Abstract

NOTCH1 is frequently mutated in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL), and can stimulate T-ALL cell survival and proliferation. Here we explore the hypothesis that Notch1 also alters T-ALL cell migration. Rho GTPases are well-known to regulate cell adhesion and migration. We have analysed the expression levels of Rho GTPases in primary T-ALL samples compared to normal T cells by quantitative PCR. We found that 5 of the 20 human Rho genes are highly and consistently upregulated in T-ALL, and 3 further Rho genes are expressed in T-ALL but not detectably in normal T cells. Of these, RHOU expression is highly correlated with the expression of the Notch1 target DELTEX-1. Inhibition of Notch1 signalling with a γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) or Notch1 RNAi reduces RhoU expression in T-ALL cells, whereas constitutively active Notch1 increased RhoU expression. In addition, Notch1 or RhoU depletion, or GSI treatment, inhibits T-ALL cell adhesion, migration and chemotaxis. These results indicate that NOTCH1 mutation stimulates T-ALL cell migration through RhoU upregulation which could contribute to the leukaemia cell dissemination.

Keywords: Rho GTPases, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Notch1, RhoU, cell migration, cytoskeleton

Introduction

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) is a common cancer in children. T-ALL patients usually present with large numbers of leukaemic blasts with an immature T-cell phenotype in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. Although current ALL treatment protocols have success rate of around 70 to 80% five-year event-free survival in children, T-ALL is associated with a poorer prognosis than B-ALL (1) . Leukaemic blasts can infiltrate numerous tissues, with the central nervous system (CNS) being a frequent site of metastasis (2,3) . CNS relapse in T-ALL requires more aggressive treatment regimens that can lead to secondary malignancies or neurocognitive disorders (4) . A better understanding of the genes involved in the pathogenesis of T-ALL could allow the development of T-ALL therapies that have fewer negative effects on long-term patient health.

Among the genetic alterations that are associated with the development of T-ALL, mutation of the NOTCH1 oncogene is one of the most common, being present in over 50% of cases (5,6) . Notch1 is required for T lineage commitment and regulates T cell maturation in the thymus (7,8) . Notch1 recognises ligands of the Delta and Serrate/Jagged families expressed in the thymic stroma. Ligand binding induces two sequential proteolytic cleavage events. The first cleaves a large portion of the ectodomain, exposing a site recognised by the intramembrane γ-secretase proteolytic complex (GS). Cleavage by GS releases the Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD), which enters the nucleus where it associates with the DNA-binding protein CSL (CBF1/Su(H)/Lag1) and other proteins to regulate transcription of a wide range of genes, including DELTEX-1 and HES1 (9) . NOTCH1 mutations found in T-ALL commonly lead to constitutive Notch1 signalling via ligand-independent NICD production, or enhanced NICD half-life (10) . Constitutive Notch1 signalling promotes leukaemic cell survival and proliferation. Notch1 also regulates expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7, which contributes to CNS metastasis in T-ALL (11) , but whether Notch1 signalling affects other genes that regulate cell motility has not been investigated.

Rho family GTPases control haematopoietic cell morphology, migration and adhesion as well as cell proliferation and differentiation (12,13) . Most Rho GTPases are active when bound to GTP, and inactivated when the bound GTP is hydrolysed to GDP. Signalling through Rho GTPases is therefore controlled by regulatory proteins that modulate GTP binding and hydrolysis, including guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). Twenty Rho family members have been identified in humans, several of which have atypical properties (14) . Rnd1, Rnd2, Rnd3 and RhoH have amino acid substitutions that prevent GTPase catalytic activity, and therefore only exist in a GTP-bound state. RhoBTB1 and RhoBTB2 are much larger than other Rho GTPases, and appear not to bind or hydrolyse GTP (15,16) . RhoU and RhoV are also considered atypical because they have high intrinsic GDP/GTP exchange rates and therefore are likely to be predominantly in the GTP-bound state (16) . Rho proteins act through their downstream effectors to regulate cytoskeletal and adhesion dynamics, and thereby contribute to cell migration. Altered expression of Rho genes or activation of Rho proteins has been reported in a variety of cancer types, and the RhoH gene is mutated in some lymphomas (17,18) . Rho proteins contribute to the enhanced migration and invasion of cancer cells (17,19,20) .

In this study, we have investigated the hypothesis that the pathogenesis of T-ALL involves the altered expression of Rho family genes. We have investigated the mRNA expression of human Rho genes in primary T-ALL leukaemic blast samples and compared it to the expression in normal peripheral blood T cells. We have found that several Rho genes have significantly increased expression in T-ALL, and in particular shown that RhoU expression is regulated by Notch1 signalling.

Results

Atypical Rho genes are upregulated in T-ALL

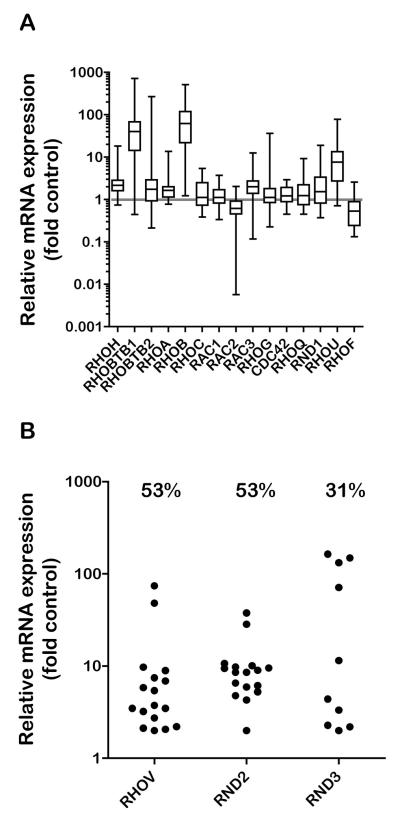

To study Rho GTPase involvement in the pathogenesis of T-ALL we investigated Rho gene expression in 30 primary T-ALL blast samples compared to mature T cells from 5 healthy blood donors. Expression of each Rho gene mRNA was determined by quantitative PCR, using GAPDH as a reference gene (Suppl Fig. 1). Rho mRNA expression for each T-ALL sample was quantified relative to the mean of the control samples (Fig. 1A, Table 1). To determine which of the genes were differentially expressed to a statistically significant degree, a Mann-Whitney test was applied (Table 1), considering the median to be the best representation of the data, which in many cases were skewed and not normally distributed (Fig. 1A). Five Rho genes were significantly upregulated in the T-ALL samples: RHOH, RHOBTB1, RHOA, RHOB and RHOU. RHOA and RHOH were very consistently increased in nearly all the T-ALL samples although the median fold upregulation was quite small. The magnitude of RHOBTB1, RHOB and RHOU upregulation was much higher, but with more variation across the T-ALL samples (Fig. 1A, Table 1). Three genes were not detectable in normal T cell samples but were detected in more than 30% of T-ALL samples: RHOV, RND2 and RND3. We therefore could not determine the fold expression differences relative to normal T cells for these genes, however the variation in expression with T-ALL samples was analysed (Fig. 1B). RHOD was not expressed in normal T-cell or T-ALL samples, and preliminary analysis indicated that RHOJ is also not expressed (data not shown), in agreement with our published data on normal T cells and the CCRF-CEM T-ALL cell line (21) . Interestingly, 5 of the 8 differentially expressed Rho genes (RHOBTB1, RHOU, RHOV, RND2 and RND3) belonged to the atypical sub-class (16) , which was therefore over-represented among the altered genes.

