Abstract

In Drosophila ovaries, distinct Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) pathways defend against transposons in somatic and germline cells. Germline piRNAs predominantly arise from bidirectional clusters and are amplified by the ping-pong cycle. In this study, we characterize a novel Drosophila gene, kumo and show that it encodes a conserved germline piRNA pathway component. Kumo contains five tudor domains and localizes to nuage, a unique structure present in animal germline cells, which is considered to be the processing site for germline piRNAs. Transposons targeted by the germline piRNA pathway are derepressed in kumo mutant females. Moreover, germline piRNA production is significantly reduced in mutant ovaries, thereby indicating that kumo is required to generate germline piRNAs. Kumo localizes to the nuage as well as to nucleus early female germ cells, where it is required to maintain cluster transcript levels. Our data suggest that kumo facilitates germline piRNA production by promoting piRNA cluster transcription in the nucleus and piRNA processing at the nuage.

Keywords: Drosophila ovary, germline, nuage, piRNA, tudor domain

Introduction

Diverse transposons are present in most eukaryotic genomes. These elements can flourish if they are able to colonize individual genomes and to spread within a population. To do so, these elements must target germline cells. However, transposition in the germline causes many deleterious effects, including gene disruption, transcriptional misregulation and chromosome rearrangement, which can completely disrupt fecundity. Animals have a small RNA-based defence mechanism that produces Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) to mitigate gonadal transposon activity (Malone and Hannon, 2009; Khurana and Theurkauf, 2010; Senti and Brennecke, 2010; Siomi et al, 2011). Piwi, Aubergine (Aub) and Argonaute3 (Ago3) are three Piwi family proteins in Drosophila that slice transposon transcripts in a sequence-specific manner based on the piRNAs they bind, forming the core of piRNA pathway. The piRNAs are derived from discrete genomic regions called ‘piRNA clusters’, which are densely populated by fragmented transposons that are incapable of mobilization. Most clusters contain transposons on both the plus and minus strands and are bidirectionally transcribed (Saito et al, 2006, 2009; Vagin et al, 2006; Brennecke et al, 2007; Li et al, 2009; Malone and Hannon, 2009).

Although the molecular mechanism of piRNA production remains elusive, sequencing analysis of piRNAs bound to Piwi family proteins has suggested that piRNAs may arise from two processing pathways (reviewed by Senti and Brennecke, 2010). Precursor piRNA transcripts, those arise from piRNA clusters, are randomly cleaved into 23–29 nucleotide (nt) piRNAs, an event known as primary processing. The resulting antisense piRNAs bind to Aub and subsequently carry out secondary processing during which they cleave sense transposon mRNAs into sense piRNAs. These sense piRNAs are loaded onto Ago3 and cleave antisense cluster transcripts into new antisense piRNAs. This feed-forward amplification loop, the ‘ping-pong cycle’, is conserved from lower invertebrates to mammals. While the piRNAs in somatic cells mostly arise from primary processing, those in germline cells are generated by both primary and secondary processing (Brennecke et al, 2007; Gunawardane et al, 2007; Li et al, 2009; Malone et al, 2009; Saito et al, 2009).

Aub and Ago3, the key components of the ping-pong cycle, localize to the nuage, a distinct perinuclear cytoplasmic structure that is well known in animal germline cells. Many other proteins, including Vasa (Vas), Spindle-E (SpnE), Tejas (Tej), Krimper (Krimp) and Maelstrom (Mael), localize to nuage and help to maintain nuage structure, germline piRNA production and transposon repression (Liang et al, 1994; Findley et al, 2003; Lim and Kai, 2007; Malone et al, 2009; Patil and Kai, 2010). Nuage components interact both genetically and physically. Loss of nuage-associated gene function disrupts nuage organization and piRNA production, suggesting that nuage serves as a processing site for piRNAs in the germline. Many nuage components, including Tej, Krimp and SpnE, contain tudor domains, which are motifs that bind symmetrically di-methylated arginine (sDMA) residues on Piwi family proteins (Kirino et al, 2009; Nishida et al, 2009). Many tudor domain family members facilitate germline development and gametogenesis in organisms ranging from flies to vertebrates (Siomi et al, 2010).

In this study, we describe a novel, conserved nuage component encoded by kumo. Kumo is closely related to the mouse tudor domain protein Tdrd4/RNF17, which is required for male germ cell differentiation (Pan et al, 2005). Specifically, kumo mutant females exhibit defects shared by animals lacking other germline piRNA pathway components, such as altered polarity, delayed oocyte specification and transposon depression (Chen et al, 2007; Klattenhoff et al, 2007; Lim and Kai, 2007; Patil and Kai, 2010). Deep sequencing revealed that germline but not somatic piRNA production is significantly affected in kumo mutant ovaries. Kumo localizes to perinuclear nuage and within germ cell nuclei, during early stages of the germline development. In kumo mutant ovaries, putative precursor piRNAs from dual-strand piRNA clusters are reduced, while an increased amount of HP1 associates with such clusters. These results suggest that Kumo actively opposes the spread of heterochromatin into piRNA clusters by sequestering HP1. We propose that Kumo supports piRNA production in two ways: it facilitates cluster transcription in the nucleus in early germ cells and it stimulates piRNA processing within the perinuclear nuage in the cytoplasm through out female germline development.

Results

kumo encodes a conserved tudor domain protein harbouring a RING motif and it is required for female fertility

