+-free medium), and 2 mM DTT in the absence or presence of 0.55 mM CaCl2, the gels were incubated with buffer B containing 50 μM ATP and 10 μCi/mL [r32-P]-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia) for 1 h at room temperature. The gels were then washed extensively with 5% trichloroacetic acid and 1% sodium pyrophosphate until radioactivity in the used wash solution was barely detectable. The gels were then stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R 250 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). After destaining, the gels were air dried between two sheets of cellophane, and the histone III-S in gel phosphorylated by CDPK was detected by autoradiography after exposition of the dried gels to Kodak X-Omat AR film for 5 to 7 d at −20°C. Films were scanned using a digital imaging system, and radioactivity was quantified with QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad).

For Ca2+-dependent electrophoretic mobility shift of the kinases in the in-gel autophosphorylating activity assays, Ca2+ or EGTA to a final concentration of 2 mM was added to the immunoprecipitated proteins dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The in-gel autophosphorylation assay of CDPK was performed as described above, except that the separating gel was polymerized in the absence of substrate.

Preparation of ABF1 and ABF4 Proteins and Phosphorylation Assay

To prepare recombinant ABF1 and ABF4, their coding regions were prepared by PCR. For ABF1, the primers used were 5′-CGGGATCCGATGGGTACTCACATTGATATC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-CCCAAGCTTTTACCACGGACCGGTAAGGGTTC-3′ (reverse primer). For ABF4, the primers were 5′-GGAATTCTATGGGAACTCACATCAATTTCAAC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCACCATGGTCCGGTTAATGTCCT-3′ (reverse primer). The PCR product was digested with BamHI and HindIII (ABF1) or EcoRI and SalI (ABF4) and subcloned into pET-48 b(+) vector (Novagen) for the production of His fusion protein using E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen). The cell lysate was applied to the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column (Qiagen) and processed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified proteins were dialyzed with 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, for 16 h at 4°C and stored at −80°C in working aliquots. Phosphorylation of His-ABF1 and His-ABF4 was performed as described above, except when separating the immunoprecipitated proteins on an SDS-PAGE gel that contained 0.5 mg/mL His-tagged ABF1 or ABF4 as potential substrates of the protein kinases.

RT-PCR and Real-Time PCR Analysis

RT-PCR analysis was performed to analyze the expression of CPK4 and CPK11 genes. Total RNA was isolated from leaves of 3-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings with the RNasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) supplemented with an on-column DNA digestion (Qiagen RNase-Free DNase set) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and then the RNA sample was reverse transcribed with the Superscript II RT kit (Invitrogen) in 25 μL volume at 42°C for 1 h. PCR was conducted at linearity phase of the exponential reaction for each gene. The gene-specific primer pairs were as follows: for CPK4, forward primer 5′-GAGAAACCAAACCCTAGAAGACC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CAGGTGCAACATAATACGGAC-3′; and for CPK11, forward primer 5′-CCCTAGACGTCCTTCAAACACA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CTCTGGTGCAACATAGTACGG-3′. Actin (At5g09810) expression level was used as a quantitative control.

To assay the expression levels of CPK4 and CPK11 genes after ABA treatment, quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed with the RNA samples isolated from 3-week-old seedlings harvested at the indicated times after 50 μM ABA treatments (mixed isomers; Sigma-Aldrich). Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription were performed as described above for RT-PCR. PCR amplification was performed with primers specific for CPK4 or CPK11 genes: for CPK4, forward 5′-TCTGTGACACTCCTCTTGATGAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTCATCTACAAAAGTGGAAACG-3′; and for CPK11, forward 5′-CGAAGAAGAACCAACAAAAAACC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCATACATCTTCGTAATCCTCG-3′. Amplification of ACTIN2/8 (forward primer 5′-GGTAACATTGTGCTCAGTGGTGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AACGACCTTAATCTTCATGCTGC-3′) genes was used as an internal control (Charrier et al., 2002). The suitability of the oligonucleotide sequences in term of efficiency of annealing was evaluated in advance using the Primer 5.0 program. The cDNA was amplified using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa) using a DNA Engine Opticon 2 thermal cycler (MJ Research) in 10 μL volume with the following program: one cycle of 95°C, 10 s; and 40 cycles of 94°C, 5s; 58.5°C, 20s; 72°C, 20s. The amplification of the target genes was monitored every cycle by SYBR-green fluorescence. The Ct (threshold cycle), defined as the PCR cycle at which a statistically significant increase of reporter fluorescence was first detected, was used as a measure for the starting copy numbers of the target gene. Relative quantitation of the target gene expression level was performed using the comparative Ct method. Three technical replicates were performed for each experiment.

