Abstract

The spindle checkpoint delays sister chromatid separation until all chromosomes have undergone bipolar spindle attachment. Previous studies have revealed BUB3, as an essential spindle checkpoint protein and its extensive sequence similarity with Rae1 (Gle2), a highly conserved member of WD40 repeat protein family throughout their length which was first shown to be involved in mRNA export. However, the recent discovery of Rae1 as an essential mitotic checkpoint protein, based on the studies from mouse and drosophila, has renewed the interest in its function during cell division. Study of evolution of proteins involved in checkpoint might throw light on evolution of eukaryotic cell cycle regulation. Here we report the evolutionary relationships between these two WD40 repeat family proteins. Amino acid sequences of BUB3 and Rae1 homologs were retrieved from various databases and phylogenetic analysis was performed with the MEGA program. Multiple sequence alignments of these two protein homologues with the ClustalX software revealed specific amino acid signatures corresponding to the protein function and also few amino acids, which are conserved in BUB3 and Rae1 indicating some common overlapping function. Data indicated a common ancestral origin of these two important proteins and further suggest that, BUB3 mediated cell cycle checkpoint might have evolved with compartmentalization of genetic material into the nucleus in eukaryotes.

Keywords: WD40, BUB3, Rae1, molecular evolution

Background

Central task of cell division is the correct distribution of the genetic material to the daughter cells. This is achieved by assembling the chromosomes at the metaphase plate followed by simultaneous separation of the sister chromatids during successive phases of cell division. Eukaryotic cells have checkpoints, to avoid the initiation of chromatid separation, at which progression of cell cycle is delayed until all the chromosomes are attached to the spindle. The mitotic spindle cell cycle checkpoint coordinates the timing of these events and acts as input mechanism for DNA damage/stress pathways. Failure of this precise network leads to genomic instability and/or cell death. Mutations in the genes encoding essential checkpoint proteins lead to chromosome instability and promote carcinogenesis and other abnormalities [1]. Kinetochores of chromosomes that are not yet aligned at the metaphase plate and attached to microtubules activate the mitotic checkpoint, leading to inhibition of the Anaphase Promoting Complex (APC) [2]. Current models propose that checkpoint proteins associated with kinetochores act as sensors for microtubule-kinetochore attachement and kinetochore tension. In the absence of attachement or tension, they act to generate a molecular “anaphase wait” signal [3,4,5]. Activated checkpoint proteins then bind to Cdc20, thereby preventing it from activating the APC. It is thought that the invention of the checkpoint was a critical innovation at the emergence of eukaryotic cells. Our current understanding of the molecular basis for the mitotic checkpoint was founded on the discovery of genes in the budding yeast, which are essential for mitotic arrest when the spindle is damaged.

Studies on the mitotic checkpoint in yeast and other organism have resulted in the identification of the WD40-repeat containing protein family genes BUB3 and Rae1 as essential components of the checkpoint mechanism (see below for explanation). The WD40 repeat (also known as the Trp-Asp or WD40 motif) is found in a multitude of eukaryotic proteins involved in a variety of cellular processes. Where studied, repeated WD40 repeat motifs act as a site for protein-protein interaction, and proteins containing WD40 repeats are known to serve as platforms for the assembly of protein complexes or mediators of transient interplay among other proteins. BUB3 was originally discovered in a mutant of S. cerevisiae that failed to arrest in the cell cycle when treated with the microtubule-depolymerizing drug Benomyl [6]. BUB3 is part of a protein complex that interacts with the kinetochore before all chromosomes have achieved bipolar attachement to the mitotic spindle. Rae1, (also called Gle2 or mrnp41) has been thought to be, a highly conserved nuclear transport factor that is involved in the pathway for mRNA export during interphase, but whose precise role remains unclear [7,8]. However, several previous studies [9,10] suggested that Rae1 function is also required for a process other than mRNA export, which is essential for the progression through mitosis.