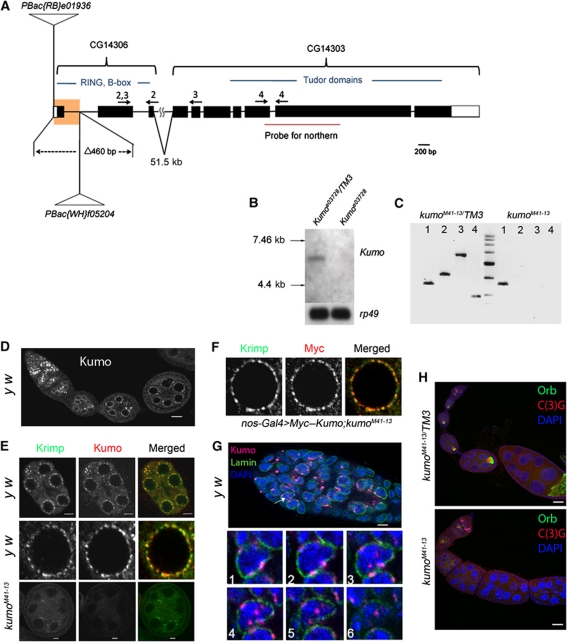

Tudor domain proteins play important roles in Drosophila germline development and transposon repression via the piRNA pathway (Siomi et al, 2010). We previously reported that CG14303, which is predicted to encode a tudor domain protein, is highly expressed in undifferentiated female Drosophila germline cells (Kai et al, 2005). Because two CG14303 cDNAs, which were obtained from the Drosophila genomics resource centre (DGRC), were truncated and possibly did not contain the 5′ moiety of the transcript, we screened a λ-ZAP ovarian cDNA library. The CG14303 cDNA isolated, also encompassed another annotated gene, CG14306, which is located ∼51.6 kb from CG14303 (Figure 1A; Flybase). Sequencing of this cDNA revealed that the region between CG14303 and CG14306 was spliced into one transcriptional unit. Northern blot analysis with the control ovarian RNA confirmed the expected transcript, which was ∼6.1 kb in size (Figure 1B). However, the transcript was undetectable in an insertion allele, CG14303e03728, harbouring a PiggyBac insertion in the second to last exon of CG14303 (Figure 1B). We further confirmed the 51.5-kb intron between CG14306 and CG14303 by RT–PCR with the ovarian RNA extracted from the control (Figure 1C, lane 2). The gene consisting of CG14303 and CG14306 is hereafter referred to as kumo, which means ‘cloud’ in Japanese. kumo appears to encode a protein of 1857 amino acids. CG14306 encodes the N-terminal region that contains one RING and two B-box domains and CG14303 encodes five tudor domains, which span the rest of the protein. kumo is an evolutionarily conserved gene; the nearest mouse homologue is Tdrd4/RNF17, which also forms cytoplasmic foci in germline cells and has been reported to be essential for the differentiation of male germ cells (Pan et al, 2005). To study the function of kumo in Drosophila, a deletion allele, kumoM41-13, was generated by the excision of a 460-bp region, containing the potential start codon, between two PiggyBac insertions, e01936 and f05204, via FLP-mediated recombination (Schlake and Bode, 1994) (Figure 1A). RT–PCR with primer sets spanning kumo (denoted in Figure 1A) detected robust expression of the kumo transcript in the heterozygous ovaries but not in kumoM41-13 mutant ovaries (Figure 1C), demonstrating that kumoM41-13 is a loss-of-function allele. This allele was used in the rest of our study, kumoM41-13 mutants exhibited female sterility, decreased egg laying and abnormal egg appendages, suggesting that kumo is essential for female germline development (Supplementary Figure S1; Supplementary Table SI).

Figure 1.

Kumo localizes to the nuage and nucleus in the germarium and is required for oocyte fate maintenance. (A) Schematic representation of the kumo locus, consisting of two previously annotated genes, CG14303 and CG14306, which are 51.6 kb apart. The region highlighted in yellow represents a deletion of 460 bases in the kumoM41-13 allele by FRT recombination, which encompasses the first exon and the following intron, including the predicted start codon. Positions of PiggyBac insertions are represented in CG14306. The arrows indicate the primer sets used for RT–PCR. (B) Northern blot analysis of the kumo transcript. A transcript of ∼6 kb was detected in the ovarian RNA extracted from the control, but it was not detected in that from kumoe03728 ovaries. (C) RT–PCR with the primer sets denoted in Figure 1A showing the absence of the kumo transcript in kumoM41-13 ovaries. Lane 1, actin control; lanes 2–4, primers against either CG14306 or CG14303 as shown in Figure 1A. (D) y w ovariole immunostained for Kumo showing the expression in germline cells. Perinuclear foci in nurse cells are discernible. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E) (Upper panel) Co-localization of Kumo (red) with a known nuage component, Krimp (green). Scale bar: 5 μm. (Middle panel) Closer view of a single nurse cell nucleus. (Lower panel) Kumo expression is undetectable in a kumoM41-13 egg chamber, and Krimp was mislocalized from the perinuclear nuage. Scale bar: 5 μm. (F) A single nurse cell nucleus showing the co-localization of Myc–Kumo (red) with Krimp (green). (G) (Upper panel) Nuclear localization of Kumo (red, indicated with arrow) in the germarium, which was co-stained for Lamin (green) and DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 10 μm. (Lower panels) Optical sections of germline cells in germarium showing the perinuclear and nuclear foci of Kumo. (H) The control heterozygous and kumoM41-13 ovarioles stained for oocyte markers Orb (green) and C(3)G (red) and DAPI (blue). Orb and C(3)G are undetectable in the egg chambers of stage two and onward in the kumoM41-13 ovary. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Kumo localizes to the nuage and to the nucleus in the germarium

We generated antibodies against Kumo to study its localization and expression pattern in the ovaries. Kumo was broadly expressed in germline cells of the germarium and in nurse cells of the egg chambers but not in somatic cells (Figure 1D and E). Kumo predominantly localized to foci in the perinuclear region in nurse cells that resembled the nuage, a unique structure present in animal germline cells (Mahowald, 1968; Eddy, 1974) (Figure 1E). Co-staining with a known nuage component, Krimp and the nuclear envelope marker, Lamin, revealed that Kumo co-localizes with Krimp on the cytoplasmic face of the nuclear membrane (Lim and Kai, 2007) (Figure 1E; Supplementary Figure S2). Myc–Kumo, expressed by a germline driver, nosGal4, also co-localized with Krimp (Figure 1F), which further confirmed that Kumo is a perinuclear nuage component. In addition to perinuclear localization in the nurse cells, Kumo also appeared as foci in the nuclei of the germ cells, mostly in regions 2a and 2b of the germarium (Figure 1G; Supplementary Figure S3 for Myc–Kumo). Both the perinuclear and nuclear signals of Kumo were undetectable in kumoM41-13 mutant ovaries, further supporting the specificity of the antibody and that kumoM41-13 is a loss-of-function allele (Figure 1E; Supplementary Figure S4).

kumoM41-13 mutant females have defects observed in mutants of other germline piRNA pathway components

We examined kumo mutant ovaries for defects that are generally exhibited by other nuage component mutants, such as failure of karyosome compaction, delay in oocyte fate determination and defects in polarity formation (Findley et al, 2003; Chen et al, 2007; Klattenhoff et al, 2007; Lim and Kai, 2007; Pane et al, 2007; Khurana and Theurkauf, 2010; Patil and Kai, 2010). The ovaries were immunostained for the oocyte marker Orb and the synaptonemal complex component C(3)G to study oocyte fate determination and karyosome compaction (Page and Hawley, 2001; Huynh and St Johnston, 2004). Loss of Orb and C(3)G staining in the egg chambers after stage two in at least 48% (n=140) of 2-day-old kumo mutant flies indicated a loss of oocytes during ovary development. The loss of oocytes after stage two became more severe with age, as ∼90% (n=109) of the mutant ovarioles showed a loss of C(3)G and Orb staining (Figure 1H; Supplementary Figure S5A). We observed germline stem cells harbouring round fusomes and differentiating cysts with branched fusomes, even after 15 days of eclosion, in kumo mutant ovaries (Supplementary Figure S6), thereby indicating that the kumo mutation does not cause defects in the maintenance or differentiation of germline stem cells (Supplementary Figure S6). We examined oocyte fate determination and karyosome compaction in young kumoM41-13 mutant ovaries that maintained oocytes. In the control, C(3)G staining was observed in a single oocyte nucleus from region 3 of the germarium and beyond and the staining became extrachromosomal in egg chambers by the stage 3 (Supplementary Figure S5B). However, in kumo mutant ovaries, ∼92% (n=79) of the ovarioles exhibited more than one pro-oocyte nucleus in stage one egg chambers by C(3)G staining, suggesting a delay in oocyte fate determination (Supplementary Figure S5B). C(3)G also remained in the nuclei of the stage 4 kumo mutant egg chambers, indicating a failure of the oocyte nucleus to compact into a karyosome. Next, we examined whether kumo mutants also exhibited defects in polarity formation by performing immunostaining with Gurken, a dorsal marker (Gonzalez-Reyes et al, 1995). Whereas Gurken was properly localized at the anterior–dorsal region in most of the control oocytes, it was mislocalized in 34.4% of kumo mutant ovarioles in 2- to 3-day-old females, indicating a mild defect in polarity formation in at least young kumo mutant ovaries. Therefore, kumo mutant ovaries exhibit the same defects, observed in other nuage component mutants, such as oocyte fate determination, karyosome compaction and defects in polarity formation, suggesting that kumo may function in the same pathway as the other nuage components.