To assay the expression of ABA-responsive genes, real-time PCR analysis was performed with the RNA samples isolated from 3-week-old seedlings harvested 5 h after the treatments with or without 50 μM ABA, except for ABI3, of which the expression was assayed with the seedlings grown in the ABA-free MS medium for 4 d and then transferred to the ABA-free (a control) or 50 μM ABA-containing medium for 5 d. Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription were performed as described above. PCR amplification was performed with oligonucleotides specific for various ABA-responsive genes: RD29A (At5g52310) forward 5′-ATCACTTGGCTCCACTGTTGTTC-3′ and reverse 5′-ACAAAACACACATAAACATCCAAAGT-3′; MYB2 (At2g47190) forward 5′-TGCTCGTTGGAACCACATCG-3′ and reverse 5′-ACCACCTATTGCCCCAAAGAGA-3′; MYC2 (At1g32640) forward 5′-TCATACGACGGTTGCCAGAA-3′ and reverse 5′-AGCAACGTTTACAAGCTTTGATTG-3′; RAB18 (At5g66400) forward 5′-CAGCAGCAGTATGACGAGTA-3′ and reverse 5′-CAGTTCCAAAGCCTTCAGTC-3′; KIN1 (At5g15960) forward 5′-ACCAACAAGAATGCCTTCCA-3′ and reverse 5′-CCGCATCCGATACACTCTTT-3′; KIN2 (At5g15970) forward 5′-ACCAACAAGAATGCCTTCCA-3′ and reverse 5′-ACTGCCGCATCCGATATACT-3′; ERD10 (At1g20450) forward 5′-TCTCTGAACCAGAGTCGTTT-3′ and reverse 5′-CTTCTTCTCACCGTCTTCAC-3′; ABI1 (At4g26080) forward 5-AGAGTGTGCCTTTGTATGGTTTTA-3′ and reverse 5′-CATCCTCTCTCTACAATAGTTCGCT-3′; ABI2 (At5g57050) forward 5′-GATGGAAGATTCTGTCTCAACGATT-3′ and reverse 5′-GTTTCTCCTTCACTATCTCCTCCG-3′; ABI3 (At3g24650) forward 5′-TCCATTAGACAGCAGTCAAGGTTT-3′ and reverse 5′-GGTGTCAAAGAACTCGTTGCTATC-3′; ABI4 (At2g40220) forward 5′-GGGCAGGAACAAGGAGGAAGTG-3′ and reverse 5′-ACGGCGGTGGATGAGTTATTGAT-3′; ABI5 (At2g36270) forward 5′-CAATAAGAGAGGGATAGCGAACGAG-3′ and reverse 5′-CGTCCATTGCTGTCTCCTCCA-3′; ABF1 (At1g49720) forward 5′-TCAACAACTTAGGCGGCGATAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCAACCGAAGATGTAGTAGTCA-3′; ABF2 (At1g45249) forward 5′-TTGGGGAATGAGCCACCAGGAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GACCCAAAATCTTTCCCTACAC-3′; ABF3 (At4g34000) forward 5′-CTTTGTTGATGGTGTGAGTGAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGTTTCCACTATTACCATTGC-3′; ABF4 (At3g19290) forward 5′-AACAACTTAGGAGGTGGTGGTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CTTCAGGAGTTCATCCATGTTC-3′. Amplification of ACTIN2/8 genes was used as an internal control, and real-time quantitative PCR experimental procedures were performed as described above. Three technical replicates were performed for each experiment.

For all the above quantitative real-time PCR analysis, the assays were repeated three times along with three independent repetitions of the biological experiments, and the means of the three biological experiments were calculated for estimating gene expression.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database under the following accession numbers: At4g09570 (CPK4), At1g35670 (CPK11), At1g49720 (ABF1), and At3g19290 (ABF4).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Identification of T-DNA Insertion for cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 Mutations in the Arabidopsis Genome by PCR Analysis.

Supplemental Figure 2. DNA Gel Blot Analysis for the T-DNA Insertion in cpk4-1, cpk11-1, and cpk11-2 Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 3. Alignment of Deduced Amino Acid Sequences of CPK4 and CPK11.

Supplemental Figure 4. Subcellular Localization of CPK4 and CPK11.