Figure 1. Rho mRNA expression in T-ALL.

A. RNA was extracted from 30 T-ALL blast samples and normal T-lymphocytes from 5 peripheral blood samples of healthy donors. mRNA expression of each Rho gene was measured by quantitative PCR, using GAPDH expression as a reference. Rho gene expression in each T-ALL sample was determined relative to the mean expression of the normal control samples using the comparative CT method. Data are expressed as fold expression relative to control on a logarithmic scale. B. mRNA expression of Rho genes not detected in normal T-lymphocytes. The T-ALL sample with the lowest detected mRNA expression was assigned a relative expression level of 2. Other values are shown relative to this sample. Values above each column indicate the % of T-ALL samples that detectably expressed each gene.

Table 1. Rho mRNA expression in T-ALL relative to healthy controls.

RNA was extracted from 30 T-ALL blast samples and normal T-lymphoblasts from 5 peripheral blood samples of healthy donors. mRNA expression of each Rho gene was measured by qPCR, using GAPDH as a reference gene. GAPDH-normalised Rho expression values (dCT), were used to compare expression levels between normal and T-ALL populations using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test of medians.

| gene | P-value | test summary |

|---|---|---|

| RHOF | 0.079 | ns |

| RHOH | 0.002 | ** |

| RND1 | 0.113 | ns |

| RHOBTB1 | 0.003 | ** |

| RHOBTB2 | 0.218 | ns |

| RHOA | 0.008 | ** |

| RHOB | 0.001 | *** |

| RHOC | 0.437 | ns |

| RAC1 | 0.522 | ns |

| RAC2 | 0.044 | * |

| RAC3 | 0.012 | * |

| RHOG | 0.579 | ns |

| CDC42 | 0.340 | ns |

| RHOQ | 0.579 | ns |

| RHOU | 0.003 | ** |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 and

P < 0.001, ns = not significant.

Rho gene expression patterns cluster T-ALL patients in two groups

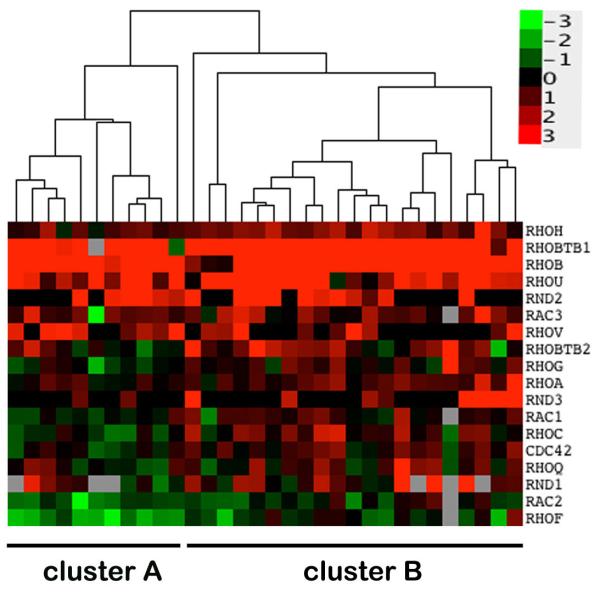

T-ALL samples were grouped according to similarity of Rho expression (fold expression relative to controls) using clustering algorithms. The expression values were visualized in a heat-map, with a dendrogram showing the resulting clusters of T-ALL samples (Fig. 2). This analysis resulted in the resolution of two major clusters of T-ALL patients (denoted clusters A and B). The upregulation of RHOH, RHOBTB1, RHOA, RHOB and RHOU was similar in both clusters, as expected due to the consistency of the changes in these 5 genes across all samples. The distinction between the two groups reflected the expression of genes that showed variable expression across the T-ALL samples. Cluster A was enriched in samples where the expression of several Rho genes was lower than normal controls, including RAC1, RHOC, CDC42 and RHOQ, whereas cluster B had a greater incidence of higher-than-normal expression of these genes. The two Rho expression profile clusters might reflect different patient characteristics. They did not show a significant association with available patient information on age at diagnosis, white blood cell count (WBC), CNS disease and relapse incidence, but it is likely that a higher number of T-ALL samples would be required for this analysis.

Figure 2. Association of Rho expression and T-ALL disease characteristics.

Relative expression data for T-ALL samples were log2 transformed and an unsupervised hierarchical clustering algorithm applied (see Materials and Methods). The legend indicates the magnitude and direction of expression changes relative to control T-lymphocyte samples.

In addition to the cluster analysis, the expression of each Rho gene was independentlytested for association with patient information. Interestingly, the expression of RHOQ, RND1 and RHOB was significantly correlated with WBC count (Table 2). As described above, RHOB is highly upregulated in the T-ALL samples. Although RHOQ and RND1 expression in T-ALL was not different overall from normal controls (Fig. 1), this suggests that RHOQ and RND1 expression are increased in a subset of patients with higher WBC. The WBC count could correlate with differences in the migratory properties of leukaemic cells.

Table 2. Association between relative Rho expression in T-ALL and WBC.

The fold expression values for each Rho gene were tested for correlation with white blood cell count at diagnosis (WBC), using the Pearson correlation statistic, R. R values can range from 1, indicating perfect correlation, to −1, indicating perfect inverse correlation.

| gene | Pearson R | P- value |

test summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHOH | 0.14 | 0.440 | ns |

| RHOBTB1 | −0.15 | 0.433 | ns |

| RHOBTB2 | 0.11 | 0.551 | ns |

| RHOA | 0.04 | 0.838 | ns |

| RHOC | 0.25 | 0.172 | ns |

| RAC1 | 0.24 | 0.195 | ns |

| RAC2 | 0.33 | 0.069 | ns |

| RAC3 | 0.25 | 0.178 | ns |

| RHOG | −0.15 | 0.424 | ns |

| CDC42 | 0.24 | 0.186 | ns |

| RHOQ | 0.50 | 0.004 | ** |

| RND1 | 0.40 | 0.050 | * |

| RHOU | −0.02 | 0.912 | ns |

| RHOF | 0.16 | 0.405 | ns |

| RHOB | 0.48 | 0.006 | ** |

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, ns = not significant.