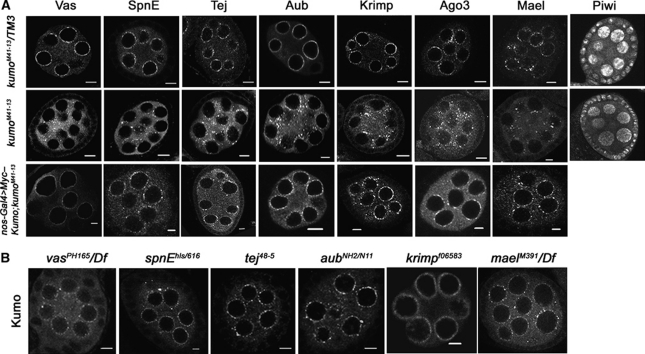

kumo is required for the localization of other nuage components to the perinuclear region

Nuage components have been shown to genetically interact with each other for their proper localization to the perinuclear nuage and these interactions are likely to follow a hierarchical order. Current genetic interaction studies suggest that vas is the most upstream component, followed by spnE, tej, aub, krimp and mael (Lim and Kai, 2007; Pane et al, 2007; Patil and Kai, 2010). To address if kumo also participates in organization of the nuage, localization of the nuage proteins was examined by immunostaining in kumo heterozygous and mutant ovaries. In the kumo mutant ovaries, all examined nuage components were mislocalized from their characteristic perinuclear position to the cytoplasm as small foci (Figure 2A). In addition, we also observed a slight reduction of Piwi in kumo mutant germline cells. In reciprocal experiments, the perinuclear localization of Kumo was not affected in ovaries of all examined nuage component mutants (Figure 2B). Myc–Kumo expression in kumo mutant germline cells restored Vas, SpnE Tej, Aub, Krimp, Ago3 and Mael localization to the perinuclear region (Figure 2A), which confirmed that Kumo is required for the localization of other piRNA pathway proteins to the perinuclear nuage. It has been shown previously that mutations in the DNA damage signalling pathway rescue the polarity defects in certain piRNA pathway mutants (Klattenhoff et al, 2007). Therefore, we investigated whether the hierarchy of nuage organization is dependent on DNA damage. Immunostaining revealed that perinuclear localization of the nuage components Aub, Krimp and Kumo were not affected in the DNA damage pathway mutants (chk2, mei41 and meiW68), which indicates that the DNA damage pathway does not play a role in nuage organization (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 2.

kumo genetically interacts with other components of the piRNA pathway. (A) The heterozygous (upper panel) and kumo mutant (middle panel) ovaries immunostained for other nuage components. All of the examined components are mislocalized from the perinuclear nuage in the kumo mutant ovaries. Piwi expression is also slightly reduced in the kumo mutant. Myc–Kumo expression (lower panel) in kumo mutant germline cells rescues the defects in the perinuclear localization of Vas, Tej, Krimp, Aub and Ago3. (B) Immunostaining for Kumo in other nuage component mutant ovaries. Perinuclear localization of Kumo in nurse cells is unaffected in all of the examined mutants. Scale bars: 5 μm.

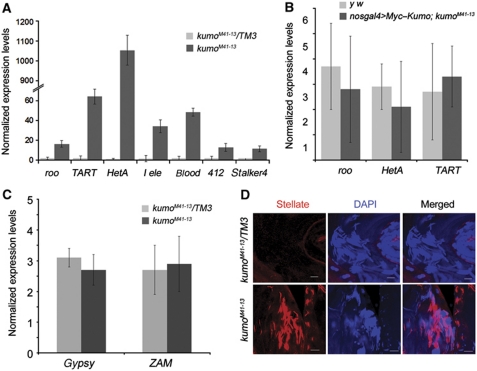

kumo is required for the repression of transposons via the germline piRNA pathway

In Drosophila, nuage has been proposed to be the processing site for germline piRNAs (Siomi et al, 2011). The localization of Kumo to nuage and its important role in nuage organization prompted us to investigate its role in transposon repression. We observed a derepression of transposons that are expressed in the germline, such as roo, I-element, HeT-A, TART, blood, 412 and stalker4, in kumo mutant ovaries (Figure 3A). Similar levels of derepression of these transposons were observed in the other piRNA pathway mutants, spnE and mael (Supplementary Figure S8). However, transposons that are predominantly expressed in the somatic cells, such as gypsy and ZAM, were not affected in the kumo mutant ovaries (Figure 3C) (Malone et al, 2009). The expression of Myc–Kumo in kumo mutant germline cells rescued the derepression of roo, HeT-A and TART to a level comparable to that of the control, which confirmed the requirement of kumo for the regulation of transposon expression (Figure 3B). Moreover, we observed robust derepression of Stellate protein expression in kumo mutant testes. Stellate is known to be regulated by the su(ste) piRNA generated by the germline piRNA pathway (Aravin et al, 2001, 2004) (Figure 3D), which further suggests that loss of kumo affects germline piRNA production in both females and males.

Figure 3.

kumo is involved in the repression of transposons. (A) Quantitative RT–PCR using ovarian RNA extracted from kumo mutant and control ovaries showing the expression levels of representative transposons expressed in the germline. Significant upregulation is seen in the kumo mutant ovaries compared with those in the heterozygous control. (B) Quantitative RT–PCR showing the relative expression levels of roo, HeT-A and TART in ovaries expressing Myc–Kumo in kumo mutant germline cells and control y w ovaries. (C) Quantitative RT–PCR showing no significant differences in the expression levels of gypsy and ZAM transposons, predominantly expressed in somatic cells, between kumoM41-13/TM3 and kumoM41-13 ovaries. The expression levels were normalized with the controls, actin5c and rp49. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of three independent sets of experiments. (D) Immunostaining for Ste (red) with DAPI (blue) showing the upregulation of Ste in kumo mutant testis. Scale bar: 20 μm.

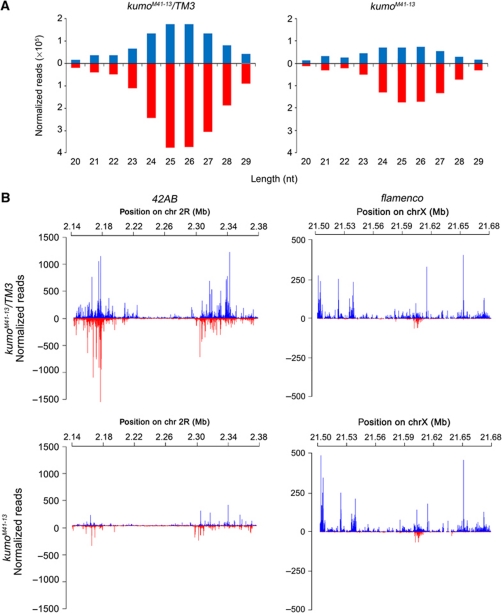

The kumo mutation ablates germline piRNA production

To investigate if the reduction in piRNA levels caused the derepression of transposons in kumo mutant ovaries, we performed deep sequencing analysis of small RNAs from the control and kumo mutant ovaries. The sequencing data were filtered for small RNAs that resulted from RNA degradation and were normalized to endo-siRNAs, which are not related to the piRNA pathway (Malone et al, 2009) (see Supplementary Materials and Methods for details). In Drosophila, the size of piRNAs range from 23 to 29 nt in length. We observed an ∼65% decrease in the amount of 23- to 29-nt small RNAs those match to piRNA clusters and transposons in the kumo mutant (Figure 4A). The majority of the genome-mapping piRNAs in Drosophila arises from a few discrete clusters in the genome called ‘piRNA clusters’, which contain several imperfect copies of transposons and assume pericentromeric and subtelomeric positions (Brennecke et al, 2007; Malone et al, 2009). The bidirectional clusters that give rise to piRNAs from both strands are predominantly active in the germline, kumo mutations resulted in a global reduction in piRNAs from these clusters (Supplementary Table SIII). We observed a 60.2% reduction in the number of piRNAs matching the plus strands and an 87% reduction in the number of piRNAs matching the minus strands of the clusters. The piRNAs originating from the cluster at 42AB on chromosome 2R, which produces ∼30% of the genome-mapping piRNA population (Brennecke et al, 2007), were greatly reduced in kumo mutants, with a 73.5% decrease in the number of piRNAs matching the plus strand and an 80.1% decrease in the number of piRNAs matching the minus strand (Figure 4B; Supplementary Table SIII). Notably, we observed a slight reduction in the number of piRNAs mapping to the plus strand of clusters 14–20; however, the number of piRNAs matching the minus strand of these clusters was severely reduced (Supplementary Table SIII). The number of piRNAs matching to an uni-strand piRNA cluster on X chromosome, cluster 2, was reduced by 30% in kumo mutants. However, no significant reduction in the number of piRNAs arising from the major somatic piRNA cluster flamenco, which is important for repression of the gypsy and ZAM family of transposons in somatic cells, was observed (Figure 4B; Supplementary Table SIII) (Prud’homme et al, 1995; Sarot et al, 2004; Malone et al, 2009). The deep sequencing analysis revealed a requirement of kumo for the production of piRNAs from the clusters involved in transposon suppression in the germline.