The mitotic checkpoint protein BUB3 shares extensive sequence homology with Rae1 [11,12] indicating functional similarity and a potential common origin. The homology is not restricted to the WD40 repeats, but extends over the entire protein length and is especially high in the segment that links WD40 repeats 3 and 4. Thus, BUB3 and Rae1 represent two branches of a common gene family. The human protein hsRae1, which has been found in the cytoplasm at the nuclear envelope and in the nucleus, is a shuttling transport factor, which interacts with the nucleoporin Nup98 through a specific domain called the GLEBS motif [13]. GLEBS motifs are also present in the mitotic checkpoint proteins Bub1 and BubR1, where they serve as binding sites for BUB3 [14]. BUB3 exclusively binds to GLEBS sequences of mitotic checkpoint proteins. However, Rae1 binds not only to Nup98 but also to Bub1 [14]. Based on these findings it was proposed that Rae1 like BUB3, acts as a mitotic checkpoint protein [1]. Recently, a Rae1 protein has been characterized as a G1 phase regulator of the cell cycle from drosophila by using reverse genetics approach [15]. Taken together, these results indicate that Gle2/Rae1 could be involved either in mRNA export and/or in cell cycle regulation.

The previous studies on sequence comparison and the phylogenetic analysis with limited BUB3 and Rae1 homologues of E. nidulans, drosophila, caenorhabditis, humans and mice suggested that BUB3 and Rae1 proteins across all species are about 30% identical to each other and in all the species studied contained four WD40 motifs [11]. However, phylogenetic analysis suggested that BUB3 and Rae1 homologues represent two distinguishable sets of proteins forming two distinct branches in the phylogenetic tree. This study carried out to gain evolutionary insight of BUB3 and Rae1 proteins which are involved in the cell cycle regulation, by using the sequence information available through the public domain from plant, fungal, mammalian, bacterial Archaeal genomes and other taxa expecting to reveal the ancient means of checkpoint and the evolution of BUB3 and Rae1. Attempts were made to identify conserved amino acids in both BUB3 and Rae1 proteins possibly leading to the functional overlap in the sequence region between the ultimate and penultimate WD40 domains.

Methodology

Sequence retrieval

The sequences of previously characterized BUB3 (P26449) and Rae1 (P41838) were downloaded from the Swiss-Prot database [16]. Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL and TrEMBL_NEW databases were searched using the Yeast cell-cycle arrest protein BUB3 and poly (A+) mRNA export protein Rae1, to identify respective homologs. To identify the ancestral WD40- repeat containing proteins individual ORGN databases at NCBI were searched using the BLAST algorithm [17]. To identify the number of WD40 repeats and additional domains individual sequences were searched against the InterPro [18] and SMART [19] database.

Phylogenetic analysis

Partially and completely known amino acid sequences have been used for phylogenetic analysis. To check the sequence conservation between BUB3 and Rae1 we used the T-COFFEE sequence alignment tool [20]. The sequence pool in FASTA format was processed by the multiple alignment program ClustalX (version 1.81) [21], using the Gonnet series as protein weight matrix and parameters set to 10 gap opening, 0.2 for gap extension, and divergent sequences delay at 30%. Sequence conservation was visualized and manually edited using the BioEdit programme (version 5.0.9.) [22] and BOXSHADE 3.21 programme [23]. Exclusion of positions with gap had no significant effect on the topology of the trees. Indels were searched for sequence signatures. Protein distance matrices were calculated using the Gonnet matrix and evolutionary trees were constructed by neighbor-joining method [24]. Support for the nodes was estimated by the bootstrap procedure, using 1000 re-samplings of the data. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) 3.6 programme [25] was employed in all steps of tree construction. The Tree figures were generated and final printouts was obtained using the Tree View programme (version 1.60) [26].