RHOU expression correlates with Notch1 signalling in T-ALL

The NOTCH1 gene is mutated in over 50% of T-ALL cases, leading to dysregulated Notch1 signalling (9) . Mutations in other genes such as FBXW7, a ubiquitin ligase involved in Notch1 turnover, also contribute to constitutive Notch1 signalling in T-ALL (22) . We therefore investigated whether the Rho gene alterations we observed in the T-ALL samples were linked to aberrant Notch1 signalling.

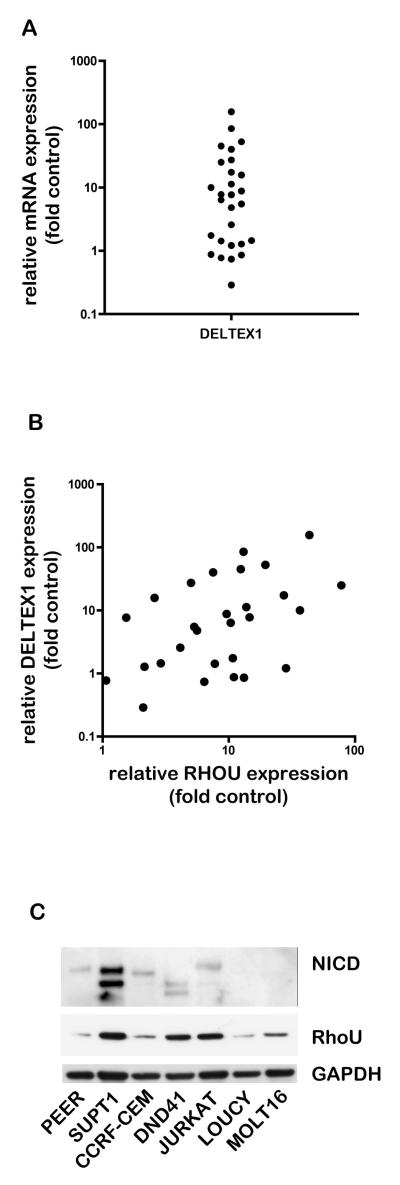

We used the mRNA expression levels of the Notch1 target gene DELTEX1 as a read-out of constitutive Notch1 signalling and screened the T-ALL samples using quantitative PCR (Fig. 3A). DELTEX1 transcript levels were at least two-fold higher than control T cells in 68% of samples, indicating increased Notch1 signalling. This could be due to NOTCH1 mutations or other mutations that affect Notch1 signalling.

Figure 3. Association of RhoU expression with Notch1 signalling in T-ALL patients and cell lines.

A. Deltex-1 mRNA expression in T-ALL and control samples was analysed by quantitative PCR using GAPDH expression as a reference. Deltex-1 mRNA expression in each T-ALL sample was determined relative to the mean expression of the normal control samples using the comparative CT method. Data are expressed as fold expression relative to controls on a logarithmic scale. B. Scatter plot of RHOU and DELTEX1 expression in T-ALL samples. C. Cells from a panel of T-ALL-derived cell lines in growth phase were lysed and then analysed for RhoU protein expression and cleaved Notch1 intracellular domain levels by immunoblotting. A representative blot from three independent experiments is shown.

We determined whether the relative expression levels of any of the Rho genes correlated with the expression of DELTEX1 using a Spearman Rank test (Table 3). RHOU (Fig. 3B) and RAC2 mRNA levels were found to be significantly associated with DELTEX1 in T-ALL samples. Since we had identified RHOU as upregulated in T-ALL, we decided to investigate the relationship between RHOU and Notch1 signalling further.

Table 3. Association between relative Rho gene expression and DELTEX-1 levels in T-ALL.

DELTEX-1 mRNA expression was analysed by quantitative PCR, and GAPDH-normalised dCT values were used to test for correlation between Rho gene and DELTEX-1 expression using a Spearman Rank correlation test;

| gene | Spearman r | P value |

test summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHOH | 0.02 | 0.925 | ns |

| RHOBTB1 | 0.20 | 0.324 | ns |

| RHOBTB2 | 0.30 | 0.122 | ns |

| RHOA | 0.26 | 0.175 | ns |

| RHOC | 0.21 | 0.287 | ns |

| RAC1 | 0.24 | 0.220 | ns |

| RAC2 | 0.46 | 0.014 | * |

| RAC3 | 0.00 | 0.980 | ns |

| RHOG | 0.29 | 0.137 | ns |

| CDC42 | 0.34 | 0.073 | ns |

| RHOQ | 0.29 | 0.137 | ns |

| RND1 | 0.25 | 0.260 | ns |

| RHOU | 0.45 | 0.016 | * |

| RHOF | 0.27 | 0.163 | ns |

| RHOV | −0.31 | 0.111 | ns |

| RND2 | −0.15 | 0.443 | ns |

| RND3 | 0.10 | 0.605 | ns |

P < 0.05, ns = not significant.

A number of T-lymphoblastic cell lines have been derived from T-ALL patients. Several have mutations that lead to constitutive Notch1 signalling, whereas others have normal ligand-dependent Notch signalling (22) . We used a panel of T-ALL cell lines to investigate whether there was an association between Notch1 signalling status and RhoU protein expression. In accordance with published data, we detected cleaved Notch1 in PEER, SUPT1, CCRF-CEM, DND41 and Jurkat lines but not in LOUCY and MOLT16 lines, which do not have Notch1 mutations (Fig. 3C)(22) . The different sizes of NICD detected in the cell lines reflect different sites of mutation in Notch1 and/or FBW7, a ubiquitin ligase involved in Notch1 degradation (22) . RhoU protein was expressed in all the cell lines, indicating that RhoU expression is not strictly dependent on oncogenic Notch1 activation. However, it was highest in SUPT1, DND41 and JURKAT cells, which have cleaved Notch1.