Supplemental Figure 5. Expression of CPK4 and CPK11 in Different Tissues and during Different Growth Periods.

Supplemental Figure 6. ABA Concentrations in the Different Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 7. Enzymatic Characterization of CPK4 and CPK11.

Supplemental Table 1. Analysis of T-DNA Insertion into the Arabidopsis Genome for Identification of the cpk4 and cpk11 Knockout Mutants.

Supplemental Methods. DNA Gel Blot Analysis, Subcellular Localization of CPK4 and CPK11, and ABA Measurement.

Supplemental References.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 30330420, 30421002, 30471193, and 30671444) and by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant 2003CB114302).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Da-Peng Zhang (zhangdp@sohu.net).

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Abe, H., Urao, T., Ito, T., Seki, M., Shinozaki, K., and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2003). Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcription activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 15 63–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard, P., Cheng, H., Grauve, L.D., Decat, J., Schoutteten, H., Moritz, T., Straeten, V.D., Peng, J., and Harberd, N.P. (2006). Integration of plant responses to environmentally activated phytohormonal signals. Science 311 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, M., McMichael, R.M.J., Huber, J.L., Kaiser, W.M., and Huber, S.C. (1995). Partial purification and characterization of a calcium-dependent protein kinase and an inhibitor protein required for inactivation of spinach leaf nitrate reductase. Plant Physiol. 108 1083–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, M., Shiraishi, N., Campbell, W.H., Yoo, B.C., Harmon, A.C., and Huber, S.C. (1996). Identification of a Ser-543 as the major regulatory phosphorylation site in spinach leaf nitrate reductase. Plant Cell 8 505–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier, B., Champion, A., Henry, Y., and Kreis, M. (2002). Expression profiling of the whole Arabidopsis shaggy-like kinase multigene family by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Plant Physiol. 130 577–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.H., Willmann, M.R., Chen, H.C., and Sheen, J. (2002). Calcium signaling through protein kinases. The Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase gene family. Plant Physiol. 129 469–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H., Hong, J., Ha, J., Kang, J., and Kim, S.Y. (2000). ABFs, a family of ABA-responsive element binding factors. J. Biol. Chem. 275 1723–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H., Park, H.J., Park, J.H., Kim, S., Im, M.Y., Seo, H.H., Kim, Y.W., Hwang, I., and Kim, S.Y. (2005). Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK32 interacts with ABF4, a transcriptional regulator of abscisic acid-responsive gene expression, and modulates its activity. Plant Physiol. 139 1750–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann, C., Ichida, A., Hong, B., Romanowsky, S.M., Hrabak, E.M., Harmon, A.C., Pickard, B.G., and Harper, J.F. (2003). Subcellular targeting of nine calcium-dependent protein kinase isoforms from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 132 1840–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.M., Zhao, Z.X., and Assmann, S.M. (2004). Guard cells: A dynamic signaling model. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7 537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, R.R., Gampala, S., and Rock, C. (2002). Abscisic acid signaling in seeds and seedlings. Plant Cell 14(suppl.): S15–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, R.R., and Lynch, T.J. (2000). The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell 12 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, R.R., and Rock, C. (2002). Abscisic acid biosynthesis and signaling. In The Arabidopsis Book, C.R. Somerville and E.M. Meyerowitz, eds (Rockville, MD: American Society of Plant Biologists), pp. 1–48.

- Finkelstein, R.R., Wang, M.L., Lynch, T.J., Rao, S., and Goodman, S.M. (1998). The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response locus ABI4 encodes an APETALA2 domain protein. Plant Cell 10 1043–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, H., Verslues, P.E., and Zhu, J.K. (2007). Identification of two protein kinases required for abscisic acid regulation of seed germination, root growth, and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 484–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Y., Fujita, M., Satoh, R., Maruyama, K., Parvey, M.M., Seki, M., Hiratsu, K., Ohme-Takagi, M., Shinozaki, K., and Yamagushi-Shinozaki, K. (2005). AREB1 is a transcription activator of novel ABRE-dependent ABA signaling that enhances drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 3470–3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furihata, T., Maruyama, K., Fujita, Y., Umezawa, T., Yoshida, R., Shinozaki, K., and Yamagushi-Shinozaki, K. (2006). Abscisic acid-dependent multisite phosphorylation regulates the activity of a transcription activator AREB1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 1988–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudat, J., Hauge, B.M., Valon, C., Smalle, J., Parcy, F., and Goodman, H.M. (1992). Isolation of Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell 4 1251–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]