Results and discussion

Sequence data retrieval

We had chosen the Swiss-Prot database because it is a curated protein sequence database, which strives to provide a high level of annotations, a minimal redundancy and high level of integration compared to other databases. TrEMBL is a computer-annotated supplement of Swiss-Prot that contains all the translations of EMBL nucleotide sequence entries not yet integrated in Swiss-Prot. Individual databases of worm, fly, arabidopsis and yeast were also searched for the additional BUB3 and Rae1 homologs. Due to the occurrence of un-annotated proteins and large number of the WD40 repeat containing proteins, we limited ourselves to the Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL and TrEMBL_NEW. The database search for the yeast BUB3 homologs resulted in 46 sequences with a cut off E-value of 10-4 including several mitotic checkpoint and Rae1 proteins as well as few hypothetical and putative proteins from various sources (Table 1 under supplementary material). Similar search with yeast Rae1 retrieved 101 homologues with E-value ranging from e-121 to 4e-10. Both BUB3 and Rae1 homologues were manually searched for the repetitions and found all BUB3 homologues with in an E-value range of 7e-27 in the BLAST output with Rae1 as query sequence. However, we could retrieve three additional sequences of the mitotic checkpoint homologs from Cryptosporidium parvum (CAD98277), hypothetical Rae1-like protein of Arabidopsis thaliana (Q38942) and PAXP protein from Leishmania major (Q25349). All the sequences retrieved below this E-value mostly Beta transducine, Serine/Threonine protein kinase, transcriptional repressors and other functions resulted due to the common occurence of WD40 repeats. We eliminated them in the final phylogenetic analysis after confirming their grouping with the other functionally related WD40 repeat proteins (data not shown). All the fragments retrieved from TrEMBL_NEW, except Q8MPF0 from Taenia solium as it was not changing the tree topology and representing different taxa, were eliminated from the final phylogenetic analysis. The similarity searches for the WD40 repeat containing proteins in the archaea bacteria resulted in the retrieval of a single protein containing WD40-repeats from Methanosarcina acetivorans str. C2A. (NP_617428). Earlier, presence of WD40 repeat had been suggested in prokaryotic organisms like cyanobacteria with significant E-value [27]. However, to the best of our knowledge this sequence was never used in the phylogenetic analysis for any of the members of WD40 repeat family proteins. Presence of WD40 repeats protein in Archaea and cyanobacteria facilitated the use of these sequences as out-group source, and also to predict the ancient form of spindle checkpoint, in the phylogenetic analysis.