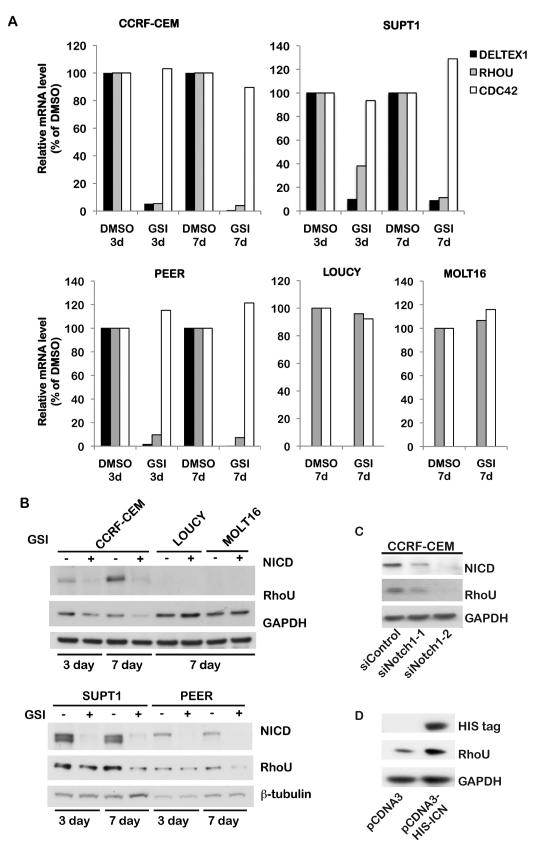

RhoU expression is regulated by Notch1 signalling

To determine if RhoU expression is influenced by Notch1 signalling, we first utilized the γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) compound E to block the generation of NICD (23,24) . T-ALL cell lines with activating NOTCH1 mutations (CCRF-CEM, SUPT1 and PEER) and lines with wild-type NOTCH1 (LOUCY and MOLT16) were treated with GSI or DMSO (vehicle control) for three and seven days to allow time for gene expression changes to occur. RHOU mRNA levels in response to the treatment were determined by qPCR (Fig. 4A). DELTEX1 mRNA levels were quantified to confirm Notch1 signalling inhibition, and CDC42 mRNA was used as an additional control since its expression was not correlated with DELTEX1 (Table 3). As expected, GSI treatment led to a dramatic reduction in the levels of DELTEX1 mRNA in all three NOTCH1 mutant lines. GSI treatment resulted in a reduction of RHOU mRNA in these T-ALL lines, whereas CDC42 was unaffected (Fig. 4A). In contrast, in the NOTCH1 wild-type lines, RHOU expression was unaffected by GSI treatment. We could not detect DELTEX1 mRNA well enough for quantification in LOUCY and MOLT16 lines, consistent with the absence of constitutive Notch1 signalling (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Notch1 regulates RhoU expression.

A. T-ALL cell lines were treated with GSI or DMSO (vehicle) for 3 or 7 days. RNA was extracted and analysed by quantitative PCR to determine relative mRNA expression levels of DELTEX1, RHOU and CDC42, with GAPDH as a reference. Fold expression changes were determined relative to expression in DMSO-treated cells using the comparative CT method. B. Cells treated as in A were lysed and protein levels of the cleaved Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) and RhoU were determined by immunoblotting. Blots were probed for GAPDH or ß-tubulin as loading controls. Representative data from 3 independent experiments are shown. C. CCRF-CEM cells were transfected with control siRNA or two different siRNAs (1, 2) targeting Notch1. Cells were lysed after 72 hours and analysed by immunoblotting for levels of NICD, RhoU, and GADPH as a loading control. D. A construct encoding His-tagged NICD was transfected into Cos7 cells. After 48 h, cells were solubilised in protein sample buffer and His-tag and RhoU were detected by immunoblotting. GADPH was used as a loading control. A representative blot from 3 independent experiments is shown.

We next analyzed the dependence of RhoU protein expression on Notch1 signalling. GSI treatment resulted in a reduction of NICD levels at three and seven days of treatment in the three NOTCH1 mutant lines, showing that the GSI treatment was inhibiting Notch1 cleavage. There was a progressive reduction in RhoU protein with GSI treatment in these lines (Fig. 4B), whereas Rac2 levels were not affected (Suppl Fig. 2A). In contrast, RhoU protein levels in the lines with wild-type NOTCH1 (LOUCY, MOLT16) were unaffected by GSI treatment. As expected, NICD was not detected in these lines (Fig. 4B).

γ-secretase cleaves a number of proteins in addition to Notch1 (25) , and thus we tested whether the effects of GSI on RhoU were also observed with direct Notch1 inhibition. Two different Notch1 siRNAs strongly reduced RhoU protein levels in CCRF-CEM cells (Fig. 4C). To determine whether Notch1 signalling alone could induce RhoU expression, the NICD was expressed in COS7 cells. NICD expression led to an increase in RhoU protein levels (Fig. 4D). Together, these data show that Notch1 signalling positively regulates the expression of RhoU.

RhoU regulates T-ALL cell polarization, migration and adhesion

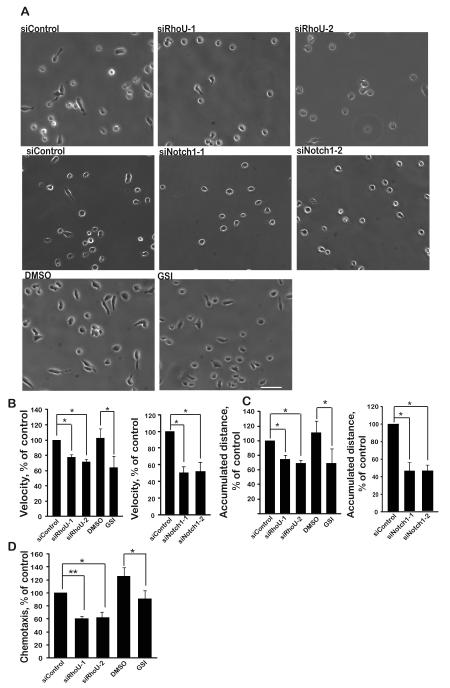

Since Rho GTPases are well known to regulate cell migration (26) , we investigated whether RhoU affected the migration of T-ALL cells. We chose CCRF-CEM cells since they have mutated NOTCH1, and are well characterized for their migration behaviour (21,27,28) . RhoU expression was downregulated in CCRF-CEM cells by transfection with two different siRNAs (Suppl Fig. 2B). RhoU-depleted cells had a rounder morphology and migrated more slowly on fibronectin than control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 5A, B). Similarly, GSI-treated cells and Notch1-depleted cells were more rounded and migrated more slowly than control cells (Fig. 5A, B). RhoU- and Notch1-depleted cells and GSI-treated cells also showed reduced total migration distance over 1 h (Fig. 5C) and RhoU and GSI affected chemotaxis towards CXCL12 in transwells (Fig. 5D). RhoU or Notch1 depletion did not detectably affect cell number or viability compared to siControl-transfected cells, as determined with a CASY cell counter.

Figure 5. RhoU regulates T-ALL cell morphology and migration.

CCRF-CEM cells were transfected with control siRNA, two different siRNAs (1, 2) targeting RhoU or Notch1 or treated for 7 days with 100 nM GSI or DMSO (vehicle). A. Cells were added onto fibronectin-coated wells and stimulated with 1 ng/ml CXCL12 for 30 min. Phase-contrast time-lapse images were collected every 1 min for 1 h. Images shown are at 0 min. Scale bar 50 μm. Representative of 3 independent experiments. Relative velocity (B) and accumulated distance (C) was determined by tracking 60 cells in each of 3 independent experiments. (D) Cells were added to fibronectin-coated transwells containing 30 ng/ml CXC12 in the lower chamber. Cells that had migrated into the bottom of the well were counted after 1 h using a Casy Counter. Data shown are mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *p <0.05, **p <0.01; two-tailed paired t-test.