Figure 4.

Reduction of germline piRNA levels in kumo mutants. (A) Length histogram of sense and antisense small RNAs produced in the kumo mutant and the control ovaries. An ∼65% reduction in the number of 23–29 nt RNAs was observed in the kumo mutant compared with the control. (B) Diagrams showing piRNA mapping following normalization to a bidirectional cluster at 42AB on chromosome 2R and to unidirectional cluster flamenco on chromosome X. piRNA mapping to the plus strand (blue) and minus strand (red) over cluster 42AB is dramatically reduced in the kumo mutant compared with that in the control ovaries. No such significant reduction in piRNA mapping to the plus strand in the flamenco cluster is observed.

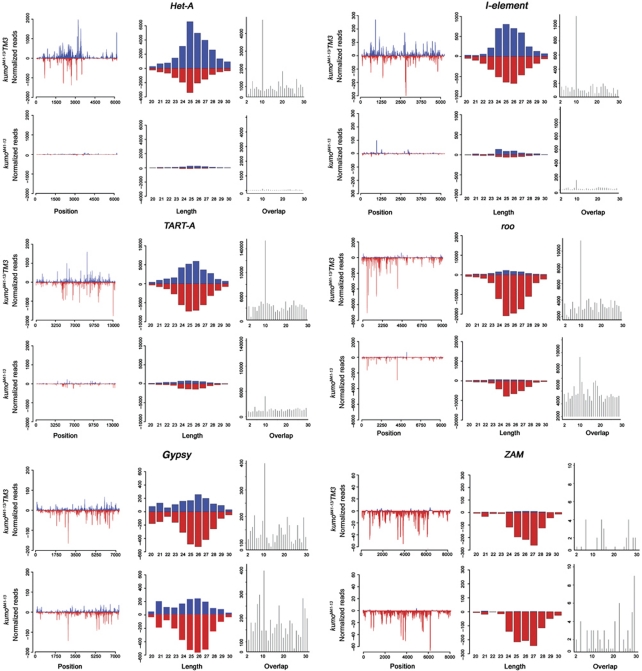

We next investigated the impact of the kumo mutation on piRNAs against transposons by mapping the piRNA reads to canonical transposon sequences, 95 of which were found to be targeted by piRNAs (Supplementary Table SIV). The kumo mutation led to a 70–96% reduction in the number of piRNAs matching to 33% of these elements. More than 58% of transposon families showed at least 50% reduction in the number of matching piRNAs. This suggests that the kumo mutation results in the loss of piRNA matching to a majority of transposons. We found a significant reduction in the number of piRNAs matching in both the sense and antisense orientation to transposons that are predominantly expressed in germline, such as HeT-A, TART-A, I-element and Rt1b. We observed an ∼94% reduction in the number of both the sense and antisense piRNAs for HeT-A and an 80 and 86% reduction in the number of sense and antisense piRNAs, respectively, for I-element. We also observed an 89.2 and 90.5% decrease in the number of sense and antisense piRNAs, respectively, for Rt1b in kumo mutants (Figure 5; Supplementary Table SIV). However, only a modest reduction in the number of sense and antisense piRNAs for roo (34 and 49%, respectively) was observed in kumo mutants. Significantly, the reduction in the number of piRNAs matching to transposons described above correlates to the respective derepression of these transposons, as the expression levels of HeT-A, I-element and TART were dramatically increased in the kumo mutant, while the derepression of roo was not as high (Figure 5). The number of piRNAs matching to 412, mdg1 and stalker4, having both germline and somatic components, was also moderately reduced (Malone et al, 2009) (Supplementary Figure S9). Although we observed a derepression of blood in the kumo mutant ovaries, overall levels of piRNAs corresponding to blood and a few transposons, such as stalker, stalker2, mdg3 and mclintock, were not reduced, which is consistent with the observations in the other piRNA pathway mutants, rhino (rhi) and krimp (Klattenhoff et al, 2009; Malone et al, 2009) (Supplementary Table SIV; Supplementary Figure S9).

Figure 5.

Reduction of piRNA mapping to transposons in kumo mutant ovaries. Mapping of piRNAs to the sense (blue) and antisense (red) strand plotted over the consensus sequence of various transposon families (left panel); length histogram (right) of all matching RNAs from 20 to 30 nt to sense (blue) and antisense (red) strands; and distribution of overlapping piRNAs (right panel) for 1–30 nt. Loss of kumo function depletes piRNA mapping to the sense and antisense strands of Het-A, I-element and TART-A. Concomitantly, piRNA pairs overlapping with 10 nt of those transposons were almost lost in kumo mutant ovaries. A milder reduction in the amount of piRNAs matching to the antisense strand and having a 10-nt overlap was observed for roo. However, for the transposons targeted by somatic piRNAs, a modest reduction in the number of antisense piRNAs mapping to gypsy and no significant difference in piRNAs levels mapping to ZAM were observed in the kumo mutant.

We also analysed sense and antisense piRNAs with an overlap of 10 nt, which are generated by the secondary piRNA pathway, also known as the ping-pong amplification loop. The kumo mutation causes a significant reduction in the number of piRNA that overlap by 10 nt for transposons predominantly expressed in the germline (Het-A, I-element, TART and Rt1b) and a slight reduction for those expressed in both germline and somatic cells (412, mdg1 and stalker4) (Malone et al, 2009), which reveals the necessity of kumo for the ping-pong amplification cycle (Figure 5; Supplementary Figure S9). However, we observed a small reduction in 10-nt overlapping species for roo and no significant reduction of those for a group of transposons including blood, mdg3 and mclintock in kumo mutant ovaries (Supplementary Figure S9). We also observed an overall increase in the piRNAs those match to sense strand of blood, mgd3 and mclintock in the kumo mutant ovaries. Such an increase of sense piRNAs results in a significant loss of the 10-nt overlap bias of blood piRNAs in the kumo mutant, indicating a requirement of kumo for the production of a subset of the ping-pong-derived blood piRNAs. However, no significant change in the 10-nt bias was observed for mdg3 and mclintockin kumo mutants, suggesting that the production of the ping-pong piRNAs for these transposons may be independent of kumo. Next, we analysed piRNAs matching to transposons that are targeted by somatic piRNAs. Antisense piRNAs corresponding to gypsy exhibited a modest decrease of 20% in kumo mutant ovaries, while no significant decrease in the number of piRNA matching to ZAM was observed (Figure 5). Combined with the reduction of Piwi and delocalization of the germline piRNA pathway components in kumo mutant ovaries, the piRNA analysis confirmed the importance of kumo for the production of piRNAs derived from both the primary and ping-pong pathways but not for somatic piRNA production.