Domain analysis and multiple sequence alignments

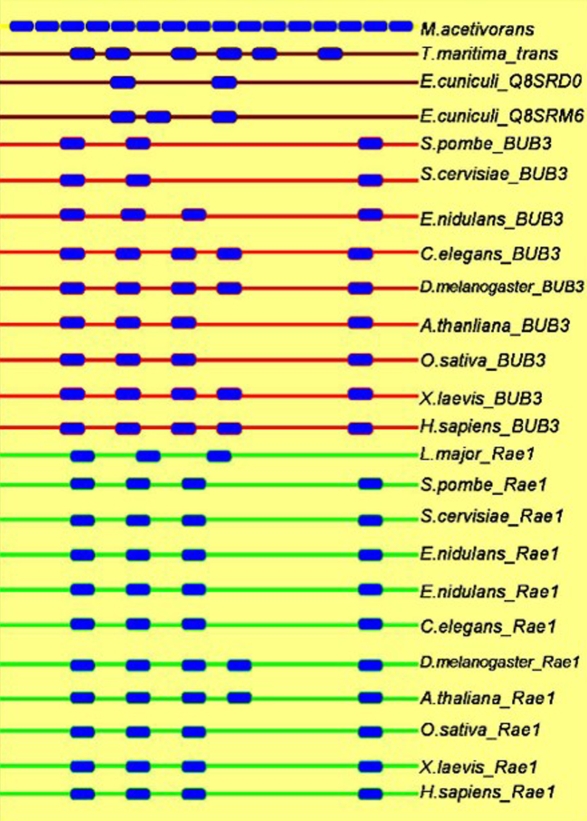

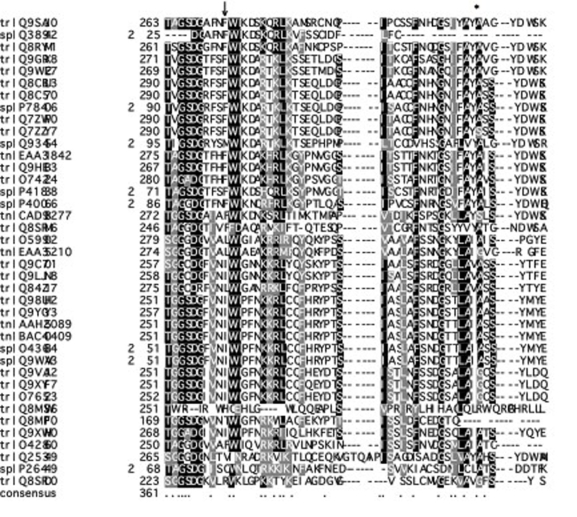

We also carried out domain analysis of BUB3 and Rae1 proteins from various organisms from fungi, yeast, plants, vertebrates, invertebrates and archaea bacteria. Figure 1 gives the representative organization and number of WD40 repeats in various proteins from different taxa. Result showed that, archaea bacteria had only a single copy of WD40 protein with sixteen WD40 domains that might be involved in different cellular functions. Later on the number of WD40 repeat domain reduced down to three/four in BUB3/Rae1 in fungi. There after the number increased to four/five in BUB3 of plants and humans. But in Rae1 the number of WD40 repeats in plants was five and in humans it was four. However, in C. elegans the BUB3 protein had five WD40 repeats and Rae1 had only four. The probable reason for decrease in the number of WD40 repeats, compared to archaea in eukaryotes could be their specialization in specific cellular processes. In the two microsporidial proteins, one protein had only two and the other was having the three WD40 domains while the protein of T. curvata seven WD40 repeat domains. It is central assumption of evolution that gene duplications provide the genetic raw material to create proteins with new functions. As these homologs evolved in higher eukaryotes, they acquired some additional domains such as C-terminal carboxidase and PPAT domains, which might have specific function. We had eliminated four such proteins from final phylogenetic analysis as they were forming a separate cluster in the cladogram assuming that these proteins, which are hypothetical and do not have any functional characterization except the homology prediction. Compilation and analysis of amino acid sequences of a particular protein from a variety of biological sources can provide us with the amino acid sequence signatures that are important for the function of that protein. Keeping this in view a closer examination of aligned amino acid sequence alignments was performed. In agreement with the earlier studies the sequence homology extended over the entire protein length with semi-conserved substitutions and was especially high in the segment that links WD40 repeats 3 and 4 (Figure 2) between the two groups of proteins. This analysis revealed specific amino acid signatures in terms of conserved amino acids at specific sites in the given groups of proteins. As shown in Figure 2 the entire Rae1 group proteins had phenylalanine (F) (marked with ↓ in Figure 2) while BUB3 proteins had mainly leucine (L) and isoleucine (I). Similarly tyrosine (Y) was identified in all Rae1 like proteins, with alanine (A) on either side. In case of BUB3 proteins, this tyrosine was replaced with either isoleucine (I), valine (V) or leucine (L) at the same position (marked with * in Figure 2). In earlier analysis, glycine (G) had been shown as conserved amino acid in all Rae1 homologs and this was not conserved in the BUB3 proteins [12]. Our analysis with the homologues from Rae1 and BUB3 also showed the same conservation for glycine in all the Rae1 proteins. Probably this glycine might have active site role in Rae1, as the change of glycine to glutamic acid in Rae1-1 mutant of S. pombe resulted in loss of function [7]. Additionally, we identified phenylalanine (an aromatic amino acid) in all the BUB3 proteins and even in E. cuniculi Rae1 (data not shown) protein. This result indicated that E. cuniculi Rae1 protein (Q8SRM6) might have role in cell division activity (see phylogenetic analysis for more supporting evidence) and further it might have evolved with more specific activity such as mitotic spindle checkpoint protein in eukaryotes.

Figure 1.

Domain analysis with different BUB3 proteins from various organisms. Filled boxes with blue color represent WD40 domains. Domains with red line represent BUB3 like proteins while Rae1 like proteins with green lines. The proteins having both the activity are in brown lines.

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment showing the function specific amino acid signatures. The entire Rae1 group proteins had phenylalanine (F) (marked with ↓) while BUB3 proteins had mainly leucine (L) and isoleucine (I). Similarly tyrosine (Y) was identified in all Rae1 like proteins (marked as *), with alanine (A) on either side. In case of BUB3 proteins, this tyrosine was replaced with isoleucine (I), valine (V) or leucine (L) at the same position.