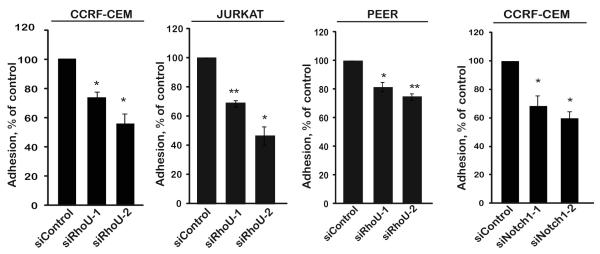

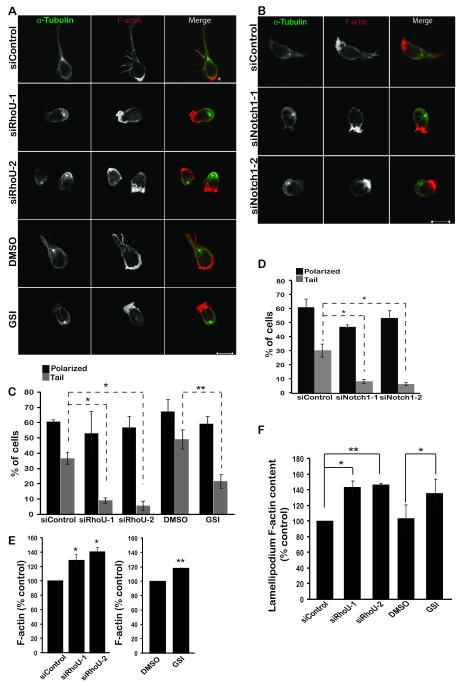

The rounded phenotype of RhoU-depleted and Notch1-inhibited cells suggested they might have an adhesion defect. Indeed, depletion of RhoU or Notch1 or treatment with GSI reduced adhesion CCRF-CEM cells to fibronectin (Fig. 6, Suppl Fig. 2C). Similarly, RhoU depletion reduced adhesion of two other T-ALL cell lines, JURKAT and PEER (Fig. 6A, Suppl Fig. 2B), indicating that the effect of RhoU is not cell type-specific. Next we investigated whether RhoU depletion or Notch1 inhibition altered migratory polarity by staining for F-actin and microtubules (27) . RhoU or Notch1-depleted cells and GSI-treated cells still had a single F-actin-rich lamellipodium at the front and the microtubule-organising center was behind the nucleus, but there was a strong reduction in the number of cells with tails compared to control cells (Fig. 7A-D). Interestingly, the total level of F-actin in RhoU-depleted or GSI-treated cells was increased (Fig. 7E), and the level of F-actin in lamellipodia also increased (Fig. 7F). RhoU depletion therefore affects T-ALL cell morphology and migration, and these effects can be reproduced by GSI-mediated inhibition of Notch1 signalling.

Figure 6. RhoU and Notch1 regulate T-ALL cell adhesion.

CCRF-CEM, JURKAT or PEER cells were transfected with control siRNA or two different siRNAs (1,2) targeting RhoU or Notch1. After 72 hours, cells were labelled with CellTracker dye CMFDA and incubated on fibronectin-coated wells. Adhesion was determined after 30 min. Data shown are the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *p <0.05, **p <0.01; two-tailed paired t-test.

Figure 7. RhoU regulates polarity.

CCRF-CEM cells were transfected with control siRNA, two different siRNAs targeting RhoU or Notch1 (1, 2) or treated for 7 days with 100 nM GSI or DMSO (vehicle). A, B. Cells were plated onto fibronectin-coated wells and stimulated for 30 min with 1 ng/ml CXCL12. Samples were then fixed and stained for F-actin and α-tubulin and imaged by confocal microscopy. Arrow indicates microtubule-organizing center (MTOC); * indicates high F-actin staining in the lamellipodium. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, D. The % of polarized cells and cells with tails was quantified as described in Materials and Methods, by counting 100 cells in each of 3 independent experiments. E. Cells were fixed, permeabilized and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labelled phalloidin and analyzed by flow cytometry. F. F-actin level at the leading edge was quantified using ImageJ software. Data shown are the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *p <0.05, **p <0.01; two-tailed paired t-test.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of T-ALL suggests a significant deregulation of cell migration and tissue infiltration. Large numbers of T-ALL cells accumulate in the peripheral blood and tissues, with frequent metastasis to the CNS. We show that 8 of the 20 human Rho GTPases are upregulated in T-ALL compared to normal T cells. We find that expression of the atypical Rho family member RHOU is regulated by Notch1 and demonstrate that RhoU is required for optimal adhesion, migration and chemotaxis of T-ALL cells. This indicates that RhoU could contribute to T-ALL progression in NOTCH1 mutant T-ALL patients.

RhoU and RhoV form a subfamily of Rho GTPases that have a high intrinsic guanine nucleotide exchange activity and are thus believed to be predominantly GTP-bound (16) . RhoU (also known as Wrch1) and RhoV (also known as Chp) have been implicated in migration in several cell types but have not previously been studied in leukocytes. For example, they have been shown to stimulate lamellipodial or filopodial extension and/or an increase in integrin-based focal adhesions (29-31) . In osteoclasts, RhoU is found in podosomes and influences integrin signaling (32) , and RhoU is required for neural crest cell migration in vivo (33) . Our data also indicate that RhoU is involved in regulating T-ALL cell adhesion. RhoU-depleted T-ALL cells had a more rounded phenotype and lacked uropods/tails. RhoU depletion also resulted in reduced migration and CXCL12-stimulated chemotaxis. Loss of the uropod and reduced migration are consistent with a decrease in cell adhesion. So far it is not clear how RhoU or RhoV affect cell adhesion, although RhoV was shown to bind to and cause the degradation of the Rac/Cdc42 effector PAK1, which is implicated in focal adhesion turnover (34,35) . The increased expression of RhoU and RhoV in T-ALL samples compared to normal T cells could therefore affect their attachment in the bone marrow and thymus, as well as entry into and out of the peripheral circulation and tissues.

The increased expression of Rho GTPases that we observe in T-ALL samples is likely to reflect gene expression changes due to T-ALL genetic alterations (2,36) . Indeed, we show that RHOU expression is regulated by Notch1. RHOU was also among the most downregulated genes in two T-ALL cell lines treated with SAHM1, a new type of Notch inhibitor that prevents formation of the active NICD/CSL transcription factor complex (37) . Importantly, similar morphological and migratory phenotypes were induced in T-ALL cells by RhoU depletion and by inhibiting Notch1 activation with GSI treatment, indicating that RHOU is the predominant target of Notch1 involved in regulating cell migration. Interestingly, RHOU was initially identified as a Wnt-regulated gene (38) , and Wnt signaling plays an important role in T cell development (39) . In the future it will be important to test whether other T-ALL-associated transcription factors affect the expression of Rho GTPases upregulated in T-ALL.