Kumo physically interacts with Vas, SpnE, Aub and Piwi

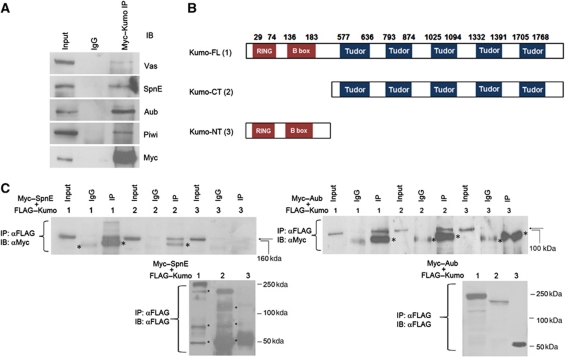

Our results suggested an essential requirement of kumo for the production of germline piRNAs. To gain further insight into the molecular function of Kumo, we examined Kumo interaction with other nuage components that are involved in germline piRNA production. Immunoprecipitation of full-length Myc–Kumo from ovarian lysates also pulled down Vas, SpnE, Aub and Piwi (Figure 6A), suggesting that Kumo is present in a complex with these piRNA pathway components via either a direct or indirect interaction. However, the miRNA pathway protein Ago1, which is not related to the piRNA pathway, did not co-immunoprecipitate with Myc–Kumo (Supplementary Figure S10A). We further investigated if Kumo interacts directly with SpnE, which is close to kumo in the hierarchy of nuage organization and Aub, which is a germline Piwi family protein directly involved in piRNA production. We detected FLAG–Kumo interactions with SpnE and Aub in S2 cells, indicating that these proteins can interact even in the absence of germline factors, possibly by a direct interaction (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Kumo physically interacts with Vas, SpnE, Aub and Piwi and its interaction with SpnE and Aub is mediated by tudor domains. (A) Western blots showing the co-immunoprecipitation of full-length Myc–Kumo with Vas, Aub, SpnE and Piwi from ovarian lysate. (B) Schematic diagram showing the Kumo variants tagged with FLAG transfected into S2 cells. Kumo-FL, full-length Kumo; Kumo-CT, harbouring all five tudor domains; and Kumo-NT, harbouring RING and B-box domains. (C) Western blots showing the co-immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged Kumo variants with Myc–Aub and Myc–SpnE using S2 cell lysate. Both Aub and SpnE are immunoprecipitated with FL- and CT-Kumo but not with NT-Kumo and the control IgG. (Lower panels) Western blots with anti-FLAG showing all examined Kumo variants efficiently pulled down. Asterisks denote nonspecific bands.

To study the role of the RING, B-box and tudor domains of Kumo in mediating these interactions, FLAG-tagged Kumo variants containing only RING and B-box (Kumo-NT) or tudor domains (Kumo-CT) were separately transfected into S2 cells with either Myc–SpnE or Myc–Aub (Figure 6B). Myc–SpnE and Myc–Aub were successfully pulled down with Kumo-CT but not with Kumo-NT (Figure 6C), which suggests that the tudor domains of Kumo are sufficient to mediate interactions with Aub and SpnE. Recently, it has been shown that certain tudor domain proteins interact with Piwi family proteins at sDMAs (Kirino et al, 2009; Nishida et al, 2009). Therefore, we examined whether the interaction of Kumo and Aub is dependent on the sDMA of Aub. A mutated Aub in which the four arginine residues at the N-terminus were changed to lysine to abolish sDMA (Patil and Kai, 2010) was efficiently co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG–Kumo (Supplementary Figure S10B), suggesting that the Aub–Kumo interaction is not dependent on the sDMA of Aub at the four arginine residues in S2 cells.

To examine the roles of the RING, B-BOX and tudor domains of Kumo in nuage organization and transposon derepression in vivo, Kumo-NT and Kumo-CT transgenes were expressed in the germline cells of kumo mutant ovaries. Kumo-NT had a dispersed localization in the cytoplasm and did not rescue female sterility (Supplementary Table SIA). In addition, Vas, Tej, Krimp and Aub remained mislocalized as discrete cytoplasmic foci (Supplementary Figure S11A). Kumo-CT expressed in kumo mutant germline cells also remained dispersed in the cytoplasm, although it rescued sterility to some extent (hatching rate of 46.14% compared with the 75.5% rescue by Kumo; Supplementary Table SIA). Vas, Tej, Krimp and Aub mostly returned to the perinuclear region, although a few discrete cytoplasmic foci were discernible. Furthermore, the expression of Kumo-CT but not Kumo-NT rescued the derepression of HeT-A, TART and roo to a greater extent in kumo mutant ovaries (Supplementary Figure S11B). Therefore, our results suggest that the tudor domains of Kumo are necessary for the interaction with the other nuage components, the integrity of the nuage and the repression of transposons. The partial rescue of sterility by Kumo-CT probably results from nuage reorganization and transposon repression. The rescue experiments also suggest that the RING and B-box domains may be dispensable or that they may play a supportive role in interactions with other nuage components and in transposon repression.

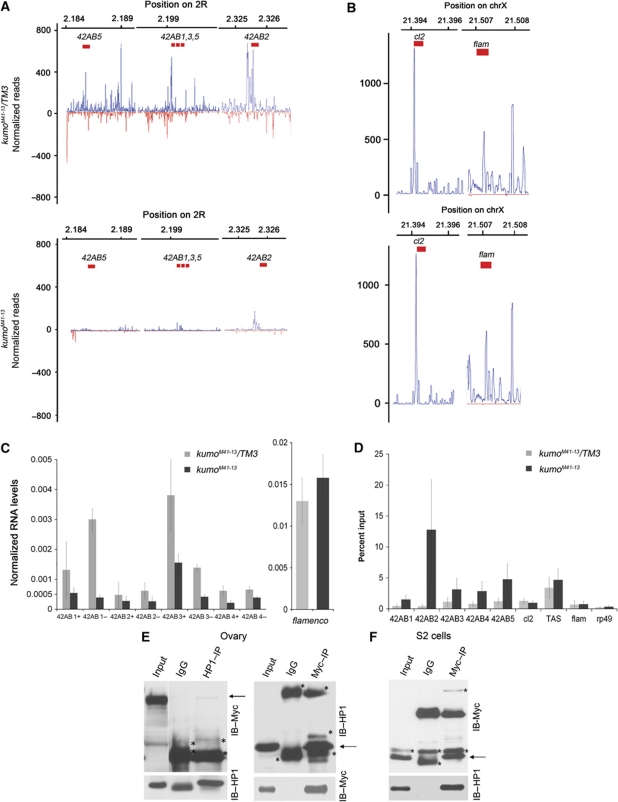

The kumo mutation results in reduction of cluster transcription

Kumo, which is involved in nuage organization and piRNA production, also localizes to the nucleus in the germarium (Figure 1G). To identify a potential nuclear function of kumo, we investigated if kumo is also involved in the production of precursor piRNAs, which are processed into piRNAs, from the germline piRNA clusters. A recent study in Drosophila revealed longer transcripts produced from both strands of the piRNA cluster 42AB (Klattenhoff et al, 2009). We analysed bidirectional transcription from the 42AB cluster using strand-specific quantitative RT–PCR (Figure 7A and B) using the same primers as described by Klattenhoff et al (2009), in addition to some in-house designed primers. The qRT–PCR confirmed robust transcription from the examined regions in wild-type ovaries, whereas transcription from both the plus and minus strands was reduced in the kumo mutant ovaries (Figure 7C). At region A within the 42AB piRNA cluster, we observed a 2.4- and 7.6-fold decrease in the RNA levels from the plus and minus strands, respectively (42AB1, designated in Figure 7A). Expression levels from both strands were also modestly reduced at two other loci near region A (42AB3 and 42AB4) in kumo mutants. Similarly, a 1.7- and 2.3-fold decrease in the RNA levels from plus and minus strands, respectively, were also observed at regions 1–32 of the 42AB cluster in kumo mutant ovaries (42AB2). Significantly, the expression levels of long transcripts from the somatic piRNA cluster flamenco were unaffected in kumo mutant ovaries, indicating a specific defect in transcription from germline piRNA clusters. However, a significant impact on cluster transcription was not observed in the krimp and tej mutant ovaries (Supplementary Figure S12). Because the reduction in cluster transcription in the kumo mutant ovaries was moderate, kumo may play only a supportive role for precursor piRNA transcription and/or accumulation.