Phylogenetic analysis

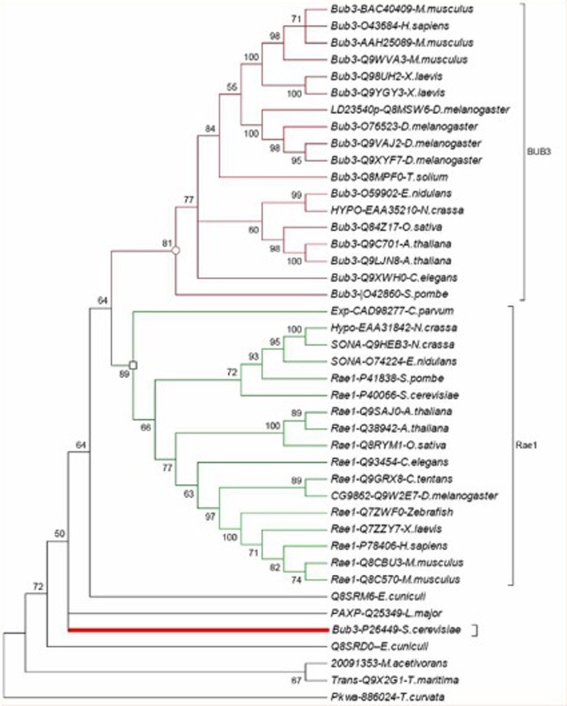

Distance based phylogenetic trees of WD40 repeat proteins involved in spindle checkpoint function were determined from the alignment using neighbor-joining algorithms. As the outgroup sampling minimizes alignment instability and maximizes taxonomic and subfamily protein diversities, we had included the sequences of proteins having WD40 repeats from Methanosarcina acetivorans str. C2A (Archaea bacteria), Beta transducin-related protein of Thermotoga maritima and PkwA protein of Thermomonospora curvata as outgroup source. Since the proteins with either Rae1 or BUB3 like functions have WD40 repeats, the out-groups also helped in finding probable ancient organism having either of specified function. In particular, determining the position of the root in this tree could help in establishment of the order of emergence of different proteins in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes.

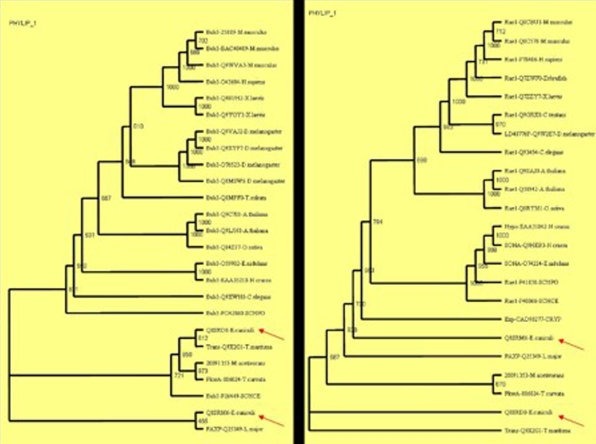

Comparative phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequences from BUB3 and Rae1 proteins, which are involved in spindle checkpoint mechanism from various taxa, like fungi, plants, vertebrates and invertebrates showed that they fall in to two distinct functional clades. Clade I contained the cell cycle arrest protein BUB3 homologs and clade II included homologs of poly (A)+ RNA export protein Rae1 (Figure 3). This result was similar to previous report with limited number of BUB3 and Rae1 homologs [11]. Consensus phylogenetic tree of BUB3 and Rae1 homologs revealed the major evolutionary lineages such as archaea, eubacteria and eukaryotes except for the E. cuniculi (see below for explanation), in the same way as do generally relied on Phylogenetic markers such as ribosomal RNA or the transcription factor EF1a and places the archaea near the T. maritima. The phylogenetic functional analysis suggested not only that functions have been conserved with in orthologous groups but also that the generation of the orthologous groups was accompanied by functional divergence.

Figure 3.

Consensus phylogenetic tree based on BUB3 and Rae1 protein sequences.