In addition to RHOU and RHOV, we found that 4 other atypical Rho GTPases are upregulated in T-ALL: RHOH, RHOBTB1, RND2 and RND3. RHOH is mutated through chromosomal translocations or somatic hypermutation in a number of B-cell-derived leukaemias and lymphomas, but has not previously been implicated in T-cell-derived leukemias (40) . However, it does regulate T-cell receptor signaling and T-cell migration (13,41) , and could thereby affect T-ALL progression. So far little is known about RHOBTB1 in cancer. It has been proposed as a candidate tumour suppressor in head and neck cancer, but the mechanistic basis for this function is unknown (42) . There is no evidence as yet that RhoBTB1 is involved in cytoskeletal regulation (29) ; instead, the RhoBTB proteins have been implicated in cullin3-based ubiquitination as well as transcription regulation via BTB domain-dependent interactions (29,43) . It will therefore be important to determine how RhoBTB1 contributes to T-ALL. In contrast to RhoBTB1, Rnd2 and Rnd3 affect the actin cytoskeleton and affect cell migration in a variety of cultured cell lines (29,44) , although their function has not so far been studied in lymphocytes.

RHOB was consistently highly upregulated in T-ALL, whereas the fold-increase in RHOA expression was less. RHOA overexpression has been reported in a variety of tumor types, including colon, breast, testicular germ cell and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (45) . On the other hand, RhoB, which is involved in actin organization and membrane receptor trafficking (46) , has been primarily reported as a tumor suppressor based on expression analysis in solid tumors, although how it acts is not completely understood (17,47) . RHOB expression is rapidly induced in response to a variety of stimuli including growth factor stimulation and genotoxic stress (47) , and thus it is possible that a specific stimulus in T-ALL cells induces high RHOB levels.

In addition to our results on Rho GTPases, some T-ALL-related gene expression analysis studies have identified other potential regulators of cell migration. For example, the tetraspanin TALLA-1 (tetraspanin-7) is a target of the transcription factor TAL1 (48) , which is frequently overexpressed in T-ALL (49) . Several tetraspanins affect integrin-mediated processes such as adhesion, migration and invasion, but the function of TALLA-1 is not known (50) . TAL1 target genes identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation included some regulators of the cytoskeleton (23) . Overexpression of NICD altered the expression of chemokines, cell adhesion molecules and metalloproteases (11) . In particular, the chemokine receptor CCR7 was upregulated and caused targeting of leukaemic blast cells to the brain endothelium. Together with our data, these results indicate that genes regulating cell adhesion, migration and invasion are modulated in T-ALL and could contribute to disease pathophysiology.

Materials & Methods

T-ALL patient samples and normal T-lymphocyte isolation

The primary childhood leukaemia samples used in this study were provided by the Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research Childhood Leukaemia Cell Bank (UK), in accordance with the requirements of the Childhood Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) and the Cell Bank Steering Committee. Frozen samples (mononuclear bone marrow cells or peripheral blood) obtained from 30 T-ALL patients at diagnosis were used. T-ALL samples are generally accepted to be more than 90% leukaemic blasts. T-lymphocytes were isolated from buffy coats of 5 healthy blood donors. Mononuclear cells were separated by density gradient according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Lymphoprep, Axis-Shield). Cells were then treated with 0.5% phytohaemagglutinin (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) in RPMI medium (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) containing 10% foetal calf serum for 48 h, followed by culture for 10 days in 10 U/ml human IL-2 (Roche Diagnostics, Burgess Hill, UK). The T-lymphocyte populations obtained were >90% pure, defined by CD4+ or CD8+ single positive populations measured by flow cytometry with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies (BD Bioscences, Oxford, UK).

Cell culture and GSI treatment

CCRF-CEM and JURKAT cells were purchased from ATCC (LGL Promochem, Middlesex, UK). PEER, SUPT1, MOLT16 and LOUCY T-ALL cell lines were from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). Cell lines were cultured in Dulbeco’s RPMI containing 2 mM glutamine and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). COS7 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). GSI (Compound E, Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK) was solubilised in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO). Cell lines were resuspended in medium containing 100 nM GSI or an equal volume of DMSO and cultured for the indicated times. For 7 day treatments, cells were re-treated at a lower cell density in fresh GSI-containing medium after 3 or 4 days.

Transfection

Cells (5 × 105) were transfected by nucleofection (Amaxa Biosystems Nucleofection System) with 1.2 μM siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) in 100 μl of Nucleofection reagent (kit C, Lonza Biologics, Slough, UK). siRNA sequences were RhoU-1: CAGAGAAGAUGUCAAAGUC; RhoU-2: AAGCAGGACUCCAGAUAAAUU; Notch1-1: GAACGGGGCUAACAAAGAU; Notch1-2: GCAAGGACCACUUCAGCGA. siControl was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (D-001810-02-20, Lafayette, USA). Cells were used for experiments 48 to 72 h after siRNA transfection.

pcDNA3 encoding HIS-tagged Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) or vector alone was transfected into COS7 cells by electroporation. Cells were detached from the plate and washed twice in electroporation buffer (10 mM KCl, 10 mM K2PO4/KHPO4 pH 7.6, 25 mM Hepes pH 7.6, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Ficoll 400). After resuspending in 250 μl of electroporation buffer cells were mixed with 5 μg DNA in a 0.4 cm electroporation cuvette and left on ice for 10 min. Samples were then electroporated at 250 V, 975 μF and left again on ice for 5 min and at room temperature for other 5 min. Cells were finally plated in 10 cm dish and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After 48 h, cells were solubilised in protein sample buffer, and protein expression was analysed by immunoblotting.

Sample preparation and real-time SYBR-Green PCR

RNA from T-ALL samples and control T-lymphocytes was extracted by the Trizol method (Invitrogen), and treated with DNase (RNase-free, Ambion) to remove genomic DNA. RNA concentration was determined, and purity was checked by measuring the A260/A280 ratio. cDNA was prepared from identical amounts of RNA template with Superscript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen).

Relative mRNA expression of Rho genes was determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays, using SYBR-Green detection chemistry (PCR mastermix from Primer Design, Southampton, UK) and the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Primers used for each gene are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Wherever possible, primers were designed either across different exons or across exon-exon boundaries to avoid detection of genomic sequences. Each gene assay was validated for amplification efficiency between 90 and 110% by serial template dilutions, and for specificity by melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. The expression analysis for each gene was carried out in a 96 well format, comparing all 5 control samples to batches of 6 or 7 T-ALL samples, and for each sample assaying a Rho gene in parallel with GAPDH as a reference. CT values of controls could therefore be used to correct for plate-to-plate variations.