Figure 7.

The kumo mutation results in reduced cluster transcription and high HP1 occupancy at piRNA clusters. (A, B) Mapping of piRNAs to the indicated regions of the bidirectional cluster at 42AB and the unidirectional clusters at X (cluster 2 and flamenco), which were examined for the expression of the cluster transcripts and HP1 binding. In the kumo mutant ovaries, piRNA mapping to the bidirectional cluster were nearly eliminated, whereas no significant impact was observed in the number of piRNAs matching cluster 2 and flamenco. (C) Strand-specific quantitative RT–PCR showing the expression levels of cluster transcripts from the plus and minus strands (indicated by + and −, respectively) from the 42AB piRNA cluster. RNA levels from both strands in the kumo mutant ovaries are reduced compared with those in the heterozygous control. However, no significant difference in the expression levels of transcripts from a region of the flamenco piRNA cluster was observed between the control and kumo mutant ovaries. Error bars indicate standard error for three independent experiments. (D) Quantification of chromatin immunoprecipitation with anti-HP1 using primers at various regions of the 42AB piRNA cluster in control and kumo mutant ovaries. The percent input of immunoprecipitates is shown for each primer set. HP1 binding was enriched in kumo mutant ovaries compared with that in the kumo heterozygous controls with 1.5-, 12.8-, 3.1-, 2.8- and 4.8-fold increases at 42AB1–5, respectively. No significant increase was observed at unidirectional piRNA clusters, cluster 2 and flamenco, the controls, euchromatin region, rp49 and heterochromatin region (X-TAS) in the kumo mutant. Error bars indicate standard error from two independent experiments. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation of Myc–Kumo and HP1 from the ovarian lysates. Western blots for Myc–Kumo and HP1: 5% of input was loaded on the blots to detect HP1 in Myc–Kumo immunoprecipitate and in the reciprocal immunoprecipitation 1% of input was used. (F) HP1 is co-immunoprecipitated with Myc–Kumo in S2 cells. 1% input was used in the western blot. Asterisks denote the non-specific bands.

Rhi, a HP1 homologue expressed in the germline, is required for production of cluster transcripts (Klattenhoff et al, 2009). However, the exact mechanism of how rhi promotes cluster transcription remains unknown. To study if Kumo functions for cluster transcription via Rhi, we examined the interaction of Kumo and Rhi by immunostaining and co-immunoprecipitation. Immunostaining revealed few juxtaposed Kumo and Rhi foci; however, we did not observe a significant number of overlapping foci (Supplementary Figure S13A). Furthermore, Rhi did not co-immunoprecipitate with Myc–Kumo from ovarian lysates (Supplementary Figure S13B), suggesting that Rhi and Kumo are not present in the same complex.

Kumo is involved in the epigenetic regulation of piRNA clusters via HP1

The reduction in cluster transcription from germline piRNA clusters in kumo mutant ovaries prompted us to examine if Kumo directly binds to piRNA clusters. However, we failed to detect any Myc–Kumo binding to the regions of piRNA cluster at 42AB, where reduction of potential piRNA precursors was detected in kumo mutant ovaries (Supplementary Figure S14). This finding suggests that Kumo probably does not bind directly to germline piRNA clusters to regulate the expression of cluster transcripts. We searched for any obvious changes in chromatin state in kumo mutants by immunostaining. The expression patterns of di- and tri-methylated H3K9, which are markers of silent chromatin, were not significantly different between the kumo mutant and control germline cells (Supplementary Figure S15). However, we observed a higher expression of the heterochromatin marker HP1 in the kumo mutant ovaries, especially in the germarium (Supplementary Figure S16A). The high expression of HP1 in the kumo mutant during early stages of germline development was confirmed by quantitative western analysis using the lysates prepared from germarium and early-stage egg chambers (Supplementary Figure S16B). Recent studies have shown increased HP1 binding to the piRNA/endo-siRNA clusters in the somatic cells of piRNA/endo-siRNA pathway mutants (Yin and Lin, 2007; Moshkovich and Lei, 2010). This prompted us to investigate if HP1 occupancy is increased at germline piRNA clusters in kumo mutant ovaries, which could possibly cause the observed reduction in cluster transcription.

In the kumo mutant ovaries, chromatin immunoprecipitation for HP1 showed an increase in HP1 binding at the regions of the 42AB piRNA cluster for which bidirectional transcription was examined (Figure 7D). In contrast, no significant difference in the HP1 occupancy at the Cluster 2 and flamenco piRNA clusters was observed between the kumo heterozygous and the mutant ovaries. HP1 binding at the euchromatic locus rp49 and at the heterochromatic TAS region was also comparable between the control and the mutant ovaries.

Next, we examined whether Kumo directly or indirectly regulates HP1 binding at piRNA clusters by examining the HP1 interaction with Kumo. HP1 was immunoprecipitated with Myc–Kumo in ovarian lysates. The interaction between HP1 and Kumo, in the ovaries, was also confirmed through a reciprocal experiment by immunoprecipitating HP1 (Figure 7E), indicating that Kumo and HP1 are present in the same complex. Furthermore, endogenous HP1 could be immunoprecipitated with FLAG–Kumo in S2 cells (Figure 7F), suggesting that the Kumo and HP1 interaction does not require any germline factors and probably is a direct interaction. High HP1 binding specifically at germline piRNA clusters in the kumo mutant suggests that Kumo may restrict HP1 binding at piRNA clusters, which is probably required to facilitate transcription from piRNA clusters. These results suggest that Kumo may be part of a pathway that facilitates cluster transcription by restricting HP1 binding to piRNA clusters.

Discussion

The nuage is a characteristic structure found in animal germline cells and it has been proposed to function as the site of piRNA processing in the germline. In this study, we characterize kumo, a Drosophila homologue of the mammalian Tdrd4/RNF17. Both Kumo and RNF17 have five tudor domains and an N-terminal RING domain; Kumo also has two B-box domains near the N-terminal RING motif that are absent in RNF17. RNF17/Tdrd4 does not co-localize with other nuage components, such as Tdrd1, and its role in piRNA production remains elusive (Pan et al, 2005). We demonstrate that Kumo localizes to the nuage and is involved in germline piRNA production in Drosophila. Similar to other piRNA pathway components in Drosophila, kumo is also important for the establishment of polarity, oocyte fate determination and karyosome compaction (Chen et al, 2007; Lim and Kai, 2007; Pane et al, 2007; Patil and Kai, 2010), However, the defect in oocyte maintenance is more severe in kumo mutants than in other piRNA pathway component mutants. Therefore, kumo may be required for oocyte maintenance in a piRNA-independent manner.