However, a closer look in to the consensus phylogenetic tree (Figure 3) revealed that BUB3 of S. cervisiae (P26449) was grouped with the homologues from archaea bacteria (gi_2009135), T. maritima (Q9X2G1), T. curvata (886024) and E. cuniculi (Q8SRDO) indicating that the BUB3 of S. cervisiae was more closely related to the prokaryotic sequences rather than the sequences from the eukaryotic lineages, while BUB3 of the S. pombe was forming a coherent group with the other eukaryotic sequences. However, Rae1 of S. cervisiae, was grouped with the S. pombe and/or other non-fungal eukaryotes. This finding was in agreement with the differences found by in a study to detect the lineage specific loss and divergence of functionally linked genes in eukaryotes, by comparing 4,344 available sequences from the fission yeast S. pombe with all eukaryotic sequences [28]. They concluded that, at least 300 genes that have been present in the common ancestor of fungi/plants and animals have been lost and another 300 or so have diverged far beyond expectation in S. cervisiae including those of the spliceosome, signalsome and the post transcriptional gene silencing systems. More recently, in an attempt to study the origin of eukaryotic cell using a set of 347 Eukaryotic Signature Proteins (ESPs), BUB3 was identified as a member of the Eukaryotic Signature Protein associated with signaling systems [29]. Another major discrepancy in the Bub3 phylogeny was seen with the C. elegans BUB3 which was placed with the fungal lineages. Unfortunately this protein is poorly characterized in terms of function and specificity making it difficult to infer attributes of this protein. (This was the only WD40 member of whole WD40 repeat family of C. elegans that was close to the BUB3).

Interestingly the phylogenetic tree of BUB3 and Rae1 homologs included several apparently pan-eukaryotic orthologs, in particular from the highly degraded genome of the microsporidium E. cuniculi and the early branching kinetoplastids L. major. In microsporidia with two Rae1 (mRNA associated protein of Rae1 family-Q8SRM6 and poly (A)+ RNA export protein-Q8SRD0) proteins, none branched together, as they would be expected to do, if they were recently diverged paralogs. Therefore it seems most likely that the progenitors of each of these orthologous sets were present in the genome of the last common ancestor of all extant eukaryotes. It is possible to have the Rae1 genes independently diverging in the same organism when only one is needed - T. curvata for example, that makes a schema for the evolution of the BUB3 from one of the two microsporidial genes is appealing. To further test this and to reveal ancient stages of checkpoint we constructed two independent trees with the BUB3 (Figure 4a) and Rae1 (Figure 4b) homologues, the three out-group sequences, two E. cuniculi (Q8SRM6 and Q8SRD0) and L. major (Q25349) proteins.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees based on the individual BUB3 (a) and Rae1 (b) protein sequences with same outgroup sequences.

As expected one of the microsporidial proteins (Q8SRD0) grouped with the BUB3 homologs in the BUB3 phylogenetic tree and the other protein (Q8SRM6) was forming an out-group cluster with the intracellular trafficking PolyA export protein (PAXP) of Leishmania major which is an ancient protozoan that diverged early in the eukaryotic evolution [30], indicating their functional similarity. This was clearer if we look at the phylogenetic tree of Rae1 homologues as these sequences were tightly clustered with the other eukaryotic sequences. However in the Rae1 phylogenetic tree the E. cuniculi (Q8SRD0) and β-transducine like protein (Q9X2G1) of T. maritima were forming orphan out-groups indicating their functional divergence and unrelated function. BUB3 probably contained sequences that were not recognizable as WD40 motifs but that fold to form propellers in the structure [11]. If we extend this hypothesis to the above results of the β-transducine like protein (Q9X2G1) of T. maritima which is forming a tight cluster with the other BUB3 homologs, we can conclude that this protein might function similarly as the BUB3.

The most interesting in the phylogeny of individual BUB3 and Rae1 homologues was unequivocally, the PkwA of prokaryotic eubacteria T. curvata was forming a tight cluster with the archaea bacteria and was closest to the root. Protein kinase AfsK from S. coelicolor exhibited sequence similarity at the N-terminal part to the PKC and RACK complex, which are involved in regulation of secondary metabolite production, organism's complex growth cycle and interaction with a subset of proteins that mediate signal relay by phosphorylation. With recent findings and the ability to form propeller like structure with the WD40 repeats, it can be concluded that PkwA might also be a precursor in spindle checkpoint pathway. We could not find any homologs from the L. major that had functions like BUB3.