Statistical analyses

For T-ALL-associated expression changes, mean CT values for each sample were first normalised to GAPDH CT values (expressed as dCT). Differential gene expression between control and T-ALL samples was determined by the Mann-Whitney U test for medians of dCT values. For clustering analyses, the comparative CT method (51) (using the average CT of the controls) was used to determine relative fold expression changes for Rho genes in each T-ALL sample. Cluster analysis software (Cluster 3.0)(52) and Java Treeview (53) ) were used to generate a heat-map of the fold changes as well as carry out unsupervised hierarchical clustering of genes and T-ALL samples. Complete linkage clustering algorithm was applied, using Pearson correlation as the similarity metric. Characteristics of grouped or clustered T-ALL patients were compared by Mann-Whitney U test for medians or the Fisher’s Exact test for associations, in two-tailed tests and considered significant if P < 0.05. Statistical tests were carried out using Graphpad Prism 5 software.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed directly in Laemmli sample buffer and immediately heated to at least 90°C for 10 min. Proteins were resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membrane, and detected by immunoblotting. The following antibodies were used: Cleaved Notch1 intracellular domain (Val1744, Cell Signaling, Hitchin, UK), RhoU (Wrch1 ab80315, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), ß-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), HIS-tag (Cell Signaling), GAPDH and Rac2 (Millipore).

Immunofluorescence

Glass coverslips were coated with 10 μg/ml fibronectin at 4°C overnight and blocked in 2.5% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h. 2×105 cells were added to each coverslip and incubated at 37°C with 1ng/ml of CXCL12 (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) for 30 min. Subsequently, samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton-X-100. Following 2 washes in PBS cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin (A22283, Invitrogen) and FITC-labeled anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma) for 1 h. Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides using Dako (Ely, UK) anti-fade mounting medium. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM500 confocal microscope (Zeiss). F-actin content was measured using ImageJ software. Each experimental condition was done with triplicate coverslips, counting 100 cells on each. Data was pooled from three independent experiments. Polarized cells were defined as having F-actin localized to one side of the cell, defined as the leading edge, and the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) localized at the other side of the nucleus with respect to the leading edge. Elongated tails on cells were defined as a narrow protrusion at the opposite side to the leading edge, at least the length of the cell body.

Timelapse microscopy

siRNA-transfected or DMSO/GSI-treated CCRF-CEM cells were counted (Innovatis CASY cell counter, Roche Applied Bioscience, Burgess Hill, UK), and 2×105 were added to each well of a fibronectin-coated 8-well culture slides (BD Falcon, Oxford, UK). After 30 min, wells were washed three times with complete culture medium to remove loosely attached and non-viable cells, then stimulated with 1 ng/ml of CXCL12. Bright field phase-contrast images were collected every minute for 1 h on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope with a charge-coupled device camera (ORCA, Hamamatsu Photonics) using Metamorph software. Cells were tracked, and velocities and distance migrated calculated using Image J.

Adhesion assay

96-well plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 10 μg/ml fibronectin. Cells were resuspended in PBS at 106 cells/ml and incubated at 37°C for 15 min with 2 μM CellTracker Green CMFDA (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Cells were then resuspended in warm media and 105 cells/well (each sample in triplicate) were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After washes with PBS the plate was read on a Fusion-αFP plate reader (PerkinElmer, Cambridge, UK) at 485 nm excitation and 525-535 nm emission.

Flow cytometry

T-ALL cells (2×105) were centrifuged and washed with PBS. Cells were fixed at room temperature for 10 min with 4% PFA and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Samples were then incubated with 0.2 μg/ml Alexa488-labelled phalloidin and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACS Calibur machine using FlowJo program.

Supplementary Material

RNA was extracted from 30 T-ALL blast samples and normal T-lymphocytes from 5 peripheral blood samples of healthy donors. mRNA expression of each Rho gene was measured by quantitative PCR, using GAPDH expression as a reference. The CT value for each Rho gene is shown relative to the CT value for GADPH in each sample.