Our results suggest that kumo plays a critical role in anchoring all piRNA pathway components to the nuage. The presence of Kumo in the same complex with Vas, Aub and SpnE in the ovary (Figure 6A) supports its role in the maintenance of the macromolecular complex at the nuage. Our study also demonstrates that the tudor domains of Kumo mediate the interaction with other nuage components, which is possibly essential for their localization at the perinuclear nuage (Figure 6C; Supplementary Figure S11A). Furthermore, the Kumo-CT transgene also rescues the derepression of transposons and sterility to a large extent (Supplementary Figure S11B). However, it also may be possible that a modest amount of Kumo-CT is present at the perinuclear nuage. This finding also adds to the accumulating body of evidence that nuage assembly in the cytoplasm and transposon repression, are co-dependent processes. RING and B-Box domains alone could not rescue the localization of other piRNA pathway components, transposon derepression or sterility. However, these domains may not be completely dispensable for Kumo function because Kumo-CT cannot fully rescue the defects in the localization of other nuage components or sterility in the loss-of-function allele (Supplementary Figure S11). Furthermore, Kumo-CT is not sufficient to form perinuclear foci, indicating that RING and B-box domains contribute to some extent to Kumo function.

Consistent with defects in the repression of transposons targeted by germline piRNAs in the kumo mutant, deep sequencing analysis revealed a significant decrease in the production of piRNAs from germline dual-strand piRNA clusters but not from somatic piRNA clusters (Figure 4B; Supplementary Table SIII). These data further support the specificity of nuage functions in the germline piRNA pathway. Also, kumo mutant ovaries show a significant reduction in the amount of antisense piRNAs transcribed from dual-strand clusters, which include the piRNAs that initiate ping-pong amplification. The importance of kumo for ping-pong amplification was strongly supported by a severe reduction in piRNA pairs with a 10-nt overlap for many reteroelements. In addition, we did not observe any reduction of sense–antisense piRNA pairs with 10-nt overlap for transposons blood, mclintock and mdg3 due to an increase in the sense piRNAs of those transposons in the kumo mutant ovaries. A similar profile for blood and other transposons has been reported in the rhi mutant (Klattenhoff et al, 2009). These results suggest that the production of a subset of piRNAs for these transposon families may be independent of kumo and other piRNA pathway components (Figure 5; Supplementary Figure S9).

The presence of kumo in the nucleus probably is required for efficient transcription of clusters. In fact, kumo mutants exhibited a modest decrease in the production of the cluster transcripts and a concomitant increase in HP1 occupancy at the 42AB cluster (Figure 7C and D), suggesting that kumo may function to counteract heterochromatin spread via the sequestration of HP1. An active opposition to HP1 spread at piRNA/endo-siRNA loci was demonstrated by Moshkovich and Lei (2010), who showed increased HP1 occupancy with the transcriptional repression at piRNA/endo-siRNA loci in somatic cells of piRNA and endo-siRNA pathway component mutants. Alternatively, the kumo mutation may result in the loss of piRNA precursor processing or the failure of piRNA loading onto Piwi family proteins. In the absence of kumo function, these free precursors or piRNAs may lead to a negative feedback loop, thereby causing a reduction in cluster transcription and the subsequent spread of heterochromatin.

The modest reduction in the amount of cluster transcripts in kumo mutants alone does not appear to account for the dramatic decrease in germline piRNA levels. Indeed, the reduction in the cluster transcription levels in kumo mutant ovaries was not significant compared with the rhi mutant (Klattenhoff et al, 2009), implying that the reduction of piRNA levels in the kumo mutant could be mainly due to defects in the processing steps at the cytoplasmic nuage in kumo mutant ovaries. Kumo is required for the localization of all of the examined nuage components, suggesting an essential role of Kumo for nuage assembly and for ensuring the processing of piRNAs in cytoplasm of the germline cells. The cytoplasmic nuage foci containing Kumo can be observed throughout oogenesis, except in oocytes, similar to the localization of other nuage proteins. However, Kumo stays in the nucleus only in the germarium, which is a brief window during female germline development. This observation supports a mechanism by which the production of germline piRNA precursors and their subsequent processing into piRNAs may be regulated during germline development in Drosophila.

We propose that Kumo has multiple functions in distinct subcellular localizations that may occur in a stage-dependent manner. Kumo appears to elicit cluster transcription in the germarium and also contributes to the processing of piRNA in the nuage. In later stages, however, Kumo may predominantly function in the processing of piRNAs in the nuage. The molecular mechanism by which Kumo or any other nuage component exerts its cytoplasmic function at the nuage in the production of germline piRNAs remains elusive.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks

All fly stocks were maintained at 25°C. The fly stocks used were aubN11/HN2, vasPH165, spnEE616/hls3987, tej48-5, krimpf06583, ago3t2/t3 and maelM391/Df(3L)79E-F, kumoM41-13. Either kumoM41-13/TM3 or y w was used as control (see Supplementary data for generation of kumoM41-13 allele and transgenic strains).

Immunostaining

Immunostaining of the ovaries was performed as described previously (Lim and Kai, 2007). The antibodies used for immunostaining in the study are as follows: rabbit anti-Kumo polyclonal (1:1000), rabbit anti-Tej (1:1000), mouse anti-Lamin monoclonal clone ADL67.10 (Hybridoma bank, Iowa) (1:5), guinea pig anti-Vas polyclonal (1:1000), rat anti-SpnE polyclonal (1:200), mouse anti-Aub and anti-Ago3 (1:1000) (kind gift from Dr Siomi), rabbit anti-Krimp (1:10 000), guinea pig anti-Mael (1:500), mouse anti-Piwi (a kind gift from Dr Siomi) mouse anti-Gurken 1D12 (1:10) (Hybridoma bank, Iowa), rat anti-Osk (1:100) (a gift from Paul Lasko), guinea pig anti-C(3)G (1:500) (kind gift from Dr Scott Hawley), mouse monoclonal HP1, C1A9 (1:50) (Hybridoma bank, Iowa), mouse anti-Myc (1:1000) (Sigma Aldrich) and mouse anti-Ste (1:50) (a gift from Dr Maria Bozzetti). Secondary antibodies used in the study were Alexa Fluor -488, -555, or -633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, anti-rat anti-guinea pig IgG (1:400) (Molecular Probes). Images were acquired using LSM5 Exciter confocal microscope.

Northern blotting

Northern blot analysis to detect Kumo transcript was performed as described previously by Lim and Kai (2007). Briefly, 1 μg of polyA RNA was run on the formaldehyde/MOPS 1% agarose gel and transferred on to a Hybond N+ membrane. Probe was synthesized by in-vitro transcription using T3 and SP6 RNA polymerase in the presence of [γ32P]UTP (3000 Ci/mmol, 10 mCi/ml). Hybridization was performed at 62°C as previously described by Patil and Kai (2010).

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation in S2 cells and ovaries was performed as described previously (Patil and Kai, 2010) with minor modifications. Briefly, S2 cells were lysed in IP buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaF, 0.05% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Lysates were preabsorbed with protein A/G beads (Calbiochem) before incubation with antibody-conjugated beads overnight. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times, and proteins were eluted from the beads at 95°C in SDS buffer (see Supplementary data for details about constructs used). For IP experiment in ovaries, roughly 300 ovaries were homogenised in IP buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.1% NP40) supplemented with the protease inhibitor cocktail. The antibodies used were guinea pig anti-Vasa (1:5000), rat anti-SpnE (1:1000), mouse anti-Aub (1:5000) (a kind gift from Dr Siomi), mouse anti-Myc (1:5000, Sigma), mouse anti-FLAG (1:1000, Sigma) and mouse anti-HP1 (1:50, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Input corresponded to 0.1–1.0% of lysates.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed as described by Pek et al (2009), using the ChIP assay kit (Millipore), with few modifications. Ovaries dissected from 150 females of each genotype were used for one assay. Ovaries were subjected to sonication, and chromatin was crosslinked to proteins with 1.8% formaldehyde. Lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-Myc (1:1000, Sigma) or anti-HP1 (1:50, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). DNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform extraction.

Accession numbers

Small RNA libraries are deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus and can be accessed with accession number GSE34728.