Based on the observed order of evolution of Rae1 and BUB3, the Rae1 mediated checkpoint was the original form of the cell division checkpoint mechanism. The BUB3 might have evolved later with the compartmentalization of genetic material, into the nucleus in the primitive eukaryotic cell in order to coordinate the division of the cytoplasm with that of the nucleus. Previously, fission yeast Rae1 has been suggested to be involved in the import of proteins required for mitosis into the nucleus [10], indicating the possible fundamental connection between the nuclear envelope, the machinery of nuclear pores and the proteins that control the mitotic checkpoint.

Evolutionary analysis helps in improving our understanding of observed molecular characterization and making biologically useful predictions. We used the phylogenetic information to infer likely function of some of the hypothetical or uncharacterized proteins, since the function is conserved between orthologs proteins in a subfamily. For example, based on the cluster it could be speculated that the hypothetical proteins of Neurospora crassa (EAA31842), Caenorhabditis elegans (Q93454) and Drosophila melanogaster (Q9W2E7) had similar role as of Rae1 like function of mRNA export. Similarly, hypothetical proteins from Neurospora crassa (EAA35210) and Drosophila melanogaster were probably part of pathway in spindle checkpoint mechanism as these were grouped with other BUB3 proteins.

Conclusion

Significant insight the evolutionary processes of checkpoint genes was achieved by comparison of the WD40 repeat containing proteins, BUB3 and Rae1 homologues from different organisms. Functional analysis of BUB3 and Rae1 proteins showed that haplo-insufficiency of either Rae1 or BUB3 resulted in a similar phenotype involving mitotic checkpoint defects and chromosome mis-segregation. Over expression of Rae1 could correct the Rae1 haplo-insufficiency as well as BUB3 haplo-insufficiency suggesting Rae1 and BUB3 as related proteins with essential, overlapping and co-operating roles in mitotic checkpoint [1]. More recently, Rae1 was found to inhibit the APC by binding to APC-Cdh1 complex [31]. Molecular phylogenetic analysis using information of the amino acid sequences from archaea-bacteria, bacteria, fungi, plants, nematode, fly, human and mouse sequences gave strong support not only for the conserved evolution of spindle checkpoint genes but also the identical, conserved and semi conserved substitutions in the amino acid signatures between the two groups of proteins. In this light, further comparison of BUB3 and Rae1 proteins could serve to better elucidate the roles played by these proteins in the spindle checkpoint mechanism.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

D. M. R. S. Reddy acknowledges Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India, for the Senior Research Fellowship for the financial assistance.

References

- 1.Babu JR, et al. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters JM. Mol Cell. 2002;9:931. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman DB, et al. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1955. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jallepalli PV, Lengauer C. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:109. doi: 10.1038/35101065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah JV, Cleveland DW. Cell. 2000;103:997. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoyt MA, et al. Cell. 1991;66:507. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JA, et al. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zenklusen D, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4219. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4219-4232.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabri N, Visa N. RNA. 2000;6:1597. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whalen WA, et al. Yeast. 1997;13:1167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970930)13:12<1167::AID-YEA154>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Exposito MJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor SS, et al. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pritchard CE, et al. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:237. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, et al. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sitterlin D. Gene. 2004;326:107. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. http://www.expasy.org

- 17.Altschul SF, et al. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/index.html

- 19. http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de

- 20. http://www.ch.embnet.org

- 21.Thompson JD, et al. Nucl Acids Res. 1997;24:4876. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html

- 23. http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html

- 24.Saitou N, Nei M. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felsenstein J. Cladistics. 1989;5:164. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page RD. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith TF, et al. Trends in Biochem Sci. 1999;24:181. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravind L, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200346997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartman H, Fedorov A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032658599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myler PJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2902. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeganathan KB, et al. Nature. 2005;438:1036. doi: 10.1038/nature04221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.