(A) CCRF-CEM, SUPT1 and PEER cells were treated with 100 nM GSI or DMSO (vehicle) for 7 days. Cleaved Notch1 intracellular domain and Rac2 were detected by western blotting. (B) CCRF-CEM, JURKAT and PEER cells were transfected with control siRNA and two different siRNAs (1, 2) targeting RhoU. The level of RhoU was determined 3 days after transfection by immunoblotting. GADPH was used as a loading control. (C) CCRF-CEM cells were treated with 100 nM GSI or DMSO for 7 days. Cells were then labelled with cell tracker dye CMFDA and incubated on fibronectin-coated wells. Adhesion was determined after 30 min. Data shown are the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *p <0.05, **p <0.01; two-tailed paired t-test.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research UK, Cancer Research UK, and King’s College London British Heart Foundation Centre of Excellence. E.I. was supported by the Department of Health via National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre Award to Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. We are grateful to Sarah Heasman for scientific discussion and guidance, Ritu Garg and Katrina Soderquest for technical assistance, Katherine Lawler for advice on statistical analysis, and Matthew Arno and Estibaliz Aldecoa-otalora Astarloa for assistance and advice on qPCR.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare they do not have any conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Pieters R, Carroll WL. Biology and treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aifantis I, Raetz E, Buonamici S. Molecular pathogenesis of T-cell leukaemia and lymphoma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:380–390. doi: 10.1038/nri2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crazzolara R, Kreczy A, Mann G, Heitger A, Eibl G, Fink FM, et al. High expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 predicts extramedullary organ infiltration in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:545–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhojwani D, Howard SC, Pui CH. High-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(Suppl 3):S222–230. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.s.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JPt, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Grotel M, Meijerink JP, van Wering ER, Langerak AW, Beverloo HB, Buijs-Gladdines JG, et al. Prognostic significance of molecular-cytogenetic abnormalities in pediatric T-ALL is not explained by immunophenotypic differences. Leukemia. 2008;22:124–131. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayday AC, Pennington DJ. Key factors in the organized chaos of early T cell development. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:137–144. doi: 10.1038/ni1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vicente R, Swainson L, Marty-Gres S, De Barros SC, Kinet S, Zimmermann VS, et al. Molecular and cellular basis of T cell lineage commitment. Semin Immunol. 2010;22:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Pear WS. Notch signalling in T-cell lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma and other haematological malignancies. J Pathol. 2011;223:262–273. doi: 10.1002/path.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrando AA. The role of NOTCH1 signaling in T-ALL. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:353–361. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buonamici S, Trimarchi T, Ruocco MG, Reavie L, Cathelin S, Mar BG, et al. CCR7 signalling as an essential regulator of CNS infiltration in T-cell leukaemia. Nature. 2009;459:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/nature08020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Hennik PB, Hordijk PL. Rho GTPases in hematopoietic cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1440–1455. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tybulewicz VL, Henderson RB. Rho family GTPases and their regulators in lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:630–644. doi: 10.1038/nri2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boureux A, Vignal E, Faure S, Fort P. Evolution of the Rho family of ras-like GTPases in eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:203–216. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang FK, Sato N, Kobayashi-Simorowski N, Yoshihara T, Meth JL, Hamaguchi M. DBC2 is essential for transporting vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aspenstrom P, Ruusala A, Pacholsky D. Taking Rho GTPases to the next level: the cellular functions of atypical Rho GTPases. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3673–3679. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vega FM, Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases in cancer cell biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2093–2101. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellenbroek SI, Collard JG. Rho GTPases: functions and association with cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:657–672. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Symons M, Segall JE. Rac and Rho driving tumor invasion: who’s at the wheel? Genome Biol. 2009;10:213. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parri M, Chiarugi P. Rac and Rho GTPases in cancer cell motility control. Cell Commun Signal. 2010;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heasman SJ, Carlin LM, Cox S, Ng T, Ridley AJ. Coordinated RhoA signaling at the leading edge and uropod is required for T cell transendothelial migration. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:553–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Neil J, Grim J, Strack P, Rao S, Tibbitts D, Winter C, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palomero T, Odom DT, O’Neil J, Ferrando AA, Margolin A, Neuberg DS, et al. Transcriptional regulatory networks downstream of TAL1/SCL in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:986–992. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palomero T, Sulis ML, Cortina M, Real PJ, Barnes K, Ciofani M, et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat Med. 2007;13:1203–1210. doi: 10.1038/nm1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfe MS. γ-Secretase in biology and medicine. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:690–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takesono A, Heasman SJ, Wojciak-Stothard B, Garg R, Ridley AJ. Microtubules regulate migratory polarity through Rho/ROCK signaling in T cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Infante E, Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. Statins inhibit T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell adhesion and migration through Rap1b. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:577–586. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0810441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aspenstrom P, Fransson A, Saras J. Rho GTPases have diverse effects on the organization of the actin filament system. Biochem J. 2004;377:327–337. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuang YY, Valster A, Coniglio SJ, Backer JM, Symons M. The atypical Rho family GTPase Wrch-1 regulates focal adhesion formation and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1927–1934. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aronheim A, Broder YC, Cohen A, Fritsch A, Belisle B, Abo A. Chp, a homologue of the GTPase Cdc42Hs, activates the JNK pathway and is implicated in reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1125–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brazier H, Pawlak G, Vives V, Blangy A. The Rho GTPase Wrch1 regulates osteoclast precursor adhesion and migration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1391–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fort P, Guemar L, Vignal E, Morin N, Notarnicola C, Barbara Pde S, et al. Activity of the RhoU/Wrch1 GTPase is critical for cranial neural crest cell migration. Dev Biol. 2011;350:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubsman M Weisz, Volinsky N, Manser E, Yablonski D, Aronheim A. Autophosphorylation-dependent degradation of Pak1, triggered by the Rho-family GTPase, Chp. Biochem J. 2007;404:487–497. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arias-Romero LE, Chernoff J. A tale of two Paks. Biol Cell. 2008;100:97–108. doi: 10.1042/BC20070109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrando AA, Neuberg DS, Staunton J, Loh ML, Huard C, Raimondi SC, et al. Gene expression signatures define novel oncogenic pathways in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, et al. Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex. Nature. 2009;462:182–188. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tao W, Pennica D, Xu L, Kalejta RF, Levine AJ. Wrch-1, a novel member of the Rho gene family that is regulated by Wnt-1. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1796–1807. doi: 10.1101/gad.894301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weerkamp F, van Dongen JJ, Staal FJ. Notch and Wnt signaling in T-lymphocyte development and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1197–1205. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fueller F, Kubatzky KF. The small GTPase RhoH is an atypical regulator of haematopoietic cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2008;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H, Zeng X, Fan Z, Lim B. RhoH plays distinct roles in T-cell migrations induced by different doses of SDF1α. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1022–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berthold J, Schenkova K, Rivero F. Rho GTPases of the RhoBTB subfamily and tumorigenesis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:285–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berthold J, Schenkova K, Ramos S, Miura Y, Furukawa M, Aspenstrom P, et al. Characterization of RhoBTB-dependent Cul3 ubiquitin ligase complexes--evidence for an autoregulatory mechanism. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3453–3465. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riou P, Villalonga P, Ridley AJ. Rnd proteins: multifunctional regulators of the cytoskeleton and cell cycle progression. Bioessays. 2010;32:986–992. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez del Pulgar T, Benitah SA, Valeron PF, Espina C, Lacal JC. Rho GTPase expression in tumourigenesis: evidence for a significant link. Bioessays. 2005;27:602–613. doi: 10.1002/bies.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and actin dynamics in membrane protrusions and vesicle trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang M, Prendergast GC. RhoB in cancer suppression. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:213–218. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ono Y, Fukuhara N, Yoshie O. Transcriptional activity of TAL1 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) requires RBTN1 or -2 and induces TALLA1, a highly specific tumor marker of T-ALL. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4576–4581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graux C, Cools J, Michaux L, Vandenberghe P, Hagemeijer A. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: from thymocyte to lymphoblast. Leukemia. 2006;20:1496–1510. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanez-Mo M, Barreiro O, Gordon-Alonso M, Sala-Valdes M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Tetraspanin-enriched microdomains: a functional unit in cell plasma membranes. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview--extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3246–3248. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

RNA was extracted from 30 T-ALL blast samples and normal T-lymphocytes from 5 peripheral blood samples of healthy donors. mRNA expression of each Rho gene was measured by quantitative PCR, using GAPDH expression as a reference. The CT value for each Rho gene is shown relative to the CT value for GADPH in each sample.

(A) CCRF-CEM, SUPT1 and PEER cells were treated with 100 nM GSI or DMSO (vehicle) for 7 days. Cleaved Notch1 intracellular domain and Rac2 were detected by western blotting. (B) CCRF-CEM, JURKAT and PEER cells were transfected with control siRNA and two different siRNAs (1, 2) targeting RhoU. The level of RhoU was determined 3 days after transfection by immunoblotting. GADPH was used as a loading control. (C) CCRF-CEM cells were treated with 100 nM GSI or DMSO for 7 days. Cells were then labelled with cell tracker dye CMFDA and incubated on fibronectin-coated wells. Adhesion was determined after 30 min. Data shown are the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SEM. *p <0.05, **p <0.01; two-tailed paired t-test.