Note added in proof

Recently Zhang et al reported a complementary analysis on the same gene, which they name as qin. (Zhang Z, Xu J, Koppetsch BS, Wang J, Tipping C, Ma S, Weng Z, Theurkauf WE, Zamore PD (2011) Molecular Cell 44: 572–584.)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank MC Siomi, William Theurkauf, MP Bozzetti, P Lasko, RS Hawley, D St Johnston, Dahua Chen, the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for reagents and fly stocks. We thank Kai laboratory members for their kind assistance and the discussions, Lim MiahKyan for the generation of kumoM41-13, and Joanne Yew for critical reading. We also thank Dr Allan Spradling in whose laboratory at the Department of Embryology, Carnegie Institution. This work was initiated with support from HHMI. We are grateful to KR Govindrajan in TemasekLife Sciences Laboratory, Shinpei Kawaoka in Tokyo University and Arun Khattri in the Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, for their help in bioinformatics analysis. This work was supported by Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory and the Singapore Millennium Foundation.

Author contributions: AA and TK conceived and conducted the experiments, analysed the data and prepared the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

02/15/2012

Since Advance Online Publication, this article has had the additional paragraphs ‘Note added in proof’ and ‘Accession numbers’ added at the end of the Materials and methods section.

References

- Aravin AA, Klenov MS, Vagin VV, Bantignies F, Cavalli G, Gvozdev VA (2004) Dissection of a natural RNA silencing process in the Drosophila melanogaster germ line. Mol Cell Biol 24: 6742–6750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin AA, Naumova NM, Tulin AV, Vagin VV, Rozovsky YM, Gvozdev VA (2001) Double-stranded RNA-mediated silencing of genomic tandem repeats and transposable elements in the D. melanogaster germline. Curr Biol 11: 1017–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Aravin AA, Stark A, Dus M, Kellis M, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ (2007) Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell 128: 1089–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Pane A, Schupbach T (2007) Cutoff and aubergine mutations result in retrotransposon upregulation and checkpoint activation in Drosophila. Curr Biol 17: 637–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy EM (1974) Fine structural observations on the form and distribution of nuage in germ cells of the rat. Anat Rec 178: 731–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley SD, Tamanaha M, Clegg NJ, Ruohola-Baker H (2003) Maelstrom, a Drosophila spindle-class gene, encodes a protein that colocalizes with Vasa and RDE1/AGO1 homolog, Aubergine, in nuage. Development 130: 859–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Reyes A, Elliott H, St Johnston D (1995) Polarization of both major body axes in Drosophila by gurken-torpedo signalling. Nature 375: 654–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardane LS, Saito K, Nishida KM, Miyoshi K, Kawamura Y, Nagami T, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2007) A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5′ end formation in Drosophila. Science 315: 1587–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh JR, St Johnston D (2004) The origin of asymmetry: early polarisation of the Drosophila germline cyst and oocyte. Curr Biol 14: R438–R449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai T, Williams D, Spradling AC (2005) The expression profile of purified Drosophila germline stem cells. Dev Biol 283: 486–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana JS, Theurkauf W (2010) piRNAs, transposon silencing, and Drosophila germline development. J Cell Biol 191: 905–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino Y, Kim N, de Planell-Saguer M, Khandros E, Chiorean S, Klein PS, Rigoutsos I, Jongens TA, Mourelatos Z (2009) Arginine methylation of Piwi proteins catalysed by dPRMT5 is required for Ago3 and Aub stability. Nat Cell Biol 11: 652–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff C, Bratu DP, McGinnis-Schultz N, Koppetsch BS, Cook HA, Theurkauf WE (2007) Drosophila rasiRNA pathway mutations disrupt embryonic axis specification through activation of an ATR/Chk2 DNA damage response. Dev Cell 12: 45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff C, Xi H, Li C, Lee S, Xu J, Khurana JS, Zhang F, Schultz N, Koppetsch BS, Nowosielska A, Seitz H, Zamore PD, Weng Z, Theurkauf WE (2009) The Drosophila HP1 homolog Rhino is required for transposon silencing and piRNA production by dual-strand clusters. Cell 138: 1137–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Vagin VV, Lee S, Xu J, Ma S, Xi H, Seitz H, Horwich MD, Syrzycka M, Honda BM, Kittler EL, Zapp ML, Klattenhoff C, Schulz N, Theurkauf WE, Weng Z, Zamore PD (2009) Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell 137: 509–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L, Diehl-Jones W, Lasko P (1994) Localization of vasa protein to the Drosophila pole plasm is independent of its RNA-binding and helicase activities. Development 120: 1201–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim AK, Kai T (2007) Unique germ-line organelle, nuage, functions to repress selfish genetic elements in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 6714–6719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald AP (1968) Polar granules of Drosophila. II. Ultrastructural changes during early embryogenesis. J Exp Zool 167: 237–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Brennecke J, Dus M, Stark A, McCombie WR, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ (2009) Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell 137: 522–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Hannon GJ (2009) Small RNAs as guardians of the genome. Cell 136: 656–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshkovich N, Lei EP (2010) HP1 recruitment in the absence of argonaute proteins in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 6: e1000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida KM, Okada TN, Kawamura T, Mituyama T, Kawamura Y, Inagaki S, Huang H, Chen D, Kodama T, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2009) Functional involvement of Tudor and dPRMT5 in the piRNA processing pathway in Drosophila germlines. EMBO J 28: 3820–3831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page SL, Hawley RS (2001) c(3)G encodes a Drosophila synaptonemal complex protein. Genes Dev 15: 3130–3143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Goodheart M, Chuma S, Nakatsuji N, Page DC, Wang PJ (2005) RNF17, a component of the mammalian germ cell nuage, is essential for spermiogenesis. Development 132: 4029–4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pane A, Wehr K, Schupbach T (2007) zucchini and squash encode two putative nucleases required for rasiRNA production in the Drosophila germline. Dev Cell 12: 851–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil VS, Kai T (2010) Repression of retroelements in Drosophila germline via piRNA pathway by the tudor domain protein Tejas. Curr Biol 20: 724–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pek JW, Lim AK, Kai T (2009) Drosophila maelstrom ensures proper germline stem cell lineage differentiation by repressing microRNA-7. Dev Cell 17: 417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme N, Gans M, Masson M, Terzian C, Bucheton A (1995) Flamenco, a gene controlling the gypsy retrovirus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 139: 697–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Inagaki S, Mituyama T, Kawamura Y, Ono Y, Sakota E, Kotani H, Asai K, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2009) A regulatory circuit for piwi by the large Maf gene traffic jam in Drosophila. Nature 461: 1296–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Nishida KM, Mori T, Kawamura Y, Miyoshi K, Nagami T, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2006) Specific association of Piwi with rasiRNAs derived from retrotransposon and heterochromatic regions in the Drosophila genome. Genes Dev 20: 2214–2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarot E, Payen-Groschene G, Bucheton A, Pelisson A (2004) Evidence for a piwi-dependent RNA silencing of the gypsy endogenous retrovirus by the Drosophila melanogaster flamenco gene. Genetics 166: 1313–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlake T, Bode J (1994) Use of mutated FLP recognition target (FRT) sites for the exchange of expression cassettes at defined chromosomal loci. Biochemistry 33: 12746–12751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senti KA, Brennecke J (2010) The piRNA pathway: a fly's perspective on the guardian of the genome. Trends Genet 26: 499–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi MC, Mannen T, Siomi H (2010) How does the royal family of Tudor rule the PIWI-interacting RNA pathway? Genes Dev 24: 636–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA (2011) PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 246–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin VV, Sigova A, Li C, Seitz H, Gvozdev V, Zamore PD (2006) A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science 313: 320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Lin H (2007) An epigenetic activation role of Piwi and a Piwi-associated piRNA in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 450: 304–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.